A team of huskies barreled down the trail, straining at their traces, pulling a driver hellbent for Nome. It was early in last year’s famed Iditarod sled dog race, and Dallas Seavey, the defending champion, rode upright behind his team of 14 dogs. They’d reached a treacherous stretch of Alaskan backcountry where the wind had scraped the earth bare in patches, and he felt his sled jerk uncertainly beneath him. Losing control here, Seavey knew, could spell ruin for a team early in the grueling race from Anchorage to Nome, a journey across nearly a thousand miles of rugged wilderness.

It was the 50th running of the contest, and stakes were high: Seavey was vying for an unprecedented sixth victory. Such a win could solidify his reputation as the greatest musher of all time. But as the sport’s most visible star, he had also become a lightning rod for critics of the dogsled industry, and it seemed he might never outrun their reproach.

He heard the yelping of dogs carried on the wind. The cries grew louder, and soon Seavey came upon them, a team of huskies on the side of the course, their sled tangled in the brush. Instantly he recognized the driver: It was his father, Mitch Seavey, a three-time Iditarod winner who, in addition to being Dallas’s mentor, happened to be his primary rival. Mitch’s dogs had flown down an icy creek bed and veered off course; as he tried to turn sharply back to the trail, his sled tipped over and slammed him to the ground. The impact had bruised his ribs and torn his labrum.

Dallas had a quick decision to make. Here was his father, in need. If he suddenly reined in his dogs and mingled two excitable teams, he might make the situation worse. But something else spurred him on, and Mitch understood. They both desperately wanted to win this race. “He saw me, but I didn’t expect him to help me,” Mitch later said. “He had a tiger by the tail at the time.” Dallas streaked by his injured father.

That fierceness and focus came naturally to Dallas. About two weeks after his 18th birthday, in 2005, he became the youngest competitor to ever finish the Iditarod; at 25, he became the youngest to win it. But his fifth victory, in 2021, carried an asterisk: He triumphed on a truncated 848-mile course, shortened to prevent the potential spread of Covid in rural Alaska. Diana Haecker, the editor of The Nome Nugget, which has reported on the Iditarod since the race’s inception, said there was a sentiment circulating on social media that he’d won four bona fide Iditarods and one abbreviated one. To convince those skeptics, she said, “He has to finish one more in Nome to have that bona fide fifth.”

To the sport’s critics, however, no amount of victories can erase their perception of Dallas’s wrongdoings. As he and his father came to dominate the Iditarod, they also became ensnared in a long-running debate about the very nature of dog sledding. Are huskies at their happiest running hundreds of miles a week, as mushers maintain? Or, as animal rights activists insist, are they victims of callous human ambition, sometimes required to endure unfathomable hardship? The conflict has embroiled both the Iditarod and the Seaveys in a fight that could change the sport forever—and, if some have their way, maybe even lead to its demise.

Dogsledding’s most powerful antagonist, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, is as intent on terminating the race as Dallas is about winning it. For years, the organization has been quick to publicize allegations against the Seaveys, whom critics have accused of mistreating their dogs. Then, six years ago, hours after the finish of the 2017 Iditarod, four of Dallas’s dogs tested positive for a banned opiate painkiller. Critics seized upon the doping violation as evidence of the race’s abusive nature and ratcheted up their public vitriol. Even though Dallas was eventually cleared, the controversy rocked the tight-knit mushing community, with its reverberations still being felt.

All the while, Dallas maintained that he never gave his dogs any banned substances, and after three years in self-imposed exile, he returned to the Iditarod in 2021 and won. A year later, however, there was still the sense that he was racing for validation. The question persisted: If he didn’t dope his dogs, who did? Not all were satisfied with his explanation. And there was a sense, for some, that his story was still shrouded in mystery—about what he might have done or, maybe, about what had been done to him. “Human nature,” Haecker said, “is such that people always envy the successful.”

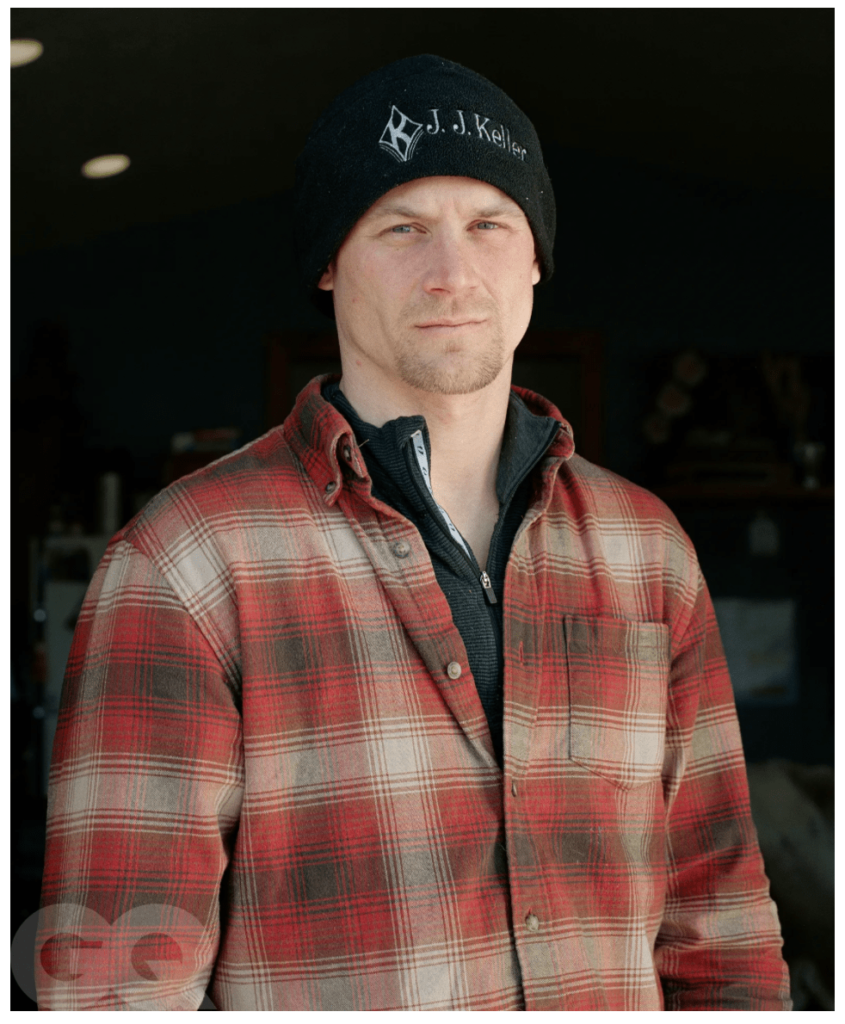

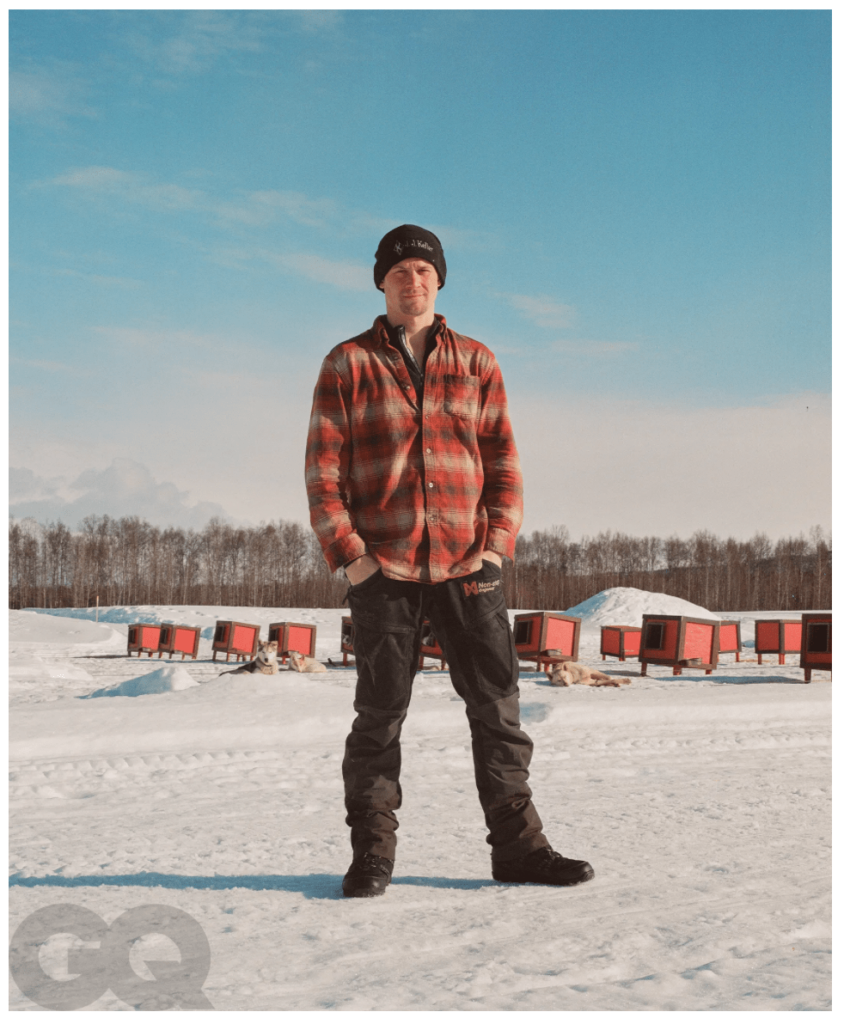

Dallas Seavey’s kennel, where he houses his 110 sled dogs, lies off the grid, outside the town of Talkeetna, about a two-hour drive north of Anchorage. Other than moose, there are no neighbors in sight. Last winter, in the days just before the start of the Iditarod, he showed me around the compound. After a heavy snowfall, the power had gone out in town, but thanks to two generators and a patch of solar panels, Dallas’s own grid was still running. This is where he made his home, in the wilderness with his dogs.

Spread across a field were neat rows of red wooden dog houses, 99 of them in all, each capped with snow. The dogs were tethered to zip lines allowing them to move back and forth and interact with their neighbors. Known as Alaskan huskies, these sled dogs aren’t actually a breed but a mongrel. Over the years, native Arctic dogs have been crossed with a number of breeds—setters, pointers, shepherds, border collies—in search of the right blend of speed, stamina, and toughness to endure the rigors of frontier life and sled dog racing. Dallas, after an apprenticeship under his father, had spent years on his own breeding what he called “superdogs”—elite canines capable of leading a team to victory in the Iditarod. His huskies’ mottled coats reflect their roots; they had no uniform appearance other than their lean, muscled physiques. “They all look different,” Dallas said, “but they’re the same in their insane desire to run.”

Raising and racing animals of this caliber is an expensive venture. Over his career, Dallas, who is 36, has won more than half a million dollars at the Iditarod, where the 2022 prize for finishing first was just over $50,000. But competing in the sport on the grand scale that Seavey does costs him plenty, even with the backing of several sponsors. His Talkeetna kennel is a sprawling operation tended to by eight paid staffers that Seavey houses on-site. As he showed me around, he ticked off the start-up expenses he incurred in creating the place: clearing the topsoil; putting in a road; building a small lodge, staff cabins, and an equipment shop, plus the dog houses. He wants to add a dedicated space for canine massage and electromagnetic therapy. “Talk about a financial purge,” he said. “It’s never-ending.”

In addition to the cost of maintaining his facilities and paying his eight staffers then living at the compound, Dallas estimated that it set him back $1,500 a year to feed each dog. On top of that there’s vet care, sled maintenance, gear, and booties—the dogs go through them by the thousands, and for the 2022 Iditarod alone they cost him $1,800. Dallas’s summer business, giving sled dog rides to tourists, offsets some of these expenses, but he wasn’t getting rich. “They say, ‘If you want to become a millionaire in dog mushing, you’ve got to start as a billionaire,’” he said.

One of his most unexpected costs was perhaps the bill he racked up when he hired a legal team and a P.R. firm after the doping controversy. Soon he would be stepping back from the spotlight, and the scrutiny that had been following him: Dallas told me the 2022 Iditarod would be his last for a while. He said he’d continue to run his kennel and his tour business, but he was taking an extended hiatus from racing, and planned to spend more time with his daughter, Annie, then 11.

As we walked down the lane, a dark dog bounded up to greet us. Dallas rubbed him behind the ears. “Hero’s a big boy,” he said, “but he ran like a little dog.” A veteran of his 2015 winning team, Hero was now retired. Dallas took me inside his lodge, where he introduced me to an Alaskan legend: Beatle, his lead dog on three Iditarod-winning teams. Now he was curled up on a chair. “Beatle, you lazy sack of bones,” Dallas teased. “I’ve run over 30,000 miles with that dog. When he moves, he has a beautiful, smooth gait. Now he runs an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening, then he’s happy to spend the rest of the day sleeping.”

Back outside, Dallas led me to the back two rows of doghouses, where he kept his varsity. He had narrowed the candidates for his 2022 Iditarod team to 20 but had yet to settle on the final 14 he’d take with him to Anchorage. Regardless of which dogs he selected, he was confident his final lineup would be “as good as any team in the world.”

He paused to pet a brownish dog standing outside his house. “Canton, you’ve got a goober in your eye,” he said, wiping the mucus away with his finger. Two others, Swifter and Mustang, shied away from us. “Mustang takes half a day to warm up to someone new,” Dallas explained. “Swifter takes a little longer. If there’s something scary, I’m his security blanket. He’ll be right up next to me.”

Indifferent to the falling snow, he stood with his dogs and talked at length about the importance of anticipating their needs—food, rest, massage—and building their trust in him. “If you understand them, how their brain works, and communicate with them on that level,” he said, “you can accomplish some pretty amazing stuff.”

Curiously enough, the “Father of the Iditarod” was a man who grew up in the Oklahoma Dust Bowl. Joe Redington, Sr., started training sled dogs after he moved to Alaska, and used to hook up 200 of his dogs to pull a school bus as a sort of carnival trick. This was in the mid-20th century, a time when sled dogs were being replaced by snow machines for delivering mail and supplies, and Redington, Sr., wanted to honor the animals’ contributions to Alaska’s way of life. To commemorate the state’s frontier spirit, a course was devised that followed the Iditarod Trail, the route that thousands trekked across Alaska in the early 20th century after gold was discovered in Nome.

Mushers and their teams forged over the Alaska Range, along the Yukon River, through the Gold Rush settlement of Iditarod, by then a ghost town, and across a stretch of frozen Bering Sea. Along the way, they endured wind chills well below zero, risking frostbite and hypothermia. Thirty-four dog sledders contested the first race, but the ultimate opponent was nature itself, the challenge just to reach Nome. Twelve mushers would drop out along the way, and over the next half century, roughly a third of those who started the race wouldn’t finish it.

The first race was held in 1973, and among that inaugural field was Dan Seavey, who had come to Alaska from Minnesota to take a job teaching history and bought a sled dog a month later. “That was the beginning of my love affair with dogs,” Dan, now 85, recalled. After finishing third, he competed in the Iditarod into his seventies, mentoring younger mushers along the way, including his son Mitch and grandson Dallas. “He’s one of the best at developing dogs,” Dallas said, “especially lead dogs.”

But Dallas would learn the most from his father. A one-time commercial fisherman who spent some time in real estate before opening a dog kennel, Mitch first competed in the Iditarod at 22, and became known for his tenacity and meticulous preparation. Dallas absorbed those qualities early: Bedtime didn’t come until his chores were done, which included picking up dog shit and changing straw in the doghouses of the kennel. Mitch and his wife, Janine, homeschooled Dallas and his three brothers, two of whom would also one day compete in the Iditarod. “Racing was not something that just my dad did, it was something the whole family did,” Dallas said. “For us, the Iditarod was bigger than anything. To win it was the ultimate life goal.”

Mitch ran the Iditarod ten times before winning on his eleventh try, in 2004, at age 44. When that happened, everything changed. No longer was victory a quixotic notion. “To finally win after years and years of working for this goal just out of reach was a moment of revelation,” Mitch said. “We can do this, too—it’s not just for other people. It was a life shift in many ways.”

Dallas was there, standing in the chute when Mitch drove his team under the famed Burled Arch that marks the finish line in Nome. It was just after his 17th birthday, and his father had entrusted him with training his winning team. A thought began to take hold that he too would not only run the Iditarod but win it.

Five years later, at 22, Dallas started his own kennel in Willow. “I didn’t want to become a better Mitch Seavey,” Dallas explained. “My dad was entrenched in the way he was doing things, and the way others were doing them as well—it’s easy to get caught up in that echo chamber.”

Dallas pored over data from previous races. He was particularly intrigued by the Smyth brothers, Ramey and Cim, veterans who managed to keep the speed of their teams consistent throughout the race. In contrast to what he saw as the prevailing training practice of running dogs for 70 to 80 miles, resting them a day or two, then running them the same distance again the next, Dallas started doing shorter, four-hour daily runs at an average of 8 to 8.5 miles per hour—a tempo he felt his dogs could sustain over a thousand miles. “Some may consider that slow,” he said, but in those years, “8 miles per hour at the end of the race was fast. I want to have the fastest travel times at the end of the race.”

Father and son may have taken different paths, but from 2012 to 2017 they combined to win a staggering six Iditarods in a row. When Mitch triumphed for the second time, in 2013, he became, at 53, the oldest musher to ever win the race, only to break his own record four years later. That year he also set the course record with a time of 8 days, 3 hours, and 40 minutes—a performance that shattered Dallas’s mark from the year before by more than seven hours.

Mitch, a former wrestler with a compact build, hasn’t lost any swagger over the years. Dallas is slighter—5-foot-8, roughly 155 pounds—but he bristles with grit. In his teens he too was a wrestler, a high school Greco-Roman national champion. A series of concussions forced him to leave the sport at 19, but not before he’d cultivated an appetite for suffering. “The more miserable the conditions,” he said, “the better I’ll do.”

His father concurs. “He seems virtually impervious to misery and pain,” Mitch told me. “It’s not like he’s going to give up.” That’s an indispensable quality in a wilderness that shows no mercy; Iditarod lore is loaded with tales of toughness. Four-time champion Martin Buser badly sprained his ankle early in the 2014 race but continued on to Nome. In 2019, Anja Radano crashed in the Dalzell Gorge, a jagged thousand-foot descent, broke a rib and injured her leg, but gutted it out to the end. In 2021, Aliy Zirkle’s sled flipped on an icy section of the course and she crashed hard. Severely concussed and unable to use her right arm, Zirkle pushed on to the next checkpoint, where she was airlifted to a hospital in Anchorage.

Dallas himself nearly died in the 2011 edition of the Yukon Quest, an annual race that runs a thousand miles across Canada and Alaska. When his dogs broke through the thin ice of a frozen creek, he had to slosh through knee-deep water to lead them to safety on the other side in near 50-below temperatures. He stumbled and fell into the water, soaking his clothes, which quickly froze. Another musher helped him out of his ice-caked layers, and Dallas managed to make it to the next checkpoint wrapped in his sleeping bag, though not before a grim thought crossed his mind. At least if I died, I was doing what I loved.

Each race brings its own unforeseen challenges. Not long after he passed his father in the 2022 Iditarod, a little more than 110 miles along, Dallas noticed some of his dogs weren’t eating. Something was wrong.

Dallas flipped through a mental checklist of possible explanations. Stress? No, the race had started only about 15 hours earlier. It was too early. Maybe they just weren’t hungry? No, after some major efforts, his dogs had worked up an appetite. Tired? Not yet. Too soon. Some sort of bug? Must be.

About another hundred miles on, between Rohn and Nikolai, his hunch was confirmed when he spotted one of his dogs spurting green diarrhea: Some sort of stomach bug must’ve infected the team. Dallas knew that victory would be impossible with sick dogs. His challenge shifted from outracing his competition to nursing his team to health. “You can’t be afraid to lose,” he said. “You have to be willing to back off and care for the team.”

In McGrath, the next checkpoint, he gave his sick dogs a probiotic clay substance that absorbs toxins. And for an hour at a time, he carried his sickest dogs in the basket of his sled or a small trailer affixed to the rear. This provided a respite for those that were hurting, but it also put more stress on the others. Without his entire team pulling at full strength, a sixth victory became a more complicated proposition. He would have to wait and see if his ailing dogs could regain their health soon enough to chase down those ahead.

During the race, the average 50-pound sled dog needs to consume about 10,000 calories a day to replenish its energy sources, the equivalent of a 150-pound person consuming 30,000 calories, or about 55 Big Macs. That’s a lot of food—and a big logistical challenge for a dog sled team that begins long before their journey commences.

Sixteen days before the start of the Iditarod, Dallas backed up his black Dodge Ram to the loading dock of an Anchorage warehouse. Volunteers helped him unload dozens of plastic bags packed with food for himself (energy bars, meat sticks, pizza slices) and for his dogs (pork bellies, chicken skins, salmon, beef fat) and backup trail supplies (booties for the dogs, gloves and socks for himself). The bags—each with a town name inked on the side—were to be loaded onto pallets, trucked to the airfield, flown to several of the 19 trail checkpoints, and couriered by snowmachine to those where the ground was too rough to land a bush plane.

It was the kind of intensive preparation, attuned to the finest of marginal gains, that showed how much the sport has modernized over the past half century—and one of the reasons why finishing times have steadily decreased. In the late ’80s, the winner typically reached Nome in a little over 11 days. By 2010, it was de rigueur to win in fewer than nine. There are several other factors that have increased the speed: smarter training, better groomed trails, improved nutrition for dogs, lighter sleds with faster runners, genetic improvements through savvier breeding. And possibly, critics contend, performance enhancing drugs.

The month after the 2017 race, when he finished second behind his dad’s record-setting time, Dallas got a call from Mark Nordman, the Iditarod race marshal: Four of his dogs had tested positive for Tramadol, an opiate painkiller popular among professional cyclists. Dallas was concerned but figured there must be some kind of mixup or misunderstanding that would get resolved soon. But it didn’t.

Later that year, the Iditarod Trail Committee announced that several dogs in an unnamed musher’s team had tested positive for a banned substance; since they couldn’t determine whether the musher played any role in the dogs testing positive, the board was changing the rule regarding “canine drug use” so that in the future, competitors would be liable for any positive drug tests, unless they could establish that the results were beyond their control.

Dallas felt unfairly outed. Even though he hadn’t been named, he thought his identity was only faintly disguised. Meanwhile, other mushers were outraged by how the board appeared to handle the situation under a veil of secrecy. Two weeks later, after an emergency meeting, the Iditarod Official Finishers Club—which considers itself the players’ union for mushers—issued a statement signed by 83 members demanding “the release of Musher X’s name within 72 hours.” The Iditarod Trail Committee promptly obliged, naming Dallas. He immediately issued a nearly 18-minute video on YouTube in which he blasted the Iditarod governing body for its handling of the situation and declared, “I have never given any banned substances to my dogs.”

Iditarod officials randomly test dogs at several checkpoints, but the only guaranteed test is for the top 20 mushers after the finish in Nome. Dallas’s dogs’ concentrations of Tramadol seemed to suggest they had ingested it not long before they were tested. But who would do that? “I don’t think it’s logical Dallas would’ve doped his dogs knowing they’re going to be tested,” said Stuart Nelson, Jr., who has served as the race’s head veterinarian for the past 28 years.

The story not only played widely in state news but also was picked up by The New York Times, making Dallas feel like he was being portrayed as “the number one criminal in Alaska.” Other mushers publicly supported him, however, and in December 2018 the board apologized and cleared him of any involvement with the positive tests. But that didn’t make everything better. “When you print a headline, it’s a headline,” Dallas told me. “When you print a correction, where does it go?”

The board’s handling of the situation damaged its relationships with some mushers and sponsors, imperiling the race itself. A consultant group hired by the race’s major sponsors in the wake of the situation asserted in its December 2017 report that “the priority of the board should be to take immediate steps to improve their relationship with sponsors and mushers.”

Dallas boycotted the Iditarod for three years, instead twice racing the longest sled dog race in Europe, Norway’s 745-mile Finnmarksløpet. Throughout, he has maintained that he never gave his dog banned substances. In the statement he released on YouTube, he speculated about several possible explanations for the positive test, suggesting that a competitor or an “anti-musher” could have slipped his dogs the drug.

The most fervent “anti-mushers” are, of course, certain animal rights activists, PETA foremost among them. An official from the organization flatly denied any involvement. “Of course PETA did not do that,” Melanie Johnson, the manager of PETA’s animals in entertainment campaigns and the overseer of its efforts concerning the Iditarod, told me.

Regarding the possibility of any doping in the Iditarod at large, in 2017, Chas St. George, the race’s chief operations officer, told Alaska Public Media that Seavey’s dogs’ positive result was the first for a banned substance since the race started testing in 1994. Craig Medred, a freelance journalist in Alaska who has covered the race for decades, has reported on his blog that in the past “some mushers were asked to retire or take some time off from the race after being discovered with doped dogs.” Stuart Nelson, Jr., told me Dallas’s dogs were not the first to have tested positive for banned substances since he became chief veterinarian nearly thirty years ago. He could only remember one prior violation—what he described as “back of the pack, not in the money, and pretty innocuous stuff”—in which Rimadyl, a banned anti-inflammatory drug, had turned up in a dog’s urine. (The Iditarod Trail Committee’s Canine Drug Testing Manual draws a distinction between actual doping violations and positive tests that can result from dogs eating large amounts of meat from animals treated with pharmaceuticals.)

“It’s hard to say how widespread it is, but they’re training year-round, and the Iditarod is telling them when to stop using—with what the rules advise—so they don’t get caught,” Medred told me. “When you run a doping program for this long and no one is ever caught, something is wrong with your doping program.”

John Schandelmeier, who has raced the Iditarod twice and won the Yukon Quest twice, explained a possible strategy to avoid the tests during a race; you can simply make a quick stop at a checkpoint where you’ve heard there might be testing, or you can wait until your dogs are bedded down, giving them time to pee and helping to ensure that they won’t urinate again later for the tester. “You’d have to be pretty naive to think there’s not any doping going on with sled dogs,” Schandelmeier said.

When Seavey reached Cripple, roughly the midpoint for last year’s Iditarod, he had with him 12 of his original 14 dogs. They had been racing for four days. He withdrew one dog who was dehydrated, perhaps because of the diarrhea, and another who’d hurt his shoulder after stumbling on an uneven patch of trail. At the checkpoint, Dallas took his mandatory 24-hour rest, which gave him time to feed his remaining dogs, rub ointment on their paws, massage sore muscles, let them sleep, and grab some shut-eye himself.

Mitch would arrive soon, too. His shoulder and ribs ached from his crash two days earlier, but he’d managed to make up some time, and was the fifth musher to arrive at the checkpoint. When Dallas left the next evening, his dogs looked better but still not 100 percent. Only three mushers were ahead of him, with Brent Sass leading the way, three hours and seventeen minutes up the trail—not an inconceivable gap to close.

On Saturday, March 12th, Dallas opted for his first eight-hour break, in Nulato, 157 miles later, to give his team some extra rest. There he withdrew two more dogs. Swifter was still sick. The other, Ace, a hard worker, had tired, and Dallas feared he could be a drag on the rest of the team. With 393 miles to go, Dallas was down to 10 dogs and only 2 hours and 45 minutes behind Sass, who left Nulato with 12 dogs.

But Dallas had managed his team adroitly enough to pull away from his other competitors. Bruce Lee, an analyst for Iditarod Insider, the race’s online news source, assessed earlier in the week that Dallas’s and Sass’s teams possessed “strength, attitude, and power that none of the other teams matched.” Lee also observed that Sass, then 42, a veteran musher who had finished third in 2021 and fourth in 2020, had “a very hungry look in his eyes.” But Dallas was hungry himself, and his dogs were on the mend. He blew through the next checkpoint in Ruby, 70 miles past Cripple, saying his dogs were “eating like monsters.” They were starting to look again like Dallas’s dream team, the one that could deliver his coveted sixth victory.

But if such an image thrilled his fans, it repulsed the critics who’ve worked for years to end the race. The Iditarod has become, not surprisingly, a highly charged battleground for animal rights activists who make a point of being on hand for the festivities. A week earlier, at the race’s ceremonial start, in Anchorage, on March 5th, six activists working with PETA had posed as mock pallbearers carrying a sled as a coffin stacked with fake “dead” dogs. The organization has opposed “the deadly Iditarod” for decades, asserting it’s cruel and dangerous to make dogs pull sleds a thousand miles in harsh weather. PETA is not the only animal rights group that has voiced objections to the Iditarod; the Humane Society of the United States denounced the race in the mid-’90s, prompting Timberland, a major sponsor at the time, to drop its support. The claims of dog abuse gained momentum with the 2016 documentary Sled Dogs, which portrayed the industry at large as having cruel practices in breeding, training, and racing. PETA sent the film to Iditarod sponsors in April 2017, and claimed victory when Wells Fargo ended its 29-year sponsorship shortly afterward (though a spokesman for the company said at the time that the decision was based on a marketing review, noting that their investment in the race had declined since 2010).

PETA’s stated goal is to end the Iditarod, and a crucial element of its strategy is to cut off the race’s funding by shaming sponsors through petitions and theatrical protests. For example, the group staged demonstrations at Alaska Airlines’ headquarters in the Seattle area. In 2020, Alaska Airlines announced it would drop its more-than-40-year Iditarod sponsorship after that year’s race (a spokesperson for the company said at the time that the decision reflected a shift in corporate giving and was not influenced by PETA).

The organization also bought more than 100 shares of ExxonMobil stock and in late 2020 submitted a shareholders proposal urging the company to “consider eliminating sponsorships that benefit activities in which animals are exploited, harmed or killed, such as the Iditarod.” A month later, in early 2021, ExxonMobil agreed it would conclude its 43-year support of the race, citing at the time a review of sponsorships “in light of current economic conditions.”

In 2022, The Lakefront Anchorage hotel and Nutanix backed out, joining what PETA says is a growing list of 20 sponsors that have dropped their support of the race in recent years. The Iditarod has added two major sponsors in recent years, including Hilcorp and Harvest Midstream, which join GCI and Donlin Gold as the race’s “principal partners,” all of which PETA continues to pressure. “PETA will continue its protest until the Iditarod is ended for good,” Melanie Johnson told me.

In 2008, the Iditarod offered prize money totaling almost $925,000. But as sponsors dropped, so did the purse. In 2023, the race will pay out $500,000, the same amount as in 2022. The number of mushers peaked at 96 in 2008, fell to 49 in 2022, and to 33 in 2023. Despite PETA’s aggressive campaign against the race, the Iditarod leadership insists it is not facing extinction. “I don’t think the race is in danger of being shut down,” St. George told me.

Much of the debate centers around a fundamental disagreement about canine care. Tracy Reiman, PETA’s executive vice president, told me that, “‘Sled dogs’ are the same as all other dogs who want to live in a warm house with caring people.” She and other animal rights activists object to dogs being chained and kept outside in harsh weather.

Sled dog racing advocates maintain that Alaskan husky mixes with double fur coats are able to stay warm in very cold temperatures and thrive in events like the Iditarod. “Some people disagree with dogs having a job, but if we’re utilizing dogs to pull a sled, [Alaskan huskies] are the right dog for that,” says Caroline Tonozzi, an emergency and critical care veterinarian from Illinois now in her seventh year volunteering at the Iditarod. “It’s a joy to watch these dogs doing what they’re supposed to be doing—run. That’s what they’re bred to do.”

Dallas objects to the way the debate is framed as animal rights groups versus mushers because he sees himself as an animal rights activist as well. “People who do sports or activities with their dogs promote and foster and create the greatest human-animal relationships this planet has to offer.” But he often hears the same refrain from his critics: “‘Oh they’re just doing that because they as a human want success in a race or to accomplish this end or something of that nature, not for the simple fact that we have chosen to spend our lives surrounded by animals,” he told me. “And what we do beyond that is promote healthy pet ownership.”

Still, it’s undeniable that dogs have suffered and died while running the Iditarod. PETA claims that, since the event’s inception in 1973, more than 150 dogs have died racing it, a number based on past media accounts and official race reports in recent years. Iditarod officials disputed the accuracy of this figure, noting that records of dog deaths were not kept in the early years of the race, but declined to offer a tally based on their own accounts.

Ashley Keith, a former musher turned sled dog advocate, has attempted to compile an account of deaths on her website HumaneMushing.org from historical reporting and Iditarod press releases; her count, missing data on a handful of races, comes to 115. Thirty-one of the reported fatalities Keith cataloged were said to have occurred during the event’s first two years. The average number of deaths has declined in recent years: Between 2010 and 2019, a dozen dogs died. According to necropsy reports, causes of death over the race’s history have included heart ailments, aspiration pneumonia, asphyxiation after being strangled on tangled lines or getting buried in snow, and being struck by cars and snow machines.

In addition to fatalities, activists are concerned by the number of dogs that are withdrawn from the race. In 2022, just over a third of the 682 dogs who started the race were pulled before the finish. While some dogs depart for strategic purposes, others depart for reasons like injuries, fatigue, diarrhea, and pneumonia.

Over the years, the Iditarod has improved its track record. It has supported academic research on the physiology of sled dogs, and in 2022, 52 veterinarians checked dogs along the route, with seven providing care when they were returned at four locations. Dogs that are withdrawn are flown to Anchorage, where they’re given water, food, and, if necessary, medical care until they’re retrieved by their musher or one of their handlers.

In the weeks before the race, a team of vet techs at Iditarod headquarters, in Wasilla, conducted a mandatory pre-race screening on all the dogs that had been entered, drawing blood, administering EKGs, and outfitting dogs with microchips that allowed vets to access their health data. Nelson Jr., the head vet, called every musher afterward to discuss the results. Each year, he said, his team flagged on average a couple of dogs with heart conditions that shouldn’t be running the race. “May not seem like many,” he explained, “but if two dogs are identified that could’ve died, that’s good.”

But PETA has stayed on the offensive. The organization has not only targeted sponsors; it’s also called out mushers. As Dallas’s and Mitch’s successes mounted, PETA took aim at them in a series of press releases, amplifying allegations that they may have mistreated their dogs. The Seaveys have consistently denied these accusations and counter that PETA, a nonprofit that in 2021 took in $72.7 million ($68.4 from donations), seems more interested in raising money than caring for dogs. “What burns me is where you have good people who want to do something to help dogs, but they’re getting conned,” Dallas said.

He pointed out that the organization euthanizes a large number of dogs at its headquarters’ shelter in Norfolk, Virginia. According to the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer services, 718 dogs were euthanized at the shelter in 2022—66 percent of the canines they took in that year. In an email, Reiman offered context for those alarming numbers: “PETA offers end-of-life services for people who can’t afford to pay for their sick and dying animals to be euthanized as well as for animals who are elderly, feral, sick, suffering, dying, aggressive, or otherwise unadoptable.”

As one example of what Dallas says are the organization’s exaggerated claims against him, he pointed to PETA’s public comments about his “poor three-legged dog.” According to Dallas, when a moose attacked his team on a training run in 2012, the dog, Gott, suffered a spinal hernia and was paralyzed below the neck. A vet, he recalls, suggested putting Gott down. Instead, Dallas flew the dog to Oklahoma, where he says a specialist spent 18 months treating the dog and was able to revive function in Gott’s torso and three of his legs. His fourth leg, still damaged, was later amputated. The dog lived another nine years. Of the hundreds of dogs he’s had in his kennels, Dallas said that other than Gott, “I’ve never had a dog on my team who’s died or had a major injury” as a result of training for or racing in the Iditarod.

In February 2011, a small-town newspaper in Canada’s Yukon, The Whitehorse Daily Star, printed a letter to the editor from an Australian woman named Jane Stevens who described what she says was a brutal beating she witnessed at the kennel of a top musher where she’d volunteered for a few weeks. She later identified the musher as Mitch Seavey, who she said had kicked, punched, and thrown one of his dogs to the ground. “Be assured the beating was clearly not within an ‘acceptable range’ of ‘discipline,’” she wrote.

Stevens reported the incident to a number of parties—the Alaska State Troopers, the Iditarod Trail Committee, and a sled dog care group—but says she was distressed by their response. The Alaska Department of Public Safety investigated the claim, and, according to the report filed, found no evidence of an injury to the dog. The Iditarod, for its part, stressed that it was “not an enforcement agency,” and that so long as Mitch had been cleared of these allegations, he would be free to continue racing.

Mitch remembered the event differently. He told me that Stevens saw him break up a fight between two “aggressive, adrenaline-driven” male dogs on a training run, and that he used necessary force to do so. “When you have a dog trying to rip another dog’s face off, what do you do?” he asked me rhetorically.

Mitch also has doubts about his critics in general. “I’ve had PETA plants, spies in my kennel,” he said. “They just make shit up.” Both PETA and Stevens maintain that she wasn’t an undercover agent, and there’s no indication she was working for the group. David Perle, the organization’s media divisions manager, confirmed that they did plant one investigator in Mitch Seavey’s kennel for two months in 2019.

Dallas has also had to defend himself against an employee’s claim of mistreatment at his kennels. According to an incident report completed by state trooper Wallace Kirksey, in October 2017, PETA filed investigation requests with the animal care division of the local borough, Matanuska-Susitna, and the Alaska State Troopers on behalf of Abigayil Crowder, who had worked at Dallas’s kennel for several months. In a separate statement Crowder made to the Matanuska-Susitna Borough Animal Care and Regulation Board, she alleged the deaths of several puppies were the result of neglect. In the statement, she also named two handlers who “choke dogs, throw them on the ground and slap them and kick them.” (Crowder couldn’t be reached for comment but through another source in this story declined to be interviewed.)

In his incident report, Kirksey noted there were only “approximately 16 dogs” and “three apparent juvenile dogs” at the Talkeetna kennel when he visited. “I found nothing at the location to suggest the animals were not being cared for properly or to suggest a violation of Alaska Animal Cruelty or Care Statutes,” he wrote. Kirksey also reported that, on his way to inspect Dallas’s other kennel, in Willow, he ran into Nick Uphus, an officer from the Matanuska-Susitna Borough Animal Care and Regulation division, who told him he hadn’t seen any evidence of Crowder’s allegations. Kirksey noted that he reviewed a copy of Uphus’s report, which found “no violation of law,” and thus did not visit the kennel himself.

The Matanuska-Susitna Borough’s then-mayor, Vern Halter—a former Iditarod musher himself—issued a statement praising Seavey’s high standard of care and saying, “This complaint is absolutely false.”

According to the report, Dallas let go of the handler Crowder accused of dog abuse. He acknowledged to me that a litter of premature puppies died, but said a vet had told him they would not survive with their organs underdeveloped and that he had done “everything in our power to keep those dogs alive.” He points out that the inspection results vindicated him. It’s a persistent point of frustration for Mitch and Dallas—having to repeatedly deny the same allegations of dog mistreatment that have been investigated by the authorities and have not resulted in any criminal charges. “Every accusation that gets laid on you, you now have, in the 21st century, an obligation to prove you didn’t do something,” Dallas told me. “How many politicians deal with that? … I just feel like that’s the situation we get put in.”

Of Crowder’s allegations, Dallas said, “When they contacted us, we said, ‘Come out right now.’ They did the inspection the same day and saw there was actually nothing we were doing wrong.” That’s true, in the eyes of the law. The state statute defining cruelty to animals “does not apply to generally accepted dog mushing or pulling contests or practices.” Furthermore, in Matanuska-Susitna, an area that includes Talkeetna and Willow, sled dogs are classified as livestock, and as a result, some animal rights activists fear that owners of licensed mushing facilities might not be held to the same standard of care as owners of dogs kept as house pets.

For better or worse, Alaska is currently a state where the right to mush is enshrined in its legal code. The law, like the Iditarod itself, seems to reflect a frontier mentality. Mushers have strong opinions about the way they treat their dogs and what is in their best interest, but what happens at their kennels typically stays behind closed doors. “The general public will never really know what’s going on with sled dogs, whether it’s right or wrong,” said Schandelmeier, who runs a kennel in Alaska that rescues most of its dogs from shelters or other mushers. He points out that some mushers are worse than others and that Dallas, by virtue of being one of the world’s most elite mushers, merits close scrutiny. “Should readers be concerned about the way Dallas treats his dogs?” he said. “Yeah. It’s not exclusive to Dallas.” But as the sport’s current king, “he’s the poster boy right now.”

On Monday, March 14th, about 160 miles away from Nome, Mitch ran into more trouble. Outside Koyuk, where the trail bends west along the glazed beach of the Bering Sea, winds gusting up to 70 miles an hour blew his sled crossways on the polished ice and off the trail. He finally surrendered and headed back to Koyuk to wait out the storm. Though he still planned to finish, he had given up hope of winning. Others had begun to scratch outright. Twelve of the 49 mushers who started the race would drop out along the way.

Nome is the Iditarod’s Promised Land, but no place of comfort. Tucked roughly 140 miles below the Arctic Circle, the once-booming gold rush town is now a hamlet of 3,700 inhabitants. The land runs out here at the frozen sea, which has violently buckled and thrust shelves of ice onto the shore. The earth itself is tundra—a vast expanse of lunar landscape where snow drifts above kitchen windows and abrasive saltwater winds scrape the paint off houses. Nature feels bigger here, a greater force to be reckoned with.

The Nomeites abide their hardship bravely. When the Iditarod comes to town, they hail it as “the Mardi Gras of the North,” hosting two weeks of revelry that include a craft fair, a Qiviut lace-knitting workshop, dog sled tours, and plenty of old-timers spinning Iditarod yarns. The race finishes down Front Street, lined with two hotels, The Nome Nugget offices, and a mess of worn and tired bars. Farther down, the town’s convention center, which resembles a Legion hall, houses race headquarters. Inside, on Monday morning, high school cheerleaders peddled baked goods, volunteers idly chatted, and journalists worked at the rows of banquet tables. Suddenly, shortly after 11:00 a.m., the room began to buzz: Sass had reached White Mountain.

Two hours and 37 minutes later, Dallas arrived, still in second, far ahead of the others. The two would take their last mandatory eight-hour rest there, and then the dogs would be primed for the final 77-mile stretch into Nome. Talk turned to handicapping Dallas’s chances. Two and a half hours was a lot of time to make up at this stage, but he had defied long odds before.

In 2014, he left White Mountain in third place, behind Aliy Zirkle and Jeff King. They ran into a horrific storm. Zirkle made it to the next checkpoint, Safety, and hunkered down in a cabin to wait it out. On his way there, King kept getting blown off course. At times, all he could see was a brown wall of blowing dust and ice. He finally curled up with his dogs and—fearing for all of their lives—the four-time champion eventually flagged down a passing snowmachine for help, knowing that such assistance would automatically disqualify him. Dallas passed Zirkle and King in the nocturnal storm without knowing it. When he reached Nome, he didn’t realize what had happened until a cameraman told him he’d won.

“That’s the drama I will never forget in my life,” Haecker said. “At the end of a 1,000-mile race, going through every hell you can think of, exhausted, beaten down by Thor’s hammer—to keep it together in that situation, it’s one of the greatest wins ever.”

Eight years later, a final push through another perilous night would again decide his fate. Sass left White Mountain on Monday evening at 7:05 p.m., knowing Dallas would soon be on his tail. Dallas left at 9:42 p.m., thinking, I’m going to need Brent to make some mistakes. The five-time champion’s team of eight dogs “took off like a bullet,” he said, finally running like themselves. In Nome, fans went to bed not knowing which musher they’d be cheering first down Front Street the next morning.

In the moonless night, the winds raged along the final stretch, gusting up to 62 miles per hour. Sass fought to keep his sled on the icy trail, but a blast knocked his team down the hillside and they tumbled into the darkness. When they stopped, the dogs huddled together, shaken. Sass turned on the light mounted to his sled’s handlebar and searched for the trail. Behind him, Dallas’s team ran at a steady clip, slowly gaining ground. All the while, Sass feared the sight of Seavey’s headlamp cruising by. Finally, from the bottom of the hill, the beam of Sass’s light glinted off the reflective tape of a trail marker. Sass managed to coax his team up the hillside, onto the trail, and back into the race.

In Nome, a crowd of several hundred had gathered on either side of the finishing chute by 5:30 Tuesday morning, illuminated by television spotlights. An announcer with a microphone charted Sass’s progress on a monitor: “Brent is up off the ice.” A moment later: “He has made it onto Front Street.” Sass’s headlight beamed a small point in the distance, growing brighter.

Then there they were, his team of 11 dogs trotting in fluorescent yellow booties up the chute and under the Burled Arch to the applause of the crowd and the clatter of cowbells. A dazed and weary Sass told those gathered, “I’m still kind of numb. I haven’t been able to sleep.”

An hour and eight minutes later, the scene repeated itself with Dallas’s arrival—minus the photo shoot of the champion with his lead dogs draped in garlands of yellow roses. He had gained more than an hour on Sass over the final 77 miles. Had the race been longer, he likely would’ve passed his rival, but, alas, Dallas had run out of trail.

The third place finisher, Jessie Holmes, did not arrive for almost another 13 hours. The others would meander in over the next four days, with the last arriving just before midnight on Saturday. Mitch didn’t complete his 28th Iditarod until Wednesday morning at 10:19. Snow encased his mustache, and his ribs hurt. Only a couple dozen fans showed up to greet him. When Dallas hugged him in the chute, Mitch quipped, “You’re here?”

Dallas would later take a seat in the convention center after some sleep and a solid meal to reflect on the race. His face was windburnt, his lips were chapped. He was disappointed that a sixth win had eluded him, but he declared victory of a sort. “I’m as proud of this race as any I’ve run,” he said. “I didn’t win, but I had success in being able to manage my team.”

In the end, that’s what sets apart the good mushers from the great. “I don’t care about the victories,” Haecker said. “Looking through the eyes of a musher, the way he handles his dogs—motivates them, understands them—for me, that puts him up there in the pantheon of great sled dog racers.”

And yet he had fallen short. He had not yet established himself as the undisputed greatest-ever with an unprecedented sixth win, or gone out on top. But he remained firm in his resolve that this, for the time being, was his last Iditarod.

Immediately after Sass’s finish, before Dallas even got to Nome, PETA issued a statement condemning Sass, declaring all he had won was the “cruelty crown,” and asserting ominously, “The days are numbered for crude, outdated entertainment like the Iditarod.”

When Dallas braked his team under the Burled Arch, Nelson Jr., the head vet, moved in with his team to check the dogs. Dallas stepped off his sled and hugged his daughter, Annie. Next, he hugged his two lead dogs, Prophet and his half-brother North. He asked Annie to get a picture of him with the pair. “It’s probably the last time we’ll be here together,” he said.

Nordman, the race marshal, who had informed him five years earlier that his dogs had tested positive, approached, this time with praise. “That’s the best managed team I’ve ever seen,” he told Dallas.

Dallas smiled. He turned, walked back to his sled, mounted it, and invited Annie to stand beside him. Then called to his team, “Ready, boys.” And they set off, trotting through an opening in the chute, away from the crowd and down the street, disappearing into the darkness of the belated dawn.