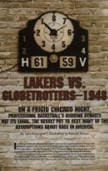

In February 1948, the Minneapolis Lakers ruled professional basketball. Playing their inaugural season in the National Basketball League prior to the formation of today’s NBA, the Lakers won the first of their five championships in six seasons and laid the cornerstone of their dynasty. But February 19, 1948, proved the Lakers day of reckoning.

On that date, the Lakers played an exhibition in Chicago against the Harlem Globetrotters. The Minneapolis Tribune billed the matchup the “Game of the Year.” The Minneapolis Star reported, “Chicago fans give Minneapolis such a chance to beat the fabulous Negro quint that they will likely fill the 20,000-seat Chicago Stadium.”

Both Minneapolis dailies identified the Globetrotters not simply as a basketball team, but as a Negro basketball team. Indeed, race not only defined the Harlem five, it would distinguish one of the most memorable games in basketball history, significant not only for its drama, but for the way the battle between the two best basketball teams in the world–one all-black, the other all-white– would alter the future of professional basketball.

In 1948, the United States remained a country divided by race. A year earlier, Jackie Robinson had cracked the color barrier in Major League Baseball, but he had not eradicated racial restrictions. Professional golf had a written policy that barred African Americans. The Basketball Association of America, a rival league to the NBL, had a tacit policy that similarly excluded blacks. Still a decade away from Rosa Parks’ courageous bus ride and the crusade for Civil Rights, the nation was ordered by Jim Crow laws and Ku Klux Klan intimidation.

The Globetrotters rode a 103-game winning streak, but bookies and fans alike figured the showmen had no chance against the mighty Lakers, who were eight-point favorites. On a Thursday night when a bitterly cold wind sliced through the Windy City, 17,823 fans–double the number ever to watch a pro basketball game in Chicago–filled Chicago Stadium. Thousands of fans in Minneapolis tuned into the radio broadcast of the game.

One of them was an eighth-grader at Fulton Junior High who listened in the upstairs bedroom of his Southwest Minneapolis bungalow. There were no black students at his school, none in his neighborhood. There were fewer than 5,000 blacks in the city. Like many Minnesotans of the day, young John Christgau had no personal experience against which he could evaluate the prevailing assumptions about African Americans.

When Christgau picked up newspapers for his route, he heard the cigar-chomping newspaper manager rant that Negroes were too muscular to shoot, too thick-headed to understand the complexities of basketball, too improvisational to play structured ball, too independent to be coachable and too large to jump. How was the boy to know any different? Until February 19, 1948.

The Lakers had one of the best players in the country in Jim Pollard, a 6’5” future NBA Hall-of-Famer nicknamed the “Kangaroo Kid.” But Pollard played in the shadow of the game’s most dominant player, George Mikan. The 6’10” Mikan, dubbed the “King of Basketball,” averaged 20 points per game by February, his 836 total points more than 200 ahead of the league’s next best scorer.

Seconds into the game, Mikan took a pass from Pollard, faked to his left, stepped around the Globetrotters’ Goose Tatum and deposited his famous hook shot for two points. Goose was a comic genius, the anchor of the Globetrotters’ routine, but he conceded seven inches and 50 pounds to Big George. With Tatum unable to stop Mikan, the Lakers grabbed an early 9-2 lead and threatened to run away with the game, true to expectations.

By the end of the first half, Mikan had scored 18 points, and the Lakers enjoyed a comfortable 32-23 lead.

The Globetrotters surprised them in the second half. They dashed up the court with the ball, intent upon wearing down the Lakers with their speed. On defense, they double-teamed Mikan aggressively. They opened the second half with a 10-2 run that narrowed the score to 34-32. The third quarter finished with the score knotted at 42.

The Globetrotters’ aggressive defense rattled the normally implacable Mikan, a religious man who had planned to be a priest before his basketball skills flourished. Frustrated, he knocked down Goose Tatum and was called for a technical. Later, Mikan hacked the ball from Tatum and was whistled for his fourth foul. Tatum made the free throw to give the Trotters a 55-54 lead late in the fourth quarter. Mikan answered with a basket to regain the lead, 56-55.

The Trotters managed to surge ahead 59-56, but Jim Pollard’s basket narrowed the lead to 59-58. The Trotters’ Ermer Robinson missed a long shot. Mikan rebounded and moved up the court. Tatum lurched for the ball, smacked Mikan instead and incurred his fifth foul. Out of the game, Tatum sank heavily onto the bench. Two minutes remained, but the Trotters seemed cooked along with Goose.

Mikan crossed himself at the free throw line. And missed the shot. Normally, the King of Basketball shot with 78 percent accuracy from the line, but this was the seventh of ten free throws he missed that night. The Trotters’ aggressive play had gotten under his skin.

Fouled again, Mikan made his next free throw to tie the game 59-59 with one minute remaining. The 17,823 fans at Chicago Stadium–two parts black and three parts white–screamed wildly in a deafening roar of Metrodome proportions. Marques Haynes brought the ball down the court. He dribbled down the clock at midcourt, waiting to set up a last-second shot. In his upstairs bedroom, John Christgau bit his nails.

With 20 seconds left, Haynes broke toward the left sideline, then cut toward the middle. Mikan and Pollard blocked his path. The Lakers’ Herm Schaefer managed to reach in and swat the ball out of bounds. The cheering ebbed momentarily. Ten seconds remained.

Haynes took the inbound pass and dribbled out toward midcourt. He spotted Ermer Robinson sprinting along the side. The two roommates had executed countless last-second plays. Haynes narrowed one eye slightly. Robinson understood. He stopped suddenly. Haynes bounced a pass to him, then set a screen against Pollard, who was guarding Robinson.

Robinson set and shot, a one-hander that was as much his trademark as Mikan’s hook, though not as reliable. He had missed two similar shots earlier that night. This one came from 30 feet out. As the ball floated toward the basket, the gun sounded. Time seemed to stop, the race question transcribed by the arc of the ball’s flight.

The ball swished smoothly through the net.

Fans spilled onto the court. John Kundla, the Lakers coach, shouted at the referee that the gun fired before Robinson’s shot. The Globetrotters carried Robinson into the locker room on their shoulders. The Lakers walked off stunned.

Young John Christgau went to sleep disappointed his team had lost, but he woke to a new world. The Globetrotters had not simply beaten the Lakers 61-59, they had elevated their people. The Negro quint had overthrown the master race and with it all of its subjugating stereotypes. “When Robinson’s shot was declared good, it was the end of the world for a lot of young kids like me and a lot of adults who harbored some pretty deep and perhaps unacknowledged racial sentiments,” says Christgau, who wrote a book about the game, “Tricksters in the Madhouse: Lakers vs. Globetrotters 1948.” “Maybe blacks were good basketball players afterall, despite the prevailing notions.”

Sixty years later, John Kundla, the Lakers coach, acknowledges the Globetrotters’ talent but blames the officials, hired by the Globetrotters, for not calling the game evenly. “I don’t want to complain, but that was the difference,” says Kundla, who lives in Northeast Minneapolis. “The Lakers were a much better team.”

Christgau, who has analyzed the game closer than anyone, disagrees. “No, the Lakers were not victims of bad officiating,” he says. “There may have been calls missed, but that went both ways. The Lakers lost because they underestimated how good the Globetrotters were.”

The Globetrotters could no longer be dismissed as mere showmen; they had proven themselves as proficient basketball players. A year later, they nullified charges their win was a fluke with a four-point victory in a rematch against the Lakers. Two years later, after the NBL had merged with the BAA to form the NBA, the owners voted to allow blacks to play in their league. In 1950, Earl Lloyd, Chuck Cooper and Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton became the first black players to sign with the NBA.

Today, the NBA bears the mark of the Globetrotters. Not only on its face–90 percent of the players are black–but in its style. The slow, plodding game the Lakers played in the 40s has given way to the stylistic dribbling, passing and above the rim play exhibited by the Trotters. That all began 60 years ago on a cold winter night in Chicago, when the Globetrotters proved their place on the court and paved the way for integration.

© John Rosengren