They called him Monster Mike. For the way he threw his sled around on the professional snowmobile circuit and muscled his dirt bike over motocross courses. Arms of steel, gut on fire. Unstoppable. Until that day in December 2008.

He was in Ironwood, Michigan, the second stop on the International Series of Champions tour, what they called the NASCAR of snowmobile racing. On a downhill stretch of the course, Schultz charged from the back of the field, gunning his machine to 40 miles per hour. Then he caught a hole. His snowmobile shimmied from side to side, kicked, and bucked him into the air. He slammed feet first, full force, into the packed snow, flipped, and landed on his back.

The impact so mangled his left knee that he stared down at the sole of his boot. When the EMT arrived and slit open his pant leg, a gallon of blood gushed out. That’s what his wife, a registered nurse, saw when she arrived with a race official: her husband lying in snow stained red. She dropped to her knees by his side. “He was in agony,” Sara Schultz recalls, “making a low, moaning sound.”

Mike was going into shock. She tried to help him focus on his breathing. They loaded him onto a toboggan and transferred him to an ambulance at the base of the hill, but the local hospital in Ironwood (population 5,387) wasn’t equipped to handle such trauma. They needed to get him somewhere that could. Which meant Duluth, 110 miles away. They couldn’t airlift him because of an advancing snowstorm, so they went by ambulance, more than a two-hour drive, all the while Mike grinding his teeth against the pain and his blood pressure dipping so low they couldn’t give him medication. Worse, he kept bleeding.

By the time he got to St. Mary’s Hospital, Schultz had gone from pale to white to yellow. The crash had decimated the top of his tibia and cut off blood flow to his foot. Doctors braced his leg to keep it together, grafted an artery from his right leg to his left. The surgery lasted more than five hours.

When Sara saw him afterward in the ICU on a ventilator and life support—six machines working to keep him alive—the gravitas hit her. “All of a sudden,” she says, “we went from a leg injury to a fight for his life.”

His blood hadn’t been clotting the way it should. He almost bled out. In the first 24 hours at St. Mary’s, they pumped him with 45 units of blood—more than four times his body’s capacity, because he kept leaking what they put in.

Three days passed. The tissue in his lower leg started dying, poisoning his kidneys. They wanted to shut down. The mangled limb slowly strangled the life out of him. He still couldn’t move his left foot. Couldn’t feel anything below his knee. Sara told him it wasn’t going to get any better. “I don’t want to carry around a junk limb,” Mike said. The doctors cut off his leg above the knee on December 16, 2008.

That’s when the serious pain hit. His nerve endings—frayed in the crash instead of cut cleanly—pulsed jolts of phantom pain. “The most excruciating pain,” he says. “It felt like a knife stabbing my calf. A vice grip breaking off my toes.” He finally stabilized, moved out of the ICU, and, after 13 days in the hospital, went home on Christmas Eve.

But where death backed down, grief marched in. Schultz had raced competitively since he was 13, when he discovered BMX bikes. Racing had been his life, mostly on dirt bikes and snowmobiles. He loved dirt bike racing best, but there were more opportunities in snowmobile racing, so he pursued it, turning pro at 19 and rising to the top ranks of the sport. Throughout, racing had intertwined his relationship with Sara, his high school sweetheart from Kimball, Minnesota. Had been their life. But just like that, it was gone. “We both started processing the loss of his leg but also the loss of our life as we knew it,” Sara says. “Racing was what he did, how we made our living.”

If fate had had its way with him, Schultz would be the guy a half dozen beers deep by noon embellishing what had been. Or bragging about what might have been. But even fate can take an unexpected turn when it meets a man as driven as Mike Schultz. He refused to feel sorry for himself. He didn’t ask, Why me? He knew why. He’d chosen his profession, he’d known the risks. Even if he’d bet against them. When the negative thoughts crept in, he focused on his goals. First, to get a prosthesis. Then learn to walk. That kept the depression at bay. “If you’re busy doing something,” he says, “you’re not worried about doing nothing.”

He had no idea that he’d keep stretching those goals until he would eventually refashion himself into an entirely new athlete, competing on an even larger stage with equipment he’d created himself—and, remarkably, outfitting his opponents with the same. That old Monster Mike? He was nothing compared to the Cyborg Mike to come.

On a sunny afternoon last fall, Schultz walked up the slope of his lawn from the horse barn to his house on the ten acres he and Sara own amidst the soybean farms of Stearns County, Minnesota, 70 miles northwest of Minneapolis and twenty minutes down the road from where he grew up. His intensity comes across in his direct, clear manner of speaking. You can hear it, too, in the way he tells his war stories—how he thrives on beating his competition into the ground. Glimpse it, even, in the mud-spattered dirt bikes in his garage. Yet all that fire is belied by gray Mark Ruffalo eyes, hinting at a kindness inside.

From the waist up, Schultz, who is 40, is the picture of an athlete: thickly muscled across the back and chest, with long, strong arms. His gait is relatively smooth, with only a slight hitch as he swings his artificial leg into place on each stride. It’s a $100,000 model made by Ottobock, the German prosthetics manufacturer, outfitted with a microprocessor that calibrates multiple tiny adjustments to accommodate each step. A technological wonder, really. But these prosthetics are delicate. They’re made for walking, not the kind of stuff Mike Schultz tackles. If he tried riding a dirt bike or a snowmobile on one of these contraptions, he’d shatter it.

Soon after Schultz learned to walk again, using his first prosthetic, he realized there were essentially two models for any activities more strenuous than walking: one leg for alpine skiing, the other for mountain biking. He tried the mountain bike version but sent it back. It didn’t have the range of motion or flexibility he needed to ride his snowmobile or dirt bike, let alone race. He figured he’d sell his bikes to help pay off his medical bills.

That is, until a new opportunity presented itself. One day in 2009, his brother-in-law told him that the ESPN Summer X Games in Los Angeles that July would include adaptive supercross, an event in which disabled dirt bike riders navigate bumps, jumps, and turns on a stadium course. That gave Schultz a fresh goal: to build his own specially modified prosthetic, one that could withstand the forcible contact. That was the moment he resolved to race again—and reinvent himself.

Schultz had no training in metal fabrication beyond high school shop class. But he’d built go-karts from lawnmower engines on the farm where he grew up; worked a job cutting, forming, and welding metal to build junkyard car crushers, then another to repair railroad cars; and maintained the suspension of his racing equipment. He spent five weeks designing a metal knee fitted with a compact mountain-bike shock absorber that would give him the same range of motion as a human knee, then another week in a friend’s shop learning to use a mill and lathe to machine the parts.

He tested his homemade knee’s durability and its capacity to absorb impact by jumping off a six-foot ladder a dozen times. It passed the test. His new Moto Knee, as he dubbed it, had a range of motion more than 50 percent greater than that of anything on the market. The moment of truth came when he took the bulky contraption, which had a carbon-fiber foot attached, for a ride on his dirt bike. Bolting it to the sleeve over his stump, he trembled with excitement. His new prosthesis allowed him to stand up on the pegs and shift his weight. Schultz smiles telling the story. “Right away, I knew this was going to work,” he says. “Game on.”

But it was a giant leap from his backyard to the supercross course in Los Angeles with its mammoth 90-foot jump. Although he had raced dirt bikes just a rung below the professional level, the Summer X Games proved a mighty challenge for him and his adaptations. He landed short on the jump and broke his carbon-fiber foot. The rest of the race, it kept slipping off the peg, but he managed to stay in the field and somehow finished second. After losing his leg, he had thought he’d never ride again. Now, here, only seven months later, he’d won a silver medal at the X Games. So began the journey of his transformation.

There was no question he’d keep racing. But when Schultz returned home, he set himself another goal: to design himself a foot that could help him win. He set up shop in his garage and, using a smaller mountain-bike shock-absorber than what he used for his knee, he came up with a new prototype—a device that could function like an ankle. He covered it with a foot-shaped metal shell and a rubber sole. As with his artificial knee, he was able to adjust the air compression in his new foot for resistance and flexibility. He tested the knee-foot combo at the 2010 Winter X Games, in Aspen, and won gold on his snowmobile in the adaptive snocross race, an event that traverses a series of bumps, jumps, and turns resembling a motocross track. His new Versa Foot, paired with his Moto Knee, gave him a complete leg that could be adjusted to meet the ever-changing conditions of courses and weather he faced on either his dirt bike or snowmobile.

He also now had two products that he could offer other amputees, from recreational athletes to elite racers. In July 2010, he founded the company BioDapt to design and manufacture his prosthetic knee and foot out of his garage shop. He had found a means to reclaim part of his life he’d lost—with replacements for the leg he’d lost—and saw an opportunity to do the same thing for others. Sure, it was a business venture, but there was something deeper driving him, the chance to help others reinvent themselves, even if that might one day hinder his own chances of success.

Schultz was signing autographs at the 2011 Winter X Games when a friend introduced him to an Iraq War veteran named Keith Deutsch. A serious snowboarder, Deutsch had been a machine gunner in the Army’s 244th Engineer Division. One night when he was out on patrol, his truck got hit by a rocket-propelled grenade, and he lost his right leg above the knee. Though he’d returned to snowboarding on a prosthesis built for downhill skiing, he wondered if there was something better on the market. He’d heard about Schultz’s models and asked whether they might work for snowboarding. Schultz said he’d find out. So he went to Powder Ridge, a ski hill near his home in Minnesota. It got ugly. “I was on the ground a lot,” he says. “I felt so handicapped. I hated it.” Three months later, he met Deutsch in Colorado to let him try the setup for himself. He liked it. “Dude,” Duetsch told him, “I haven’t snowboarded like this since I had two good legs.” Schultz also fared better himself on the board.

He soon returned to Colorado to demonstrate his wares at the Ski Spectacular, a winter sports festival for people with disabilities, many of them veterans. He found beauty in the mountains and inspiration among the veterans: If they can learn a new sport after all they’ve endured, he resolved, so can I. He sought out an experienced snowboarder who helped refine his technique, and with practice, he began to spend less time on the ground. In 2012, when the Winter X Games dropped snocross—his snowmobile discipline—and added adaptive snowboardcross, or boardercross, he signed up. It still wasn’t pretty, though: He finished fifth in a field of six.

Two years later, when he was back in Colorado fitting Evan Strong, a U.S. snowboard team member and below-the-knee amputee, at the national championship, Strong and a couple of others talked Schultz into competing in a time trial. In that moment, Schultz realized that his opponents, all below-the-knee amputees like Strong, had a serious advantage racing on human knees against him on his Moto Knee. “The real thing,” he says, “is extremely hard to beat.”

But this time, Schultz finished fifth out of ten. One of the coaches tried to recruit him for the 2018 Paralympics, still years away, but Schultz said no—if he couldn’t win, he didn’t see the point. He’d stick to racing his snowmobile and dirt bike, where he continued to rack up medals in adaptive events. He had also beaten all the able-bodied pros in the veterans class to capture the snocross national championship in 2012. “That’s pretty damn good for a one-legged dude,” he says.

In late October 2014, the U.S. Paralympic snowboard coach invited Schultz to compete with the national team in a World Cup event the following month. The kicker: The International Paralympic Committee had added a new class for athletes with a leg amputated above the knee or otherwise impaired: LL1, or lower limb impairment. That leveled the playing field.

Schultz had already conquered his goals in the non-Olympic sports of snowmobile and dirt bike racing, and now snowboarding offered a new one: representing his country on the international stage. He accepted the invitation, and in November he traveled to the Netherlands. It was there that he first encountered a 16-year-old Dutch snowboarder named Chris Vos, a prodigy who had, eight months previously, competed at the Sochi Paralympics. Vos wore an external brace on his right leg, which had been paralyzed in a childhood accident.

Remarkably, the neophyte Schultz bested Vos in their first duel, taking first and second in banked slalom—a solo timed run over bumps and around gates—and securing a spot on the U.S. national team. Then came another blow: In the boardercross at the 2015 Winter X Games, he came up short on a jump and shattered his heel and ankle. A surgeon screwed the 15 pieces back in place, but Schultz couldn’t walk for three months. He had to ease his way back onto his feet, first with a wheelchair, then a scooter, then crutches. At the following year’s Winter X Games, he returned to race his snowmobile, winning his fifth-straight gold in adaptive snocross, but the chronic pain in his good foot mired him in a dark mood. He was hurt so badly he wanted to quit snowboarding, but if he did, he’d lose the health insurance he had through the national team.

Schultz didn’t know then that the pain was caused by four bone spurs. Sixteen months after his injury, a surgeon discovered them while taking out the hardware from Schultz’s heel; fortunately, he was able to remove the spurs, too. Relieved, Schultz started racing his dirt bike again—only to crash on a training ride. He sailed over the handlebars, breaking six ribs, tearing cartilage in his thumb, and suffering a concussion.

Still not fully healed by the 2017 Winter X Games, he skipped the snowboard events, but won his sixth consecutive gold on his snowmobile, upping his X Games medal count to eight total in snocross and motocross. But the succession of injuries strained his marriage. After Mike and Sara had a daughter in 2013, Sara left her full-time nursing job to do public relations for BioDapt. As Mike’s injuries mounted, the stress of caring for a child and a wounded husband, on top of working, almost broke her. She wanted Mike to give up the dangers of dirt-bike and snowmobile racing and focus on snowboarding; he felt pressured to abandon the sports he loved. “Sara has grown exasperated,” Schultz writes in his new memoir, Driven to Ride. “She’s been picking up the extra workload with BioDapt while I’m injured, in chronic pain, and a bear to be around. I have a short fuse. Everything irritates me. Sara and I fight a lot.”

They finally hashed it out. Schultz agreed to dedicate himself to snowboarding at the 2018 Paralympics. Finally healthy again for the 2017 World Championships, at Big White, the ski resort in British Columbia, he finished second in banked slalom and fourth in boardercross, but the results discouraged him. Vos won both events, just as he had at the previous World Championships, in the Spanish Pyrenees. While Schultz had been injured it seemed like Vos had won almost everything.

Then they were racing on Gariwangsan mountain, outside Pyeongchang, in a reconnaissance event a year before the real thing. And fuck if Schultz didn’t wipe out again, clipping the back edge of his board in the belly of a roller and slamming his head into the ground to rack up another concussion. He had to sit out the boardercross event. Days later, he took bronze in the banked slalom. Once again, Vos won.

And then there he was, atop the slopes of Gariwangsan mountain, outside Pyeongchang, South Korea, for the biggest race of his life—the finals of the men’s boardercross at the 2018 Paralympics. Schultz was also wearing a target on his chest: He’d won the U.S. national championship in boardercross, then the world championship in both boardercross and banked slalom.

Yet through his business he’d become a beloved figure on the circuit, with 15 athletes using his models at the Paralympics. Noah Elliot, a skateboarder who’d taken up snowboarding after he lost his left leg above the knee to cancer at 17, had reached out to Schultz to get fitted with a prosthetic knee and foot. Schultz not only set him up with his products, he became Elliot’s first sponsor. “I ended up beating him on his own setup,” Elliot says of a banked slalom event. “Mike was the first one to tell me I’d won. We high-fived.”

In that manner, Schultz worked his way into the hearts of his teammates. They voted him the flag bearer to lead the U.S. delegation into the stadium in Pyeongchang for the Opening Ceremony. At competitions, he helped athletes tweak their Moto Knees and Versa Foots, fine tuning them to the conditions of each course. That took precious time from his own preparations, but he wanted the best for his clients—and wanted them at their best when he beat them.

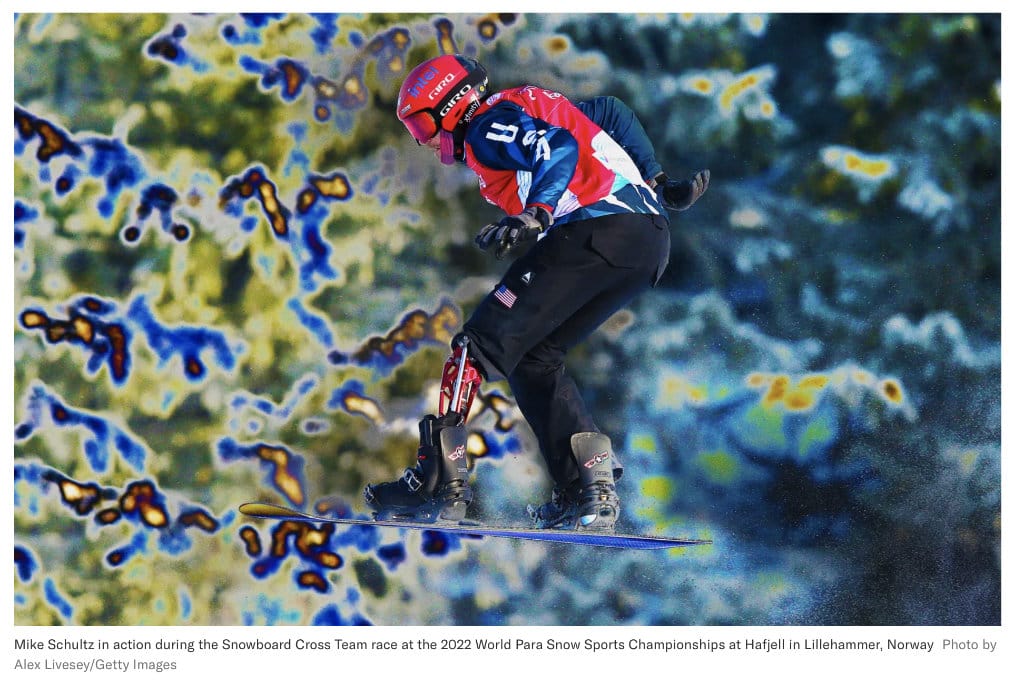

Now he edged forward in the starting ramp, gripped the metal frame, and cocked his board back. His left pant leg, trimmed below the American flag on his thigh, exposed his Moto Knee. Coiled opposite Schultz was Chris Vos, now 20 years old. Even though Schultz had dominated the past season, winning the World Cup, he knew that on any given day, Vos could beat him.

In the bleachers below the finish, Sara Schultz grew tense, pacing restlessly. For twenty years she’d been going to her husband’s races, ever since high school. This was the hardest part, standing by. She’d already watched Mike race four times that day, knowing that each run could be his last. At 36, his body had a lot of hard miles on it. With her eyes locked on the jumbotron, she threw a full-throated cheer up the mountain to her husband.

Out of the gate, Schultz nailed the quick start he wanted, legs bent, weight on his back foot, rolling into the first bump slightly ahead of Vos, picking up speed. Through the first two rollers, he continued to pull ahead of his rival. The third bump was bigger. Schultz got plenty of air, landing on the backside of the next roller. But Vos went too big, landing hard, and his brace failed to absorb the impact—he pitched forward.

Schultz heard Vos’s board skid out. At the next corner, he dared look back. Vos had gone down, but now he was up again. What a break. Focus, Schultz told himself. Don’t make a mistake. He cut his speed to 80 percent, but was still hurtling down the mountain, his board chattering along the ice-crusted snow. He looked cautious, palms down, trying to smooth out his ride. Three quarters of the way down, he snuck another look. No Vos. The 45-foot jump at the bottom still loomed. Just get it done and it’s all yours.

Down in the bleachers, Sara couldn’t contain herself. She was up on the seats, in her blue jacket with the white stars, clutching an American flag, jumping up and down, shouting, “Come on, Mike! Come on!” And then he was in sight, above the big jump. He shot up the six-foot ramp and went airborne, a silhouette in flight against the sky. His arms windmilled to keep his balance—rolling down the windows, they called it. Then he stuck the landing and hit the finish line.

He saw her first on the jumbotron, crying, shaking, screaming.

A decade of emotions were squeezed into that moment. The crash. The amputation. The fight for his life. The struggle to rebuild their life. Designing his knee and foot. Racing again. Learning to snowboard. Shattering his heel. Coming back. Battling Vos. Winning. Losing. And finally this. “Watching him cross the finish line wasn’t just him winning gold, but everything he’d been through and done,” Sara says. “All the sacrifices and hard work.”

“It was all of it,” Schultz says. “Snowboarding was just a small piece.”

After Pyeongchang, Schultz won the 2019 World Championship in banked slalom, then decided to retire, turning his focus to the business and his family. “I’d been strung pretty thin for a long time,” he says. Meanwhile, he continued to improve his products, bringing out a new prosthetic knee and foot for weightlifting and another prosthetic foot for downhill skiing. He’s also working on a miniature version of the Moto Knee for children. He recently built one for a 7-year-old boy in Minnesota who wanted to ride his dirt bike and another for a boy in Texas. There was nothing else available that would allow him to be active in the way he wanted.

The technical challenges provided a variation on athletic competition. “My second passion is problem solving,” Schultz says. That passion now prompted him to see if he could make a better brace for Chris Vos. A motorcycle mechanic had built the one Vos used in Pyeongchang, which didn’t always adapt well to bumpier courses—and caused Vos’s wipeout in the gold medal race.

Schultz’s call surprised Vos. “It was super unusual,” Vos says. “I was at first, ‘Does he really want to help me?’” Vos and his father traveled from their home in the Netherlands to Schultz’s shop in rural Minnesota, out between his house and the barn. Schultz found a new pivot point on Vos’s paralyzed leg for the external brace and supplemented the motorcycle mechanic’s spring with a mountain bike shock absorber. His new brace doubled Vos’s range of motion, and improved his ability to make adjustments and handle the impact of bumps. “For sure I’m a better racer with this setup,” Vos says.

The only problem was that retirement didn’t suit Schultz. He couldn’t keep away from competition and soon discovered a new passion: the Snow Bike, basically a dirt bike fitted with a single ski in the front, marrying his loves for snocross and motocross. At the 2018 and 2019 Winter X Games, he won gold in the new sport. Then he returned to the snowboard, with his sights set on the Paralympic Games in Beijing.

Behind his office and the smaller office Sara uses, past the shop where Schultz touches every part of every product he sells, is what he calls his “motivation room.” The size of a two-car garage, it’s stocked with an exercise ball, medicine balls, kettlebells, free weights, a bench press rack, a stationary bike, and an elliptical machine. It also houses memorabilia: framed photos of Schultz in action, nine dirt bike helmets, four shadow boxes filled with medals, the World Cup crystal globes, and—on either side of a large U.S. flag—his jersey from the 2018 Paralympic Games and the outfit he wore carrying the flag in the Opening Ceremony. But perhaps most motivating of all, above the door that opens into his shop, is a clock counting down the days, hours, minutes, and seconds to the opening of the 2022 Paralympic Games in Beijing, which began on Saturday.

This is where another gold could be won, with the work he does here. It’s where you can watch him, in a video on his Facebook page, hop up and down onto a knee-high wooden box, his prosthetic knee and foot cushioning his landing but not helping him leap, so he has to drag them up each time, pushing his good leg to the limits of fatigue. It’s a sight that makes his dedication to Beijing painfully clear.

He knows that another clock is ticking too, the one on his body. He’s 40. Has broken 12 bones. Lost a leg. Racked up a dozen concussions. This past summer, he crashed his dirt bike again—landed on his head, broke his sternum, and suffered two compound fractures in his back. He logged hours in the motivation room and on his mountain bike to regain his strength, mobility, and flexibility. These games are his last time on the sport’s biggest stage.

And they’re a great last challenge. In November, at the first World Cup event of the season, in the Netherlands, Schultz finished second to Vos in the two banked slalom races. The following month, in Austria, he again finished behind the young Dutchman. Finally, in January, in Sweden, Schultz beat Vos, this time in the boardercross. Though he’s competing in both banked slalom and boardercross in Beijing, his best chance for another gold is boardercross, in which he competes directly against his opponents, rather than simply racing the clock. “My mentality is better racing head to head,” he says. “It’s more aggressive, like motor sports. There’s more strategy.” (The boardercross final will be broadcast on Peacock on Monday, March 7th; the banked slalom final will be shown on Saturday, March 10th, also on Peacock.)

Vos will be there, racing on his new brace. So will an older, more seasoned Elliot. But Schultz has no regrets about helping rivals. “As an athlete, hell no, I don’t want to give them the same advantage,” he says. “But obviously it’s good for business, showcasing the best in the world are choosing our equipment for a reason.”

There is, of course, another reason he’s helping them. He knows the fragility of life, how quickly it can be altered. For better or worse. This final Paralympics is his chance to put himself and others right again. If only for that moment. “If one of my competitors breaks something at an event, I’m going to go to my toolbox and help them,” he says. “It’s just who I am.”