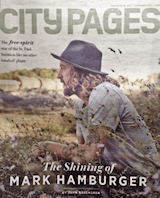

Mark Hamburger, this summer’s star pitcher for the St. Paul Saints, is like no other ballplayer I’ve met. He reminds me of two other iconoclastic pitchers, Jim Bouton and Bill Lee — smart, thinks for himself, unafraid to speak his mind. At 29, Hamburger’s still finding his way, still writing his story.

And he’s quite the author.

Here’s a guy with a 90+ mph fastball who prefers yoga to lifting weights, Whole Foods to McDonald’s, the Tao over Sports Illustrated, his ’89 Oldsmobile station wagon over a new Audi. He’s comfortable talking about the way a Higher Power works in his life, is not carrying a cell phone, and lugs a hard-shell blue Samsonite on road trips. Other than the fact he lives in his parents’ basement, he’s far from your typical millennial, let alone professional ballplayer.

The CliffsNotes on Hamburger’s career read like this:

Local junior college flunkout signed by the Twins at an open tryout. Traded to the Rangers, rose quickly through the minors to join the team for its 2011 World Series run. Demoted to minors, twice busted for smoking weed, saddled with a 50-game suspension. Graduated Hazelden and did a stint with the Saints in 2013. Resigned with the Twins, spent all of last summer at AAA Rochester, but passed on the chance to pitch as a reliever in the majors because it wasn’t what he wanted. Wound up back with his hometown team.

The full story is even better.

Hamburger perches on the back of the bench in the Saints’ dugout. A flotilla of white clouds sails across the blue ocean sky. The night before, Hamburger won his seventh game in seven decisions. He has already done an hour of Vinyasa yoga as part of his recovery regimen and is at ease.

“The defining moment, my biggest downfall, was those two failed drug tests within two months,” he says. He looks me in the eye, his Confederate grays unblinking. “Everything caught up with me. It’s exactly what I needed.”

Eddie Gaurdado famously quipped, “What? I was traded for a Hamburger?”

Hamburger does not litter his words with “um,” “like,” and “you know.” He speaks in complete sentences — sincere, smart, articulate.

He started smoking weed as a teen and kept smoking into the big leagues. But somewhere along the way it stopped providing relief and began causing problems. In Center City, he surrendered and started to put things right in his life. His left arm, his nonpitching arm, has become a metaphor for how he lives now.

He pushes up a sleeve to reveal a kaleidoscope of interlinked geometric shapes. Each represents a loved one: his older sister, his two grandfathers, three friends who passed away. The design is a work in progress. He plans to add his mom and dad along with his grandmothers. “This arm I created to honor friends and keep people in my memory,” he says.

Hamburger points to the largest shape, which looks like a pattern drawn by a Spirograph. “Picture a diamond a foot long inside each one of us,” Hamburger explains the tat’s significance. “Each diamond has 1,000 facets, yet each facet gets covered with dirt and tar. Every day I have something to clean, something new to rid myself of or something to polish.”

He looks at me with an open, guileless face.

“My intention is that I always have room to grow. It is the job of the soul to clean each facet until all of them shine brilliantly, reflecting the colors of the rainbow.”

Can you imagine having a conversation like this with Joe Mauer?

Nobody aspires to peak with the Saints, who play in the American Association, one of the lowest rungs of minor league baseball. Players see their time here as a foothold on their way to larger ambitions. For a lucky few that means the major leagues.

Yet here’s Mark Hamburger, who’s already spent time in the majors, where he appeared in eight innings over five games and played at the minor’s highest levels, pitching for the modest Saints.

“I’m surprised he’s still here,” says manager George Tsamis, briefly a major league pitcher himself. “He deserves to be in Triple-A, but I’m glad he’s with us.”

Of course he is. Hamburger’s the team ace, with a record of 11-2. He’s led the league in wins, complete games, innings pitched, and winning percentage.

Hamburger has the speed — he throws in the low 90s — and the control — 70 percent of his pitches have been for strikes — that major league scouts value. The consensus seems to be that it’s only a matter of time before he returns to The Show. Yet for now, he’s here because, well, he’s just not like other ballplayers.

Steve Hamburger remembers the first time he played catch with his son. Mark was three. “He threw the ball to me, just a rocket, straight and right at me,” Steve says. “I threw it back to him, and he did it again. Usually kids throwing for the first time are pretty dorky, but I could tell from those first two tosses that he was a natural.”

Mark is the third of Steve and Cheryl’s three kids. He did everything full speed, even walking in his sleep. When there was a call home from the school, they knew it was a teacher complaining about Mark. He rebelled at school, church, everywhere.

He liked sports but was skinny and did not appear to be the next Dave Winfield. He played basketball, rugby, tennis, football and, of course, baseball, though he didn’t make the Mounds View High varsity team until his senior year. That fall, as a wide receiver, he caught 16 touchdown passes, a testament to his budding athleticism. He grew eight inches from the end of his junior year to graduation.

Pro scouts weren’t exactly lighting up his phone, and his grades weren’t going to get him into Vanderbilt University, so he wound up at Mesabi Range College. There, he shone on the mound (11-0, 0.65 ERA) but not in the classroom (he was academically ineligible to enroll a second year).

So in the summer of 2007, Hamburger and a buddy impulsively attended a Twins tryout at the Metrodome.

The Twins liked what they saw: a 6-foot-4 20-year-old who hit 93 mph on the radar gun six times in a row. Within days, he was pitching for their rookie team in the Gulf Coast League.

Hamburger hasn’t cut his hair for more than a year, when he buzzed it close to his scalp for the Twins’ spring training. Knowing he already had “an outrageous personality,” he did not want his long hair to compound any misconceptions of him in the conservative organization.

He has let it grow since, more than 16 months, and it’s taking on a personality of its own; long, light brown locks that would make Samson blush. At first glance, that wild mane could give the wrong impression. Before I met Hamburger, Tsamis, the Saints manager, told me, “Don’t let the hair fool you. He knows what he’s doing.”

He’s right. Most ballplayers traveling through Fargo, Winnipeg, Lincoln on the American Association circuit can tell you where to find the best burger, the cheapest pitcher of beer, the preferred strip club. When Hamburger hits a new town, he scouts out the co-op grocery, an organic restaurant, and a yoga studio, while riding on his longboard.

At home, where he lives with his parents in Shoreview, he enjoys hanging out with them in the backyard overlooking a nature preserve, chilling with teammates after a game at the Ox Cart or Bulldog, playing Frisbee golf, and paddleboarding.

Those who know Hamburger use different terms to describe him: free spirit, goofball, hippie. But they mean it in a good way.

His agent, Billy Martin Jr. (yes, the son of that Billy Martin), tells it this way: Once Hamburger showed up on his radar, he asked a friend, Rangers pitching coach Mike Maddux, what he thought of Hamburger.

“He looked at me real seriously and said, ‘That kid is messed up.’ Uh-oh, I thought. What’s wrong here? ‘Yep, that kid is messed up in a really good way.’”

Among the Saints, everyone agrees Hamburger’s a great teammate. He could be aloof and arrogant. After all, he’s been to The Show. He could lord that over his teammates, drop names like those of former teammates Josh Hamilton, Mike Napoli, and Michael Young. But it’s not like that.

Hamburger’s the guy singing and dancing in the clubhouse. He choreographs home run celebrations in the dugout. He works with younger players. “Guys love having him around,” Saints pitching coach Kerry Ligtenberg says. “He’s always trying to pick them up.”

When the team left on a June road trip to Sioux City, Hamburger wasn’t scheduled to pitch. The plan was for him to stay in St. Paul. Instead, he drove down to be with his teammates. They appreciated that.

When catcher Maxx Garrett joined the team a week into the season, the Washington state native didn’t know anyone in town and didn’t have a car. Hamburger became his chauffeur. He also gave him a powered longboard so he could get around on his own.

One night, when Hamburger drove Garrett home after a game, Garrett discovered he had forgotten his keys and locked himself out. Hamburger invited Garrett to stay at his house. “When I woke up, he had fixed eggs, oatmeal with blueberries, and orange juice,” Garrett said. “It was like being at a B & B.”

In August 2008, Hamburger’s second summer with the Twins organization, pitching for Elizabethton in the Appalachian League, he was traded to the Texas Rangers for Eddie Guardado, who famously quipped, “What? I was traded for a hamburger?”

Hamburger climbed through the Rangers’ minor league ranks with stops in Clinton, Iowa; Hickory, North Carolina; Bakersfield, California; Frisco and Round Rock, Texas, until he made his Major League debut on August 31, 2011.

He has a poster of himself delivering a pitch in his red Rangers jersey, but does not remember the details. He was too jacked on adrenaline. (He retired Tampa Bay 1-2-3 in a single inning of work.) Disappointed not to be put on the Rangers’ playoff roster, Hamburger consoled himself in Colorado during the offseason smoking bales of marijuana.

The following summer, he was back in the minor leagues, pitching for the Rangers’ AAA team in Round Rock, but not very well. They released him in June. The San Diego Padres picked him up, but released him in less than a month. Houston claimed him off waivers, and he finished the season with AAA Oklahoma City.

When he failed his second drug test in February 2013, Houston promptly released him. Hazelden picked him up. Hamburger initially resisted rehab, but deep down, he knew he had a problem. So did his parents. Steve Hamburger could see how weed was controlling his son.

“Every time he hopped in the car and drove down the street, I was a wreck, praying ‘God, don’t let anything happen to him.’”

The healing began at Hazelden. There, father and son had a long, meaningful conversation. “It was the first time in 10 years that we had talked for more than 10 minutes,” Steve says. “There was something settled in his mind. I could tell he had accepted that he needed to change.”

At the end of Mark’s 30-day stay, the treatment staff recommended aftercare, noting that the majority of people who did not attend aftercare went back to using drugs. That bit of advice did not have the intended effect upon Hamburger. It simultaneously offended and inspired him.

“Did you just tell me if I don’t give you more money I will fail?” he asked. “That gave me more incentive.”

He signed with the Saints for the 2013 season, on a mission to stay clean and revive his career. Because the Saints play in a league independent of Major League Baseball, his 50-game suspension did not apply.

Despite a 6-8 record, Hamburger put up some respectable numbers, including a 3.26 earned run average. He also demonstrated durability, setting a club record for most complete games in a season (five), tops in the league. His performance was good enough to impress the brass across the river. The Twins purchased his contract and assigned him to its AA team in New Britain, Connecticut, to start the 2014 season. He pitched eight games after serving his suspension and was promoted to AAA Rochester.

Hamburger spent the balance of the 2014 summer and the entire 2015 season in Rochester, only a rung away from the major leagues. He could have returned to Rochester this year with a very good chance of being promoted to the parent club, but it would have been as a reliever. He wanted to be a starter.

So he parted ways with the Twins last November. He had a chance to sign with the Chicago Cubs, who gave him a tryout, and with the Miami Marlins, who wanted to sign him after he won the Saints’ opening game this year. But Mark said “No thanks.”

Not many guys would have the cojones to buck opportunity that way, but Hamburger was intent upon doing it his way this time, more as an act of personal integrity than outright defiance.

He does not want to simply fill a role with a team. He doesn’t want to be shuffled around at the whim of an organization. He wants to be a starter, like his favorite pitcher of all time, Satchel Paige, the rubber-armed wonder renowned for his control and ability to pitch until tomorrow.

“Satch was a starter,” Hamburger says. “Only starters can get a no-hitter or pitch a perfect game. When I think of pitching, I think of going nine innings. I think in terms of pitching complete games.”

This is anathema to the current dogma limiting pitch counts, which has rendered complete games a rarity. Nowadays, pitchers rarely complete games (only six MLB pitchers completed four games last season), and throwing more than 110 pitches a game is considered Herculean. Not surprisingly, Hamburger does not subscribe to this philosophy.

“I am completely against pitch counts,” he says. “I should be able to throw 140 pitches if needed.”

Through his first 12 starts, Hamburger has pitched four complete games and thrown 120 pitches or more in four outings.

While many pitchers spend hours lifting weights, believing bigger is better, Hamburger attributes his arm stamina to stretching and Visnaya yoga, which he started practicing seriously post-Hazelden. He’s lucky that he has never had a serious arm injury. “You can’t break Gumby,” he likes to say.

It’s not that he sees himself as invincible. He’s suffered enough to know that’s not the case. It’s just that he believes he can make it back to the big leagues on his terms.

They say abusing drugs stunts emotional growth, and that recovery allows addicts to resume growing up. Contrasting the Mark Hamburger of 2013, during his last stint with the Saints, with the Mark Hamburger of today provides a measure of newfound maturity.

“He’s done a lot of growing up,” says pitching coach Ligtenberg. “Three years ago, he was not as polished. This year, he is locating his fastball inside and outside. He is taking it more seriously. He’s prepared for his starts. He’s not just throwing hard but has become more of a pitcher, picking his spots, changing speed.”

The maturity has manifested itself in his personal life as well. Steve Hamburger says he and his wife enjoy having Mark at home now.

“He’s gotten a little bit of the beast out of him,” Steve says. “I don’t have to worry about him any more.”

The kid whom his dad says used to move at 100 mph has learned to appreciate life in the slow lane. Mark prefers cooking food over a bonfire, washing clothes on an old-fashioned washboard, and queuing up LPs on a record player instead of listening to music through his phone. “I like the slower life,” he says. “It creates a mindful practice.”

He has been spending his downtime working with his brother Paul, a master welder and carpenter, on restoring a 1960 camper. He plans to move out of his parents’ house at the end of the season and take up residency in the camper, breaking it in with a trip up to the North Shore. “I’m going to practice tiny living,” he says.

Mark’s interactions with fans also show how he’s matured. In Rochester, he sang the national anthem on Fan Appreciation Night, the Red Wings’ final home game of the season. Afterward, the fans saluted him with a standing ovation.

Another night in Rochester, he signed autographs for 45 minutes while fans waited for the start of a postgame concert. “Nobody else does this,” one Red Wings fan told him. “We really appreciate this.”

At CHS Field, Hamburger catches the ceremonial pitches on nights when he’s not scheduled to start, returning the ball with a hug to the honorary pitcher.

He runs the errand of delivering a batting helmet to the kid sitting with the ball boy down the right field line. But instead of trotting back to his teammates, he squats to chat with the kid for a few minutes. On his way back between innings, he pauses to greet fans he recognizes in the front row.

At the end of the game, when Saints players toss oversized stuffed balls into the stands, Hamburger points to a fan behind the protective screen above the dugout and throws the ball playfully toward him, knowing it will bounce back off the screen. He laughs, then goes around the screen and flips the souvenir to the fan.

Maturity has also altered his ambition. When he was younger, big money was the draw. “The goal used to be about going to the big leagues and getting your pension,” he says. No longer. “I’ve let go of that. Being a millionaire now has no allure.”

If it were about the money, he could easily be earning more than his current $2,000-a-month salary pitching in Korea or Mexico, but he prefers playing close to home before family and friends. He ticks off other perks: “My chiropractor, my masseuse, a great facility, a front office who cares about us. They promote being silly.”

It’s all part of the evolution of Mark Hamburger.

Shortly after 7 p.m. on a Friday night, a perfect summer evening for baseball, Hamburger stands behind the mound, facing the flag in center field, about to go for his 10th straight victory. Flanked by two Little Leaguers, Hamburger sways a few times back and forth at the hips, takes two deep breaths, and stands still. One of the Little Leaguers turns to him and says, “You’re going to have a perfect game.”

After the first batter singles to right, the second batter singles to left, the third batter advances the lead runner with a long fly, and the fourth batter bloops a single, driving home Fargo-Moorhead’s first run, Hamburger has thrown a dozen pitches to four batters and is down 1-0 with two runners on and only one out. “That kid was so off,” he thinks.

Privately, he had known it was going to be a tough night. He has an open cut on the inside of his right index finger — right where he grips his split-finger fastball, his best pitch. “It was a test,” he would say afterward.

He passed. He induces the next batter to ground into a double play. Once his team has evened the score, he starts the second by striking out the first two batters on seven pitches and retires the third on a fly to left field.

When Hamburger jogs out to the mound to start an inning, his hair flapping up and down, he sometimes steps on the chalked first-base line. Many ballplayers consider that bad luck and hop exaggeratedly over the chalk, but Hamburger professes not to have any superstitions.

“Absolutely none,” he says. Save one. On days he pitches, he brings a two-sided baseball card with him to the ballpark, with a picture of Satchel Paige on one side and Sister Rosalind, the Saints’ nun masseuse, on the other. It’s stashed in his locker at the moment.

He watches his team’s at-bats from the top step of the dugout, his hat off, his arms draped over the railing. When a line drive to left with the bases loaded scores two runs, he skips happily over to the dugout entrance to congratulate the two teammates.

After his catcher Tony Caldwell hits a two-run homer, Hamburger dances over to the entrance and organizes his teammates to form a canopy by standing opposite one another and clasping hands for Caldwell to pass under. Four innings later, he choreographs a slow-motion run from the opposite end of the dugout to celebrate Willie Argo’s two-run homer that stretches his lead to 10-3.

On the mound, Hamburger works quickly and efficiently. He finishes his delivery with his chest tucked toward the ground and his right leg poking into the sky.

But he seems distracted by his cap. He takes it off several times and studies it, as though he’s wondering whether he has accidentally grabbed a teammate’s cap that doesn’t fit quite right.

I ask him about this after the game. “Wait a minute, let me see if he’s still there,” he says and ducks back to his locker. He returns with his hat and shows me a green beetle clinging to the back. “I thought he might have fallen off after I threw a fastball, but he was still there. I had to keep checking.

“I named him Sammy Sosa, but after that guy homered, I figured that wasn’t working so I renamed him Randy,” after Randy Johnson, the Hall of Fame pitcher whom he idolized growing up.

That settled his luck. The beetle hung on for the ride through the eighth inning.

That’s when it stops looking easy for Hamburger. He gives up a home run, then hits a batter with a wild pitch. (When the batter jogs to first, Hamburger apologizes.)

The next batter fouls off three pitches before Hamburger finally gets him to miss, which ends his night. He’s thrown 120 pitches, 85 for strikes, fanned eight batters, walked none, and consistently fired his fastball in the low 90s.

He leaves with the score 10-4, which is how it stays to record his 10th consecutive win.

Afterward, the lack of media in the clubhouse reminds Hamburger of the humble level of his success. Only one reporter (yours truly) and two college students enrolled in a sports journalism internship ask to talk to him.

He graciously asks the students their names and shakes their hands. He patiently answers their questions. But he deflects mine about the injury to his cut finger with a laugh. Won’t tell me how it happened. Which means there must be a good story there, hinting that I’ve only scratched the surface with him.

In the dugout on the first day we met, Hamburger smiled when I asked him about being able to pitch again in the major leagues. He likes the idea of it, but is just not sure how or if it will happen.

“The dream is evolving as I go,” he says. “Nine years ago, the dream was about getting to the majors. The goal now is to be present. Last time I was here, I was picking up the pieces. Now I’m whole.”

That’s huge for him, the chance to play whole in his hometown for a first-place team that sells out night after night. Never mind that the stadium fills with 7,410 instead of 45,000 fans. Playing for the Saints is in keeping with his preference for the slower life.

“The competition level is different, sure, but we play awesome baseball here before packed crowds,” he says. “I’d like to consider this a big league experience — without the private jet.”

© John Rosengren