He would wake up running. Slam into the wall. Flail about the closet hangers. Show up at work the next morning with his face bruised or cut.

He woke – Uganda almost fifteen years away, but the bodies still there. The mutilated forms of his companions. He packed the pieces into bags. Loaded them onto trucks to be dumped into the crocodile waters. Returned to scrub his companions’ blood from the barracks. Watched them hacked to death again.

He couldn’t sleep. He washed dishes, cleaned house, read – anything to stave off the nightmares. He dozed two, maybe three, hours a night, trained himself to survive in a constant sleep deprived state. The less he slept, the more secure he felt. He passed numbly through the days.

The nightmares tyrannized his life. They almost ended it. Had he run through the screen door instead of into the wall, he would have fallen three flights. At times, he would have preferred it to watching the murders, bagging the bodies again.

By accident, he found the Center for Victims of Torture. The first time he walked into the house on East River Road in Minneapolis, a dozen years ago, he sensed a foreign calm. He talked to a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, and a medical doctor. His appointments over, he stayed another two hours, simply sitting in the lounges comfort. He went home and slept for three days.

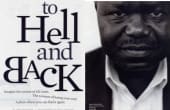

Richard Oketch woke to a new life, one that he would slowly, gradually assemble. “What the center did was remove this veil,” Oketch says today. “They pushed back into my body the soul that wasn’t there.”

THAT’S WHAT THE Center for Victims of Torture has been doing for twenty years. Torture—as the blatant Abu Ghraib prison photos reminded us—demeans and destroys a person’s sense of self. The experience occupies the psyche long after the physical attacks stop. For those who’ve had their self-esteem, dignity, trust—virtually their life—stomped, smacked, carved, shocked, burned, raped, mutilated, or shouted out of them, CVT has provided comfort and healing. The center, with its innovative and unique multidisciplinary approach, has become a world leader in treating the trauma left in tortures wake.

ON A SEPTEMBER after noon, Richard Oketch relaxes at the CVT. Sunlight grazes the crisp blue sky outside the window. Oketch, fifty-three, is neatly attired in a checked, tan and yellow African-style suit. He speaks somberly of the dark days in Uganda almost thirty years ago. But occasionally his lyrical voice lights on a happy thought and dimples crater his rounded cheeks. He can talk now— even smile—about life. Watching him spontaneously act out a scene from a British comedy—the routine ending in that large smile and an elegant flourish of his hands—you would have trouble picturing him leaping out of bed in a rush of sweat. Until he told you his story.

Remember Idi Amin, the “Butcher of Uganda”? Oketch’s father was a county commissioner in the government Amin ousted; his uncle was a member of parliament. Amin’s thugs killed Oketch’s uncle. They killed his cousins. They abducted his sister and her boyfriend. They arrested and tortured Oketch when he tried to find out what happened to his sister. He managed to escape after two months with the help of high school classmates involved in the secret service.

The second time, he was stopped at a roadblock and taken because of his name and because he had a beard— only guerrillas wore beards, the government figured. Everyone was a suspect at the time. This detention lasted almost four months, until former classmates again helped him escape by getting him reassigned to a less-secure detention center.

The third time was the worst. The soldiers nabbed him in a morning raid and took him to Makindye, a military barracks converted into an underground detention center. There, drunken soldiers, like boys pulling the wings off flies, preyed upon the prisoners for sport. They forced the prisoners to drink themselves into stupors. They beat them with canes. They cut them with bayonets. They slit their throats and sliced their bodies with machetes. They forced Oketch and others to clean up the mess.

It was the stuff of nightmares.

“Seeing people killed is worse than being beaten up yourself,” Oketch says. “The pain of that sight, seeing someone killed in front of you . . . that pain lives forever. If you survive that place, you don’t feel comfortable the rest of your life.” He clenches his lips, brings his hand to his mouth. His eyes look away.

Once again, a sympathetic classmate aided his escape, and this time, Oketch fled Uganda. He made his way from refugee camps in Kenya and Zambia to Ireland, where he tried to dissolve the memories with alcohol. He stopped drinking when he headed to the United States and enrolled in graduate school to study educational psychology. After completing his master’s degree, he found a special education job in the St. Paul school system and moved to Minnesota in 1989.

Oketch had sought help twice before, while living in Ohio and Iowa, but the medical staffs did not understand the nature of his problems. They attributed his nightmares and other symptoms to drug or alcohol use, despite his protestations that he had stopped drinking and did not use drugs. They prescribed meds and referred him to psychiatric centers. He had given up on anyone being able to understand.

In Minnesota; he felt isolated, the way torture survivors often do. He avoided groups. He didn’t trust anyone. He craved security. Work offered it. He often stayed late, until five or six in the evening, well after everyone else had left the school building. He feared returning home to the scene of his nightmares. In his car, alone and comfortable, he felt safe. He sometimes spaced out and kept driving, imbibing the tranquility. One time he wound up in Madison, more than 200 miles beyond his St. Paul apartment.

This might have continued indefinitely had not a volunteer at the University of Minnesota’s Human Rights Center mentioned CVT to Oketch after seeing him flinch at the casual mention of Idi Amin. “If you don’t get treatment, I don’t know where these things will take you,” he said.

THE CENTER FOR Victims of Torture started with a son challenging his father to make the world a better place. Not an uncommon challenge, except in this case the son was Rudy Perpich Jr., then an Amnesty International volunteer at Stanford Law School, and his father was governor of Minnesota. Rudy Perpich Sr. promised he would? use his position to do what he could. Tapping local experts in human rights issues, he embraced their suggestion to establish the first treatment center for victims of torture in the United States. At the time, 1985, only Canada and Denmark had similar centers. There are now 34 centers in the United States and 177 worldwide.

An estimated 500,000 torture survivors reside in the United States. More than 30,000 of them live in Minnesota, according to a recent study. You wouldn’t know who they are simply by looking at them. They are men and women. They are children and adults. They are black and white. They are from all over the world—Amnesty International reports incidences of torture and mistreatment in more than 150 countries.

More than likely, they were professionals or community leaders back home. Of the more than 1,350 clients served by CVT in the Twin Cities, more than half were students or professionals in their native countries, as was Oketch, who taught hearing-impaired children at an elementary school in Uganda; more than 50 percent have some college or vocational education; more than a third are under thirty years of age; 60 per cent are between the ages of twenty and forty. They are divided almost evenly between men and women, and almost all female clients have been sexually tortured; a study of Somali and Ethiopian refugees in Minnesota published in the American Journal of Public Health in April 2004 found women were tortured as often as men in some communities, more often in others. CVT clients were detained on average six times before they managed to escape and seek refuge. A quarter of them were first tortured as children, often to intimidate or punish their parents. They have come from more than sixty countries. Currently, the overwhelming majority are from West African countries such as Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Cameroon.

In the twenty years since its inception, CVT has established itself as the Hazelden of torture treatment, a worldwide pioneer and leader charting the course in its field. “What’s really important is that the Center for Victims of Torture is based here in Minnesota and has a global impact,” says Robin Phillips, executive director of Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights. “It is a way that people concerned about human rights issues and torture can become involved in the world community.”

CVT OPENED in May 1985 as an independent nongovernmental organization housed in the International Clinic of St. Paul Ramsey Medical Center. Two years later, the center moved into a small house on the University of Minnesota campus. In early 1991, the center moved again, this time to its current home on East River Road, rented from the University for $1 a year. Last May, a St. Paul site in the city’s Historic Hill District opened.

The center’s mission is fourfold: treatment, training, research, and advocacy. But its work has not been confined to the Twin Cities. Since 2001, CVT has provided its services to refugees in Guinea and Sierra Leone. It is contemplating expansion to Liberia.

In 2003 (the last year for which complete numbers were available), CVT trained 3,500 doctors, nurses, social workers, therapists, teachers, and school psychologists to recognize signs of torture and respond appropriately. The center trained staffs at most torture treatment centers, in the country and another fifteen around the world.

Last September, CVT organized a groundbreaking international symposium, New Tactics in Human Rights, in Turkey that explored new tactics in human rights strategies. More than 400 human rights workers from more than eighty countries attended.

Since 1992, CVT has had an office in Washington, D.C. Its early efforts pushed the first Bush Administration to pay the country’s arrears to the United Nations Volunteer Fund for Victims of Torture. More recently, CVT has lobbied for an independent investigation of Abu Ghraib by the United Nations special rapporteur on torture and to have the Torture Victims Relief Act funded at the levels appropriated.

The centers work in public policy, research, and training has extended from its original work treating victims of torture, but healing work remains its primary raison d’être. “Our intellectual core derives from our work with clients,” says Douglas Johnson, CVT executive director since 1988.

THE FIELD OF treating torture survivors is relatively new, barely older than the CVT itself. Rosa García-Peltoniemi, CVT director of client services and a clinical psychologist at the center for sixteen years, has been learning on the job as long as anyone. She dispenses her wisdom articulately and carefully, with a faint Cuban accent.

Clients who seek CVTs services are usually suffering anxiety and depression, universal consequences of trauma. Like Oketch, they usually feel isolated and unable to trust. Many are separated from their spouses and children, who were left back home in dangerous situations when the torture victims fled for their own safety. The trauma often interferes with daily functioning, such as the ability to parent, hold a job, and form meaningful relationships. As émigrés, they might experience heightened feelings of isolation because of language barriers, not knowing people, being unfamiliar with surroundings, and lacking the savvy to access social services. Furthermore, they may be suffering physical pain, and often they are short on financial resources. To classify their condition as posttraumatic stress disorder doesn’t jibe with García-Peltoniemi.

“We’re not working post trauma,” she explains. “We’re working in the trauma.”

When Gregory Batey arrived at CVT in October of 2003, the torture had stopped, but the torment continued. As is common among survivors, the former journalist and political activist from Cameroon suffered from repeated nightmares.

He worried about the well-being of his wife and their five children, ages eight to eighteen, whom he’d left behind brutality he endured had robbed him of his hearing in one ear, limited the use of his left arm, elevated his blood pressure, and left him nearly paralyzed in his right hip. He was broke, unable to work, and staying with an acquaintance from Cameroon Survival had presented additional challenges.

At each intake meeting, the staff asks a new client what his or her goals are. Identifying therapy goals immediately involves the client and turns attention toward the future. Batey, for instance, listed physical health as his first goal. Three-quarters of CVT clients continue to suffer from physical injury resulting from torture Batey’s therapy team—which includes a physician, psychiatrist, social worker, nurse, psychotherapist, physical therapist, and sometimes a massage therapist—arranged for a successful hip replacement, prescribed medication to treat his blood pressure and other ailments, and made appointments with an ear specialist.

A recent CVT study found that clients, who may come as often as they like for as long as they need, usually visit regularly for about eighteen months, using psychotherapy an average of twenty-one sessions and social services an average of eighteen sessions. Oketch attended weekly or monthly therapy sessions for one year, then came only once every three months. He knows to call or stop in as needed, when events such as 9/11, the Iraq war, or a nightmare trigger his trauma. He also visits the center as a board member these days. Batey, who has been coming to the center for more than a year, reports progress with the nightmares and regaining trust, but he knows he’s not ready to leave. The torment is not that quickly terminated.

Batey, fifty-two, is a large man, six feet and more than 200 pounds. He sits in a room at the East River Road house, dressed in a gray and white striped shirt, gray sweatpants, and new Fila tennis shoes CVT helped him buy. A chrome cane rests at his side. “I wasn’t born handicapped,” he says in a rich accent. “Now, I just sit in one place and develop weight.”

He suffers simple indignities. He can’t bend to trim his toenails, which have cut holes in his socks. “Who else can do that for you other than a close relative?” he asks rhetorically. But when a CVT staff member overhears this, she tells him the nurse will do it for him. He smiles gratefully and expresses surprise that the staff is willing to “spend a lot of time helping people with problems who are not their family.”

The Cameroon government imprisoned Batey seven times before friends managed to sneak him out of the country. His “crimes” included reporting a workers’ strike that embarrassed the government and holding office in the opposition party. As he leans forward to describe the situation, his eyes widen, his voice rises.

“Being in jail in Africa is not the same as in America,” he says. “You are locked in the nastiest cell you can imagine. Thirty men in a room this size [eight by ten feet]. You shit in a tin bucket. If a white man like you was put in there, they’d be packing out a dead man.”

The policemen hung him naked on a balançoire—”on a bar, like an animal ready for smoking.” They beat the bottom of his feet and shocked his genitals.

He constantly feared for his life, even when he wasn’t imprisoned. He eventually escaped his torturers, but the experience pursued him.

ROSA GARCIA-PELTONIEMI names three major stages in recovery: safety and stabilization, remembrance and mourning, and reconnection.

Safety and stabilization. CVT staff considers no detail too small in putting a client at ease. Staff will ask if a person wants curtains in a room drawn or open, where the client would like to sit, how to leave phone messages. “Every interaction has implications,” García-Peltoniemi says. “Our staff is trained to be thinking about that and acting accordingly.”

Even the buildings are designed to be welcoming and noninstitutional. Walk into the Minneapolis or St. Paul house, both hundred-year-old restored Victorians, and you find warm dark wood, soft carpets, muted angles, hanging art, and flourishing plants. There’s nothing clinical or institutional about the place—”You don’t smell hospital,” Oketch says—it feels like a home.

Remembrance and mourning. Every Psych 101 student can tick off the five stages of grief made famous by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who first identified these, stages through her work with European concentration camp survivors. The grieving process that García-Peltoniemi witnesses, however, is complicated by culture and conditions. Much of it comes in spurts. CVT clients grieve bits at a time, their energies become consumed by responsibilities of their new life, then they may encounter another loss and grieve some more. Many suffer ongoing loss—60 to 80 percent of CVT’s clients are separated from children and/or a spouse.

In his third week, Oketch delved into a grief he’d long avoided. He had not let himself cry when he witnessed the murders in prison. Nor had he let himself cry over the death of his family members. At CVT, he finally let go. He wept the entire hour with his therapist. Huge sobs that shook his body. He went home and wept through the night. The next morning, he started to feel better.

Reconnection. Oketch still had a long way to go. He had left behind, four children and a wife, who later died of a heart ailment. It took him two years before he was able to start connecting with others. Survivors begin to reestablish normal social relationships once they have learned some skills in managing their symptoms, says García-Peltoniemi. Oketch began socializing with groups of other Africans. He met a woman and fell in love.

The healing process is more spiral than linear. García-Peltoniemi points out that there are triggers that can vividly bring back the past, causing the survivor to feel emotions, even sensations, felt at the time of the trauma. Gunshots, television violence, even a car accident can bring on another wave of grief or nightmares. The ability to see a nightmare for what it is and carry on with the day serves as a measure of progress.

Not all of CVT’s clients’ Stories have happy endings. There are those who struggle with guilt and shame even years after the torture. Some clients consider taking their own lives; a few have succeeded.

But that’s unusual. The people who reach CVT are survivors. They’ve survived the torture, escaped their country, and made it to safety. They credit faith and family for helping them survive. “They’re a highly selective group,” García-Peltoniemi says. “They’ve gotten to the United States, and not only the United States, but to the middle of the United States and our god-awful climate.” She laughs.

BEIGE PAINT flakes off the side of the East River Road house. Inside, on an August afternoon, most of the offices are vacant. Most of the staff is out on a two-week furlough, an effort to trim $600,000 from CVTs $7.2 million annual budget. Like most nonprofits in the post-9/11 economic downturn, CVT has seen its donations and investments dwindle. During the past two years, the center has cut sixteen positions, reducing its staff by more than 20 percent. It drastically reduced its training program and has had to limit the number of new clients, taking on only the neediest.

Yet, the center is thriving. It opened its new house in St. Paul last May. This past summer, the UN granted the center special consultive status. The New Tactics symposium thrust CVT to the front of the international human rights effort.

Necessity has mothered another CVT invention in the form of group therapy at the St. Paul house. In the face of budget cuts, group therapy has become a cost-effective alternative to individual therapy, but research shows that groups offer particular “curative factors” as well. When someone hears another person describe a similar experience, the member realizes he or she is not alone, not terminally unique, but that there is a universality to the experience. In a group, members also experience a sense of belonging, a powerful antidote to the isolation most torture survivors endure. Groups also lead to socializing, an important element of forming connections.

“There are therapeutic benefits of being in a group that make a strong case for working with clients in more of a group approach,” says Chuck Tracy, a clinical social worker at CVT. He sees the groups not as replacing individual therapy, but complementing it as an evolution of services. The Minneapolis house is considering the implementation of more groups.

RICHARD OKETCH HAS stopped running. He hasn’t healed—perhaps no one ever heals completely after being tortured—but he has progressed. His symptoms have lessened. His coping skills have increased. He can go to bed at night and sleep a full nights sleep.

The nightmares still visit, though less frequently. He no longer dashes out of bed and injures himself.

When the machetes slash again— Oketch bolts upright, soaked in sweat. Eyes wide. “Richard,” says his wife. The woman he loves. The mother of their two children. “Richard, it’s all right.” And it is. He knows it is.

© John Rosengren