He woke before the sun crept above the mountains in the clear, cloudless sky and knew it had to be done. He tucked his feet into the moccasins he used as slippers, fastened his plaid bathrobe over his blue pajamas, and stepped past his wife’s bedroom, where Mary lay sleeping. He found the keys on the window ledge above the kitchen sink where she had left them. He unlocked the door to the basement storage room, selected his favorite shotgun–a Scott double-barreled 12-gauge–pocketed a couple of shells, closed the door, and shut off the lights. He climbed the basement stairs, more effort than they once were, and passed through the living room to the 5- by 7-foot foyer with oak-paneled walls. He slid a shell into each barrel, snapped the gun shut, and secured the stock against the linoleum floor.

Ernest Hemingway had spent the majority of his last seven months being treated for depression at the Mayo Clinic during two separate stays, in the winter and spring of 1960 and 1961. He had been delusional, depressed, paranoid, and suicidal.

But Mayo’s chief of psychiatry had concluded in late June that Hemingway “had recovered sufficiently from his depression to warrant” his discharge.

Less than a week later, on July 2, 1961, Hemingway leaned over the Scott shotgun, gripped the metal in his mouth, and fired both barrels.

The news went viral in the way it did in those days: over the wire services and onto the front pages of newspapers across the world. President John F. Kennedy, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and former Mayo patient himself, remarked, “Few Americans had a greater impact on the emotions and attitude of the American people than Ernest Hemingway. . . .he almost single-handedly transformed the literature and ways of thought of men and women in every country in the world.”

That may have been a stroke of hyperbole–every country?–but it bespoke the stature of the man and his work. Hemingway was an international treasure whose wife had entrusted his care to the premier medical health care professionals of the day. Yet they failed him.

They had locked him in the psych ward but allowed him to roam about town; diagnosed him as suicidal yet taken him trap shooting; acknowledged his alcoholism then allowed him to drink. Even by the standards of the day, the treatment was questionable. At times, they behaved toward him more as a friend than a patient. Such was the power of Hemingway’s charisma, which could intoxicate those in his orbit.

Soon after summer vacation started, Lynne Bartholomew had been climbing trees and playing baseball in the park with her friend Franny Butt. Afterward, the pair of 12-year-old tomboys stopped at Franny’s house, where they found her father, Dr. Hugh Butt, standing in the doorway alongside a tall, bearded man.

“Linus,” said Dr. Butt, using her nickname, “this is Papa.”

The man reached out a big, strong hand and shook hers.

An aura hung about him, but she did not know who he was.

Later, at home, she told her mother she had met a bearded man named Papa at the Butts’ house. Her mother gasped. Ernest Hemingway was one of her favorite authors. She considered her daughter’s cutoff shorts and T-shirt. “Dressed like that?”

“Yup,” Lynne said. “He didn’t mind.”

By the summer of 1961, despite the Mayo Clinic’s reputation for guarding patient privacy, Hemingway’s presence in Rochester had animated the sleepy hospital town of 41,000–even if he was merely a shadow of himself.

There had been other celebrity patients–Lou Gehrig, Ed Sullivan, Lyndon Johnson, JFK as a teenager–but Ernest Hemingway was the Clinic’s most famous. His taut, direct style in short stories and novels such as The Sun Also Rises, For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea had transformed American literature and won him the Nobel Prize in Literature. His life had become legend. He was a handsome ladies’ man who married four times and indulged in multiple mistresses. He was a man’s man: a boxer, drinker, and gambler. He had immersed himself in the Great War, the Spanish Civil War, and the Second World War. He hunted big game in Africa; deep-sea fished from his yacht; and befriended generals, movie stars, bullfighters, and artists.

But his hard living–including nearly a dozen concussions–had ground down his body and mind. During the summer of 1960 and into the fall, the 61-year-old writer became increasingly paranoid, deluded, and depressed. The worries caused him to lose weight, interrupted his sleep, and spiked his blood pressure. Once robust and athletic, he had become frail and thin. He talked more insistently of suicide, an obsession that dated back to 1928, when his father shot himself. It all nearly drove Mary, his fourth wife, mad.

They had met in 1944, when both landed in London, covering the war as journalists. Nine years younger, Mary Welsh was born in Walker, Minnesota, and raised in Bemidji. Small and slim, she wore her blond hair short and could hold her own against him fishing and hunting, drinking and screwing. A week after they met, he proposed, despite the fact both were married to other people. “He was such an impulsive man,” she told a journalist years later.

With her husband’s mental condition crumbling in the fall of 1960, Mary sought the advice of George Saviers, the local doctor where they lived in Ketchum, Idaho, and one of Hemingway’s good friends. Hemingway refused the suggestion to check into the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas. “They’ll say I’m losing my marbles,” he complained.

He eventually agreed to Mayo. Then as now, the Mayo Clinic enjoyed a reputation as the world’s finest and most famous medical center. He could go there under the auspices of treatment for his high blood pressure and, tucked away in the boondocks, avoid scrutiny by the press.

On November 30, 1960, Saviers flew with him from nearby Hailey to Rochester in a four-seat Piper cub piloted by Larry Johnson of Johnson’s Flying Service. The hospital admitted Hemingway secretly, under Saviers’s name, and placed him in a private corner room on the first floor of Saint Marys Hospital, concealed among rheumatism and arthritis patients. Nonetheless, as Charles Mayo observed in his autobiography, that location didn’t stop curious hospital staff from streaming by to glimpse the famous patient.

Mary followed by train, plane and bus, checking into Room 1060 at the Kahler Hotel as Mrs. George Saviers.

Mayo Clinic assigned two of its top doctors to treat Hemingway, the internist Hugh Butt and the psychiatrist Howard Rome, both 50 years old. Butt had distinguished himself with the discovery that vitamin K could save jaundice patients from fatal internal bleeding. Rome, chief of psychiatry, loved literature and advocated reading Dostoyevsky to understand psychiatric conditions.

In his initial examination (which he later summarized in a letter), Butt diagnosed Hemingway with a mild case of diabetes and an enlarged liver that suggested hemochromatosis, a rare hereditary condition that increases iron absorption. Hemochromatosis is sometimes associated with diabetes, memory loss, and depression, symptoms Hemingway presented. The only way to confirm it involved a liver biopsy, but that required surgery. Butt opted not to take the risk, most likely attributing Hemingway’s swollen liver to decades of daily drinking.

Both Butt and Rome believed Serpasil, one of the medications Hemingway had been taking for his high blood pressure, may have caused his “depression, agitation and tension”—perceived side effects of the drug. They took him off it and off the Ritalin he had been prescribed to counteract the Serpasil-induced depression. Rome instead prescribed Librium, a then-new sedative that had yielded positive results in reducing anxiety and tension in alcoholics.

Rome also administered electroconvulsive therapy. At a time when the mentally ill were warehoused in asylums, Mayo stood out as a pioneer in believing these patients could be cured in a hospital setting. Rome once described himself in an interview with the Mayo Alumnus as “an unregenerate optimist.”

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) sends electric currents through the brain to trigger a brief seizure, which causes the body to jerk uncontrollably for about 40 seconds. With antidepressants and antipsychotics in their infancy, it was the most effective treatment for severe depression, yielding a reported 90 percent cure rate. (Indeed, Mayo and other medical facilities still administer ECT, though no one yet knows exactly how it works on the brain’s circuitry.) A typical course ran 10 to 12 treatments, administered twice a week.

Despite the violence of the procedure, Hemingway may not have resisted. Three years earlier, he had urged his son Gregory to get ECT after seeing the positive effects his older son Patrick realized from the treatment several years previous. Papa Hemingway is believed to have received 15 treatments through December and into early January, each of which left his mind temporarily fogged.

Days he didn’t get shocked, Hemingway roamed the hospital, run by the Sisters of Saint Francis, often stopping in at the first-floor office of Sr. Lauren Weinandt, assistant to the administrative director, to sit and chat. One day he gave her a 6-inch decorative Christmas tree for her desk. She knew he was there to be treated for depression, “but he was always up when he talked to me,” she told me.

Sometimes he walked up the hill behind Saint Marys–nicknamed “Pill Hill” because many doctors lived there–to the Butts’ stucco house on 7th Street SW. Butt had invited him to stop in whenever he wished to sit in the bright sunroom, browse his library, or simply rest. “He felt like he had a little oasis in Rochester during his shock treatments,” Franny Butt told me.

Hemingway had adopted Dr. Butt as one of his pals, and the two became good friends. One time, Franny’s dad told her, “Hit Papa in the stomach.” Hemingway smiled at her: It was all right, go ahead, this was a game he played. Franny complied. “His stomach was like iron,” she says.

Butt invited the Hemingways to Christmas dinner. Nervous about hosting the famous author, Mary Butt prepared a buche de Noel, needing three tries to get it right. Dr. Butt served one of the best wines from his cellar. The Hemingways entertained the family with songs in French and Italian.

Despite the picture of happiness Hemingway projected, his wife Mary had been distraught on Christmas Eve. “After 24 days and nine electric shock treatments, he seemed to me today to be almost as disturbed, disjointed mentally as he was when we came here,” she wrote in a letter to herself that night. She noted some improvement: “He no longer insists that an FBI agent is hidden behind the door of the bathroom with a tape recorder.”

Yet the preponderance of his delusions, paranoia, and depression persisted. She saw him “cutting off sunshine, gaiety, dancing, delicacy, love, affection, friends, and all the big bright world.”

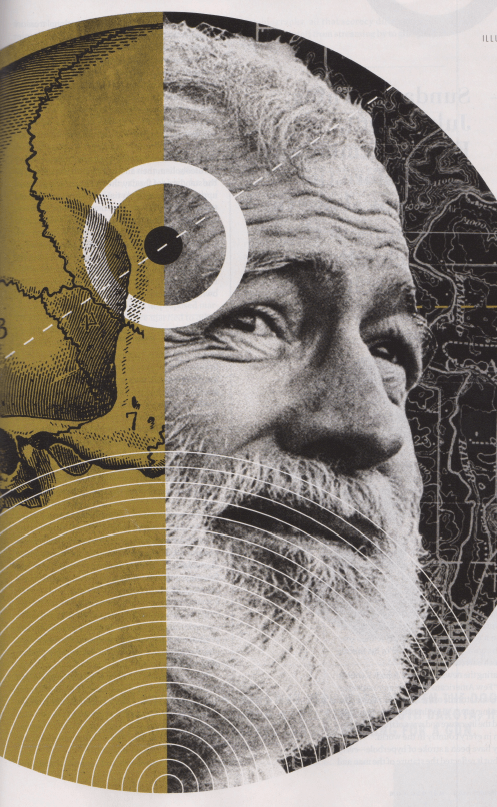

Ernest Hemingway and Mary Welsh Hemingway (see here in 1946) checked into the Mayo using assumed names, for privacy.

On the flight to Rochester, Hemingway struggled to open the door and jump out of the plane. During a fuel stop in South Dakota, he rummaged through parked cars, searching for a gun.

By early January, however, Rome believed Hemingway had shown enough progress to discontinue the shock treatments. Sunday, January 8, the doctors hosted a luncheon with Hemingway as the guest of honor. Afterward, Butt took him trap shooting at an abandoned quarry near Mayowood. Hemingway, an excellent shot, picked off 27 consecutive clay pigeons.

On January 10, while Mary visited relatives in Bemidji, the news broke nationally and internationally that Hemingway was a patient at Mayo. The following morning, the Clinic uncharacteristically released a statement acknowledging Hemingway doctors at Saint Marys were treating him for hypertension, with no mention of depression or ECT. The statement added, “It is necessary that his right to privacy be respected and that he have the benefit of rest and quiet.”

The Rochester Post-Bulletin had actually reported the story a month earlier. Reporter Kenneth McCracken was eating dinner at a restaurant when he got a tip about Hemingway at Saint Marys. He hurried over to the hospital, slipped by the nurses, asked another patient which room was Hemingway’s, and walked past the “No Visitors” sign into Room 1-126. Hemingway swore and flung a dinner tray at McCracken. A nurse hustled him out, but McCracken had confirmed the rumor.

When the story went national, strangers sent Hemingway letters and gifts–a scapular, a rosary, a poem. Acquaintances dating back to the Great War called to wish a speedy recovery. Journalists circled like predators.

The Mayo press officer, Jim Eckman, passed along messages to Hemingway and fended off the press. “This is the day this Old Man wishes he was Far Out to Sea, Boy,” he quipped.

A day later, Gary Sukow reported in the Rochester Post-Bulletin that Hemingway was receiving electroshock treatment, without confirmation from Mayo. Hemingway fretted that the story would go out over the wire services, but Eckman prevented it.

Hemingway still feared the FBI. He had called local authorities to turn himself in, “but they didn’t know about the rap,” he told his friend Aaron Hotchner. Rome consulted the bureau office in Minneapolis, asking permission to assure his patient the FBI took no umbrage with his patient for registering under a false name. Even then, Hemingway was only temporarily appeased.

In the days after his stay at Mayo was disclosed, locals spotted Hemingway about town, sitting with Mary at a window table at the Kahler Hotel coffee shop downtown and often walking along a country road in his houndstooth cap.

He found energy to answer mail that had accumulated. Seeing the exercise as therapeutic, Rome offered the services of his long-time secretary, Marie McQuarrie. She typed for hours while Hemingway dictated a flurry of letters from his bed that frequently mentioned his eagerness to resume work on a memoir about Paris (published posthumously as A Moveable Feast). He also reported his blood pressure had stabilized, yet complained it was difficult for a heavyweight like him to keep his weight down to the 175 pounds recommended by his doctors.

To thank Mrs. McQuarrie, he gave her a signed copy of For Whom the Bell Tolls and a signed copy of The Old Man and the Sea for her daughter. Patricia, a seventh grader at the time, excitedly showed the book to her classmates at Rochester Central Junior High. “I told everyone I knew she was working for him,” Patricia said of her mom. After English class, she put the book in her locker, but someone stole it. She was crushed. “I feel really bad to this day,” she told me.

President-elect Kennedy invited the Hemingways to attend his inauguration on January 20, 1961, but Hemingway had to send his regrets. He watched the ceremony on television with Mary. Afterward, he wrote several drafts of congratulations, eventually cabling, “It is a good thing to have a brave man as our President” and “how beautiful we thought Mrs. Kennedy was.”

On January 22, Hemingway left Saint Marys and Larry Johnson shuttled him and Mary back to Ketchum in his plane. In his discharge instructions, Butt stipulated that Hemingway could drink wine, but no more than a liter a day.

Rome wrote, “It is my judgment that you have fully recovered from this experience and I see no reason to anticipate any further difficulty on this score.”

As a celebrity patient, Hemingway could check himself out of the locked ward at Saint Mary’s Hospital (above). He like to roam the country lanes around Rochester and go trapshooting.

His first day back, Hemingway joked with longtime friends Lloyd and Tillie Arnold–“like the normal Papa,” Tillie observed. He shot trap almost daily with Saviers, who came by ostensibly to check his blood pressure. Hemingway went for 4-mile walks with Mary. But he struggled to write, staring vacantly out the window above his desk.

By late March and into April, he became listless and withdrawn. On April 18, he wrote to his publisher that he had only messed up the Paris memoir and conceded failure. Once again despair consumed him. His moods, which could descend into vicious tirades, tormented Mary. She suggested he return to Mayo.

He confided in Tillie that he had an incurable disease, hinting at suicide. “There’s no other way out for me,” he said. “I am not going back to Rochester where they will lock me up.”

The next morning, April 21, Mary found Hemingway in the oak-paneled front foyer cradling an open shotgun, two shells upright on the windowsill. She sat on a small sofa and tried to talk him down. She did not dare try to wrestle the gun from him, afraid he might shoot her if she did.

When Saviers finally arrived for their noontime trap shoot, he managed to convince Hemingway to come with him to the hospital, where he sedated him. That weekend Saviers arranged for Hemingway’s return to Mayo. Monday morning, Hemingway asked to pick up some fresh clothes at the house. Don Anderson, a husky friend, drove him. At the back door, Hemingway bolted out of the car and through the house. He got a shell in the shotgun before Anderson yanked the barrel and shoved him to the sofa.

On April 25, Larry Johnson once again flew Hemingway, along with Saviers and Anderson, to Rochester. Shortly after takeoff, Hemingway struggled to open the door and jump out of the plane. Saviers and Anderson teamed up to restrain him. They stopped for a minor repair and to refuel in Rapid City, South Dakota. Hemingway searched through tool chests in the hangar and glove compartments of parked cars for a gun. When he couldn’t find one, he headed toward a plane taxiing down the runway, apparently intent on throwing himself into the propellers. But the pilot cut the engine. About three in the afternoon, they finally arrived in Rochester, where Butt met them at the airport.

Rome assigned Hemingway, admitted under his own name, to 6D East, the locked psychiatric ward. Recognizing “classical diagnostic features of an agitated depression: loss of self-esteem, ideas of worthlessness, a searing sense of guilt,” the doctor immediately began an aggressive round of shock treatments, four in the first five days. After the initial three, Hemingway wrote Mary, who had stayed behind, “The treatments made me feel much better than when I was out in Ketchum, but the days and nights are very long.” He rambled about his worries in sloppy penmanship and thrice mentioned how lonesome he was without her.

A week later he wrote to Mary that their whole financial situation seemed hopeless to him, that he could not remember account details, and that the day after a treatment, “My head is buzzing so that I can barely write this.” On May 8, after two more treatments, he wrote her in a letter he didn’t finish, “The electric business knocks all of the addresses out of your head.”

A side effect of ECT includes memory loss, though usually temporary. The confusion deeply troubled Hemingway, who had possessed a near photographic memory. Mary believed Rome thought the shock treatments were more effective than they actually were. Indeed, it is now understood that alcoholics often don’t respond to ECT, and Hemingway was undoubtedly an alcoholic. If, in fact, he was also suffering from undiagnosed dementia, as some suspect, the shock treatments could have worsened his condition.

Such discoveries in the nearly 60 years since Hemingway’s death–along with Mayo’s staunch refusal to release his medical records–have prompted second guessing in medical journals and popular media about his diagnosis and subsequent treatment. One theory posits that the genetic condition hemochromatosis, which Butt had suspected, caused not only Hemingway’s depression and suicide but that of his father, two sisters, brother, and granddaughter–though this now seems unlikely. Others speculate that Hemingway and family members suffered from bipolar disorder–which has also been debunked. Most recently, Andrew Farah, chief of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina Healthcare System, suggested convincingly in his 2017 book Hemingway’s Brain that Hemingway had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and was in the early stages of dementia. Hemingway had endured almost a dozen concussions from his days playing high school football to a car accident in Spain the year before he arrived at Mayo. At that time, though, doctors considered CTE–known as dementia pugilistica–an affliction limited to punch-drunk boxers.

“His death was the result not of medical mismanagement but of medical misunderstanding,” Farah writes. “Hemingway received state of the art psychiatric treatment in 1960 and 1961, but for the wrong illness.”

Through the bars on the windows of his room, Hemingway could see the cafes across 2nd Street SW and a sweeping view of the fields to the north, a vista dominated by the Sisters of Saint Francis’ hilltop, Italian-style monastery. Rome understood the harmful effects prolonged confinement could inflict upon a patient and worried the loss of freedom might be detrimental to Hemingway. So when Hemingway pledged he would not harm himself, Rome relaxed the restrictions. He allowed Hemingway to leave the locked unit as he pleased to go trap shooting, picnic near the Mississippi, and hike the outskirts of town.

Leaving his house early one morning, Anthony J. Bianco Jr., an orthopedic surgeon with the Clinic, was surprised to see his headlights illuminate Hemingway’s familiar white beard along Institute Road. Other times, Hemingway stopped to talk to Bianco’s son Dick when he was mowing the lawn. “He was like a bear, very hairy,” Dick Bianco told me. Farther along, in a house on Balsam Court, Myra Sullivan looked up from the kitchen window one morning when she was peeling potatoes and spotted her literary idol walking by briskly. The sight repeated itself maybe ten times that spring.

Neil Haugerud, former sheriff of neighboring Fillmore County, writes in his memoir, Jailhouse Stories, that one early May afternoon he ran into a friend drinking at the Kahler Hotel lounge with Hemingway, who was slurring his words. The story may or may not be true, but the possibility of it happening points to the unorthodox latitude afforded Hemingway as a patient in a locked psychiatric ward. Even by the standards of the time, which were more lenient than today’s, it was unusual for doctors to grant a patient with an enlarged liver and long history of daily drinking to consume alcohol. It was stranger to put a gun in the hands of a depressed patient who had intended to shoot himself.

Hemingway engaged both Rome and Butt on various occasions in discussions about literature. They were all too willing to have the opportunity to do so with their Nobel Laureate patient. Hemingway’s charisma, even in his depreciated state, may also have personalized and compromised their professional judgment, accounting for some of the unusual privileges they granted him. “They were enamored of his celebrity and his talent,” Anthony J. Bianco III, who is working on a history of the Mayo Clinic, told me. “He sort of bewitched them.”

At the same time, their intimate relationship allowed the doctors to understand their patient’s nature. Aware of Hemingway’s need to be among people, Rome charged Bob Rynearson, one of his young residents, to socialize with the writer. Bob was the son of Edward Rynearson, an endocrinologist at Mayo, a friend of Rome and Butt, and a collector of Hemingway first editions. The younger Rynearson invited Hemingway to Sunday brunch at his parents’ Cape Cod-style house in the Sunny Slopes neighborhood, where deer roamed the lawns. Their house featured Rochester’s first in-ground swimming pool, surrounded by a white fence and grape vines.

“They told us to treat him like family, but I thought there is no way he is like one of us,” Bob’s wife Marjie told me. She avoided him at first, busying herself with brunch preparations in the kitchen. “It made me anxious to think we had a famous person down by the pool.”

That spring, Hemingway became a regular at the Rynearsons’ table and pool, making the mile-and-a half walk from Saint Marys with Bob’s sister Ann, a recreational therapist. He enjoyed splashing in the pool with the children and telling them stories about the war. He shadowboxed poolside with Bob, fists actually connecting with faces on occasion, knuckles bloodied on teeth.

With time, Marjie’s initial intimidation eased. “He was part of the family,” she says. “He was just kind of magical.”

Marjie offered to prepare Hemingway’s favorite meal, green turtle steak. Bob had the meat flown in from Florida. The night of the dinner, Hemingway arrived early and asked if he could do something useful outside. Bob suggested he mow the lawn. A short time later, a neighbor stopped by to fetch a loaf of bread from the communal freezer in the Rynearsons’ garage. She returned home to report, “The Rynearsons have a gardener who looks exactly like Ernest Hemingway.”

The turtle steaks turned out a bit tough, but Marjie redeemed herself another night with a pheasant dinner that “delighted” Hemingway. He gave Marjie and Bob a copy of The Old Man and the Sea inscribed, “Here’s hoping we can fish together some time. Your old sparring partner, Ernest Hemingway.” At 9 pm a driver came to return the patient to his locked room at the hospital.

Mary visited in May. She later recounted in her memoir How It Was how over dinner Hemingway accused her of seeking to have him arrested and having him held hostage in the hospital. “You think as long as you can keep me getting electric shocks, I’d be happy,” he said.

Concerned that the treatment at Mayo was not curbing his paranoia and depression, she consulted a psychiatrist in New York for a second opinion and at his suggestion toured the Institute for Living in Hartford. She asked Rome to transfer her husband there, but he thought Hemingway was showing improvement.

In early June, Aaron Hotchner visited and drove Hemingway out of town for a walk in the woods on a sunny day. The author later detailed the outing in his book Papa Hemingway.

Hemingway was despondent, cataloguing his troubles. He sat on a stone wall. Hotchner confronted him, “Papa, why do you want to kill yourself?”

Because he could no longer write. What Hemingway referred to as “that thing in my head” wouldn’t let him. “Hotch, if I can’t exist on my own terms, then existence is impossible,” he said.

Mid-June, Rome informed Mary that her husband’s sexual drive had returned and suggested a conjugal visit. She arrived around June 21, but the assignation ultimately proved “entirely unsatisfactory to either of us,” she wrote in her memoir. Two days later Rome asked Mary to meet him in his office. She was surprised to see her husband dressed in street clothes and “grinning like a Cheshire cat.”

The doctor told her Hemingway was ready to go back home. Rome believed his best chance at recovery lay in being free to write. She disagreed but figured it futile to argue. “I realized that he had charmed and deceived Dr. Rome to the conclusion that he was sane,” Mary wrote.

Their friend George Brown flew out from New York to drive the couple back to Ketchum in a rented two-door Buick. They left Rochester on June 26. It took five days to make the 1,786-mile drive, because Hemingway insisted they stop early each afternoon, fearing they wouldn’t find a motel room if they drove longer.

Saturday, July 1, Hemingway ate his last meal at the Christiana Restaurant in Ketchum–Christy’s, he called it–with his wife and Brown. They sat in his favorite corner booth, table five. He ordered New York strip steak, rare, and a French wine, probably his preferred Chateau Neuf du Pape. He became distracted by a couple of men at a small table farther back. The waitress told him they were a couple of salesmen from Twin Falls, but he suspected they were FBI agents and remained agitated by their presence.

Afterward, Brown went to sleep in the cinder-block guest house off the kitchen. In Mary’s telling, while they got ready for bed, she sang an Italian folksong and her husband joined in from his bedroom, then in a “warm and friendly” voice said his last words to her, “Good night, my kitten.” She would also maintain for five years that his death had been an accident.

Mary found him. Crumpled at the foot of the stairs. After the shotgun blast had destroyed him.

When he heard the news on July 2 from Butt, Howard Rome tried to call Mary but could not reach her, so he wrote a two-page letter. He tried to assure her that his decision to release Hemingway had been his, not the patient’s, because he had wanted to spare him the “corrosive deteriorating effects of” confinement in the hospital. In tight, even script, Rome expressed his sympathy and his regret that he could not have done more, “My sorrow is at the loss of such an unusual man, a complex of paradoxes which made him the genius he was at capturing the spirit of a whole generation because he personally epitomized its conflicts and contradictions, its anxiety and courage.”

Mary was not mollified. In the weeks afterward, she considered suing Mayo, holding the Clinic—and Rome in particular—liable for her husband’s death.

But mostly she felt tortured by her own complicity. She had not pushed him to go to the Hartford institute. She had assented to Rome’s discharge. She had locked up his shotguns yet left the keys on the kitchen windowsill.

Three months later, she wrote Rome, lamenting, What more could I have done?

He replied with a typed, single-spaced, four-page letter, reminiscing almost fondly about his many conversations with Hemingway about suicide, honor, fears, and the desire to be in control. He hinted at his guilt and remorse, “I was wrong about the risk and the loss is irreparable for you and me and many others.”

But mostly he justified his treatment and final decision for discharge–irrelevant of the outcome–with words that could hardly have reassured the widow in her grief and guilt, “I feel sure that had I to do it over again today with the information I had, I would do again as I did then.”

© John Rosengren