For Roderick Sewell, the first double above-the-knee amputee to complete the Ironman World Championship, the road to Kona began at a trolley stop in San Diego one morning when he was eight years old. He and his mom had just left a homeless shelter where they had spent the night. They watched a woman hustling toward them across the tracks. “I thought she was crazy for dodging two trains,” Sewell, now 27, recalls with a laugh.

But Marla Knox wasn’t crazy. A recreation therapist involved with Disabled Sports USA, she simply wanted to tell the boy and his mother about opportunities the organization offered people with disabilities to develop independence, confidence, and fitness through athletic involvement.

Sewell was born without tibias in both legs. Knowing they would never develop properly, his mom, Marian Jackson, made the difficult decision to have both legs amputated above the knee before he was two years old. Several years later, after working for the Navy, the single mother decided to apply for unemployment as the best chance for her son to receive the medical assistance he needed. The next four years, beginning when Sewell was eight, they bounced in and out of homeless shelters.

That made the invitation to check out Disabled Sports especially timely. Sewell enjoyed the sampling of handcycling, wheelchair basketball and other activities. He had tried skateboarding and clomping around with Tupperware containers on his stumps, but this opened a door of new possibilities. Soon he connected with the San Diego-based Challenged Athletes Foundation, which provides funding to give disabled individuals the chance to compete in sports. The organization outfitted Sewell with his first pair of running blades at age 10. “They let me know I could live a healthy, active lifestyle,” Sewell says. “They gave me the chance to learn what I could do.”

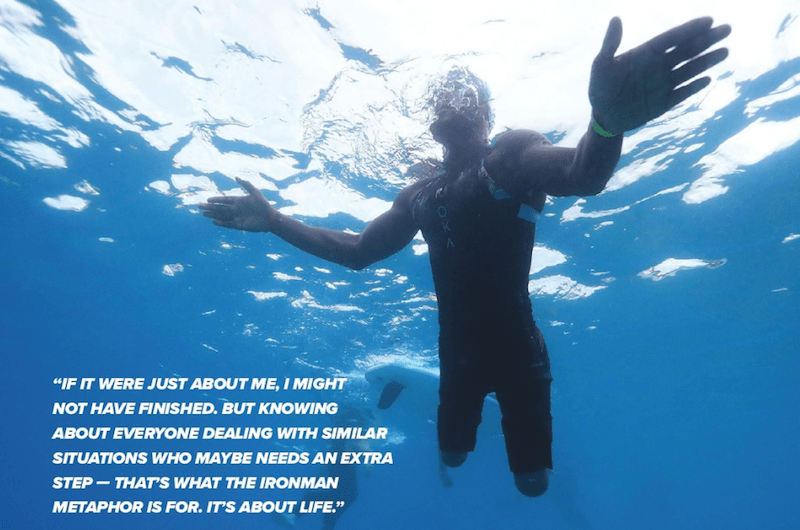

That included learning to swim, something he thought he would never do. “I was terrified of water,” he says. “I didn’t know how I would support myself [without legs].”

Alan Voisard, a CAF swim coach, showed him how at the mission Valley YMCA, first positioning Sewell on a surfboard, paddling with his arms, then paddling without the board. “He helped me relax,” Sewell says. “Once I overcame my fear, I fell in love with swimming.”

He had dabbled in competition, but it wasn’t until he traveled to Beijing in 2008 to watch fellow double above-the-knee amputee Rudy Garcia-Tolson–who had befriended Sewell at his first CAF event–win gold in the 200-meter individual medley that Sewell wanted to compete at a higher level. Six years later–after moving to Alabama with his mom and completing his bachelor degree in public communication at the University of North Alabama–Sewell won gold in the 100-meter breast stroke and bronze in the 200-meter relay at the Pan Pacific Para championship. The next year, he again won gold in the 100-meter breaststroke at the CanAm Para championship.

Sewell got his first taste of the triathlon in April 2019, when he did the swim and run segments on a relay team at the Ironman 70.3 Oceanside. Afterward, Bob Babbitt, cofounder of CAF, which had supported Sewell with prostheses, a handcycle, travel grants, and race fees, asked him, “Would you do Kona if you had the chance?”

Helping people in the same situation, giving kids legs and wheelchairs, letting them live a new life they didn’t know was possible–being able to do that is a good feeling for sure.

Sewell’s first thought was no. He had never completed a triathlon of any distance, let alone an Ironman. He had heard Garcia-Tolson’s horror stories from his attempt in 2009 when he missed the cutoff by eight minutes in the cycling segment. Garcia-Tolson did complete the Arizona Ironman six weeks later, and Scott Rigsby, a double amputee below-the-knee finished Kona in 2007, but no one like Sewell–a double above-the-knee amputee–had ever finished the Ironman World Championship. “Kona was not on my mind,” Sewell says. “I never thought I would ever do it.”

Then in August, when Sewell attended Ironman’s IPO celebration in New York, Ironman CEO Andrew Messick publicly praised Sewell for all he had done to inspire others before surprising him with an invitation to Kona. “In front of everyone with the cameras on, even if you wanted to say no, you can’t say no,” Sewell says.

So he graciously accepted and got serious about his training, especially on his handcycle, gradually building up his strength on increasingly longer rides. Two weeks before Kona, he did his first full triathlon, the Mighty Montauk Half Ironman. By the time he reached Kailua Bay on October 12, Sewell felt ready, physically and mentally.

But Kona has crushed many a triathlete’s ambitions. Once on the course, he feared it might decimate his. Choppy water during the swim, his strongest event, knocked him nauseous. On the bike leg, his weakest event, winds along the course gusted up to 50 miles an hour. Starting up Hawi, he saw the wind flip a fellow competitor off his bike. “I knew I couldn’t stop and had to keep a steady pace,” he says.

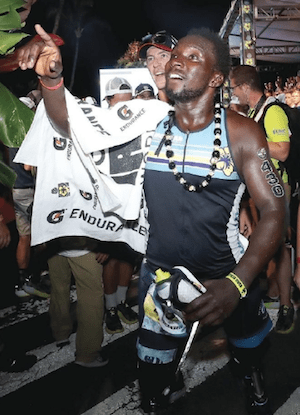

Even when the effort climbing Hawi made him vomit near mile 37, he kept his wheels moving. He started the run strong the first ten miles but had to walk the eleventh to gather his strength. He ran to mile 16, walked another mile, ran to mile 20, but had to walk again. “There were a lot of times I wanted to stop,” Sewell admits.

Yet the thought of all those watching, looking to him for inspiration, kept him going. “If it were just about me, I might not have finished,” he says. “But knowing about everyone dealing with similar situations who maybe needs an extra step–that’s what the Ironman metaphor is for. It’s about life.”

While Sewell battled the course, his mom faced her own struggle on the sidelines. She had not realized how difficult and demanding Kona was. She had endured the Ironman equivalent of stress in her life raising a child with special needs. Her family had criticized her decisions. Child welfare workers had threatened to take away her only child. Watching her son on the course recycled all that.

But Sewell knew the depths of his mother’s reserves. “She was strong before I came around,” he says. “I definitely have a lot of her in me. She supplies me with my willpower.”

He managed to draw upon that to run the final miles across the finish line and into his mom’s arms, where he collapsed and she wept. Tears pooled with relief, joy, and pride.

Others waiting for him at the finish line–16:26:59 after he started–included Garcia-Tolson, Babbitt, and Sarah Hartmann and Brett Hawley of the Ironman Foundation.

Back in Brooklyn, where Sewell now lives, he has started training for the cycling event at the 2020 Paralympics in Tokyo. He manages an endurance training studio, coaches swimmers, gives motivational speeches, and serves as a CAF ambassador–metaphorically running across trolley tracks to encourage others with physical disabilities to live an active, healthy life. All of which has brought him happiness. “Helping people in the same situation, giving kids legs and wheelchairs, letting them live a new life they didn’t know was possible–being able to do that is a good feeling for sure,” Sewell says.

© John Rosengren