On Oct. 7, 1965, the day after the Minnesota Twins had defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers in Game 1 of the World Series, a 28-year-old Hasidic rabbi named Moshe Feller approached the desk clerk at the St. Paul Hotel and told him he wanted to speak with Sandy Koufax.

The clerk considered the bearded man in the black hat and sidelocks before him. Like everyone else, he surely knew that Koufax had not pitched Game 1 because it fell on Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, and he must have figured this man was the pitcher’s rabbi. He gave him the phone number to Koufax’s room.

Koufax answered. Rabbi Feller told him what he had done was remarkable, putting religion before his career, and that as a result more people had not gone to work and more children had not gone to school to observe the holiday. He said he wanted to present Koufax with a pair of tefillin, scrolls of scripture worn by Jewish men during weekday prayers.

Koufax invited the rabbi up to his room on the eighth floor.

In Rabbi Feller’s account, he told Koufax he was proud of him for “the greatest act of dedication to our Jewish values that had even been done publicly” and presented him with the tefillin, which he said Koufax took out of their velvet box and handled reverently.

Whether or not such a meeting actually occurred—Koufax, who is now 79, did not respond to requests for comment for this article—Rabbi Feller’s story speaks to the powerful impact Koufax’s decision had on American Jews, both then and now, 50 years later. “It’s something that’s engraved on every Jew’s mind,” says Rabbi Feller, now 78. “More Jews know Sandy Koufax than Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.”

Yet with another Yom Kippur having arrived at sundown on Tuesday, there remains mystery to the story. The few times that Koufax has explained his decision not to pitch that first game of the ’65 Series, he has claimed it was routine, that he always observed the High Holy Days by not pitching. In his eponymous autobiography published the following year, he wrote, “There was never any decision to make … because there was never any possibility that I would pitch. Yom Kippur is the holiest day of the Jewish religion. The club knows I don’t work that day.”

In the 2010 documentary film Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story, Koufax said, “I had taken Yom Kippur off for 10 years. It was just something I’d always done with respect.” He repeated that rationale in a 2014 interview with the newspaper the Jewish Week.

It’s not that simple. In 1960, Koufax pitched two innings of scoreless relief on Oct. 1, the day of Yom Kippur, not long after the holiday ended at sundown, in an otherwise forgettable loss to the Cubs on the next-to-last day of the season with the Dodgers 13 games out of first place. The following year, Koufax started for Los Angeles on Sept. 20, with the first pitch coming mere minutes after sundown ended on Yom Kippur. He threw 205 pitches that night and went all 13 innings to beat the Cubs, even though the Dodgers were again out of contention for the pennant. For both games he showed up at work before the holiday—and its restrictions—ended.

When he announced his intention not to pitch Game 1 the week before the 1965 Series, Koufax said he had not suited up for World Series games in the past when they fell on Yom Kippur. But that was because it had never been an issue; the holiday had never fallen on a game day in the four previous years that the Dodgers appeared in the World Series when Koufax was part of the team (1955 and ’56 with Brooklyn and ’59 and ’63 after the franchise moved to Los Angeles).

So why, in 1965, did he defer to his religion, when he hadn’t in the past?

Most likely because the circumstances had changed. The Sandy Koufax of 1960 and ’61 was not the Sandy Koufax of ’65. During the first six years of his career (1955–60), he had been mediocre, losing more games than he won, and could show up at the ballpark on the High Holy Days without attracting much attention or causing any controversy.

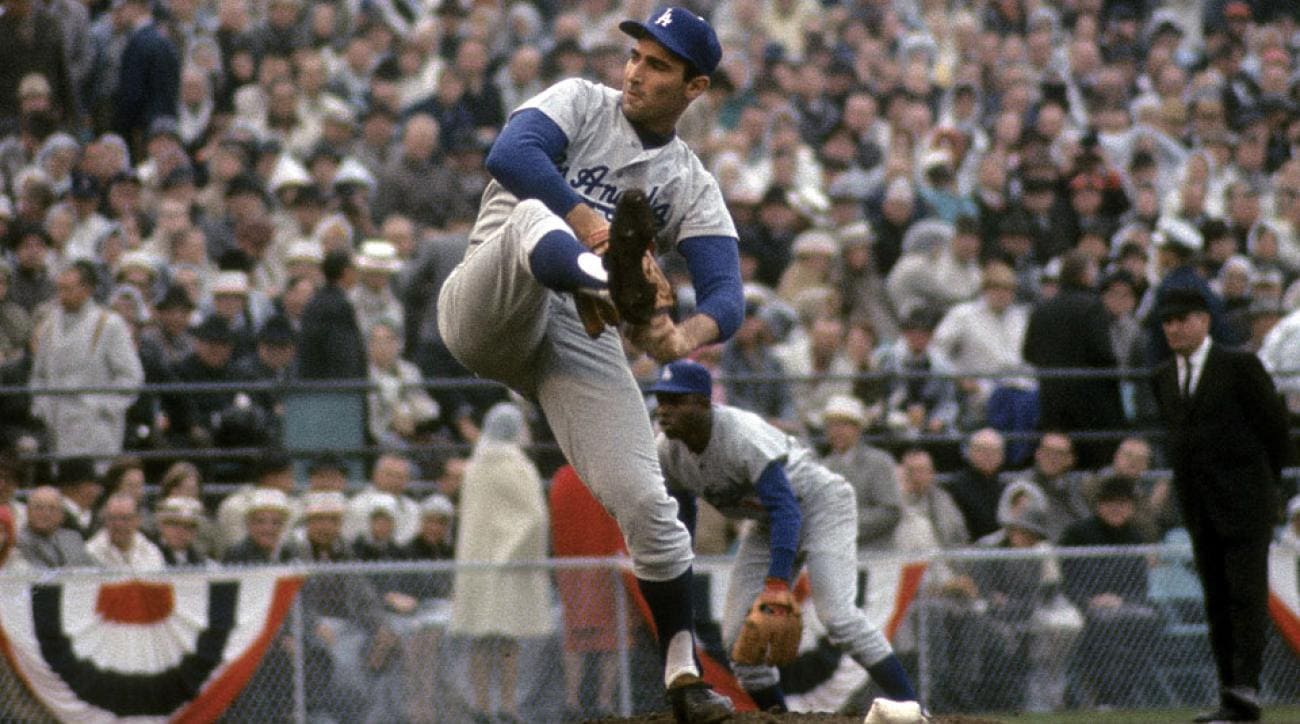

But after he learned not to try to throw as hard as he could—which actually gave his fearsome fastball more movement—that changed. From 1961 to ’65, Koufax went 102–38, posting the National League’s lowest ERA each of the last four seasons, and pitched a no-hitter in each of those years, too, including a perfect game in September 1965. The ’65 season had been the best of his career; he led the majors with 26 wins and a 2.04 ERA and struck out 382 batters, shattering Bob Feller’s single-season record of 348. In an era in which only one pitcher in baseball won the Cy Young Award, Koufax was a unanimous choice, the second time in three years he had won the honor (he would do so again in 1966, his last season).

Koufax was a secular Jew, but he had been raised in the Jewish neighborhood of Bensonhurst, in Brooklyn. He no doubt understood that for him as the marquee star to pitch the first game of the World Series on Yom Kippur would be a blow to his people, a very public repudiation of their traditions. More would be lost—even if he won the game—than gained.

It helped, of course, that he had a very competent replacement in future Hall of Famer Don Drysdale, who had won 23 games that season and two previous World Series starts.

His Dodgers teammates had not pressured Koufax either way, and one told SI recently that they had not considered it a big deal even after Drysdale lost Game 1. (When manager Walt Alston came out to remove Drysdale in the third inning with the Dodgers trailing 7–1, the pitcher is said to have quipped, “I bet you wish I were Jewish, too.”)

“Sandy thought it was the right thing to do—it was,” says Dick Tracewski, then a Dodgers infielder and a former roommate of Koufax’s. “Everybody respected that.”

When Koufax first announced his decision near the end of the regular season, it was a small item in most mainstream newspapers outside of Los Angeles. Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, a Roman Catholic, even joked to reporters, “I’m going to ask the Pope to see what he can do about rain.”

But Koufax’s decision was instantly big news among Jews across the country. Michael Paley was a 13-year-old boy living in suburban Boston when he heard on the radio that Koufax would not pitch on Yom Kippur. The decision became the talk of his block. “It was the beginning of changed feelings about being Jewish in America,” says Paley, now a rabbi and scholar at the Jewish Resource Center of UJA-Federation of New York. “Because of Sandy, we were admired.”

Two decades removed from the horrors of the Holocaust and two years before the Six Day War proved Jewish might, Koufax stood as a symbol of dominance and success. Now he had burnished his reputation as someone willing to honor the traditions of Judaism before all else. Had Koufax been Orthodox or regularly attended services, his observance of Yom Kippur would have been expected. But the fact he had pitched on Yom Kippur in the past and was not especially religious made his decision in 1965 even more significant. It bonded secular Jews with the observant and forged a new cultural identity for American Jews.

“Koufax’s decision says this Jewish piece is a real identity, not just for the Orthodox and the religious people,” Rabbi Paley says. “There is such a thing as American Judaism. We can live in these two cultures. That’s the beginning of having a multicultural identity.”

The morning of Yom Kippur, the St. Paul Pioneer Press reported that Koufax “will attend services today.” The rumor spread that he would do so at Temple of Aaron, a conservative synagogue in St. Paul, which was the closest one to the Dodgers’ hotel.

Steve Shaller, who had just had his bar mitzvah in 1965, remembers waiting outside Temple of Aaron for Koufax to show up before the morning services. “I made my poor father stand out in the drizzle with me to see if he came,” says Shaller, now 63 and a real estate investor. “He didn’t.”

Rabbis throughout the Twin Cities reported that Koufax attended services at their synagogues. Yet none did so as persistently and convincingly as Rabbi Bernie Raskas, who presided at Temple of Aaron and insisted until his death in 2010 that Koufax had attended the morning services there. “He told me that he brought Koufax in through the side door and sat him in front where almost no one saw him,” says David Unowsky, 73, events manager of Subtext Books in St. Paul. “I think if Bernie said it was true, it was probably true. He was a an honorable man.”

Yet Jeremy Fine, associate rabbi at Temple of Aaron, admits that Rabbi Raskas may have fabricated the story to stir up interest in the synagogue or to inspire Jews about their religion. “I wouldn’t put it past him to have made it up,” Rabbi Fine says.

That’s the conclusion Jane Leavy arrived at in her definitive biography, Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy, published in 2002. She is convinced Koufax did not leave his room at the St. Paul Hotel. “Raskas could not have seen him unless he was the room service waiter at midnight [when Koufax would have broken his fast],” Leavy writes.

The only one who knows for certain, of course, is Koufax, and he’s not saying. Famously private, he has never liked to talk about his personal life. As a player, he hid his telephone in the oven so he wouldn’t hear it ring when the press called. In retirement, he has rarely granted interviews. He did not give Leavy one for her biography, or, as mentioned previously, for this article.

The fitting climax to Koufax’s 1965 World Series story occurred when he came back to pitch Game 7 on two days’ rest. He had lost Game 2 in part because the cold, damp weather troubled his arthritic pitching elbow, hampering his control. With warmer weather in Los Angeles for Game 5, he shut out the Twins on four hits to give the Dodgers a 3–2 lead. But when the Twins evened the Series with a win in Game 6, Alston summoned the willing Koufax to pitch the decisive Game 7.

Though his curve failed him that day, Koufax relied on his fastball to strike out 10 batters and shut out Minnesota for the second straight time (which was especially impressive, considering Minnesota had been blanked only three times during the regular season). His complete-game victory secured the World Series for the Dodgers.

In the 50 years since, the story of Koufax in ’65 has been told around dinner tables and in bar mitzvah speeches, impressing each generation that hears it. Red Sox pitcher Craig Breslow first heard the story from his grandparents and later in sermons by his rabbi. “Obviously, as a baseball player, and a Jewish lefthanded pitcher, Koufax’s story resonated with me,” Breslow says. “I admired his courage and his faith.”

Some Jewish ballplayers have followed Koufax’s example by not playing on the High Holy Days of Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur, most notably former outfielder Shawn Green, who consulted Koufax before deciding to sit out a critical game with the NL West title still undecided on Yom Kippur when he played for the Dodgers in 2001. Others, like Breslow, have found different means to balance the commitment to their teams and their religion. “On a number of occasions I have fasted but made myself available to pitch on Yom Kippur,” he says. “I believe there are ways to reconcile one’s commitment to his faith and also to his professional responsibilities.”

At the time, Koufax’s choice was not talked about as often as it is now. When Sports Illustrated named him its Sportsman of the Year for 1965, there was no mention of that decision—or of Yom Kippur or Judaism at all—in the nearly 7,000 word interview with Koufax that ran as the cover story of the Dec. 20 issue. Since then, however, it has taken on a heightened significance, and regardless of how Koufax’s story is observed and what details of it are true, the fact that he sat out Game 1 in deference to his religious tradition makes him a fixture of American history.

“It’s one of the best American Jewish stories we have,” Rabbi Paley says. “He didn’t see the burden of his identity, he saw the possibility of it.”

© John Rosengren