The young man sits alone in a hotel room, the last rays of sunlight leaking through the windows. Facing a single sheet of hotel stationery, he grips a fountain pen.

It’s the eve of the biggest game he’ll ever play. He thinks that because it’s his first real varsity game, and that there will be many more to follow – a full three seasons worth – but it’s bigger than that, we know now, because it’s also the game that will make him a legend.

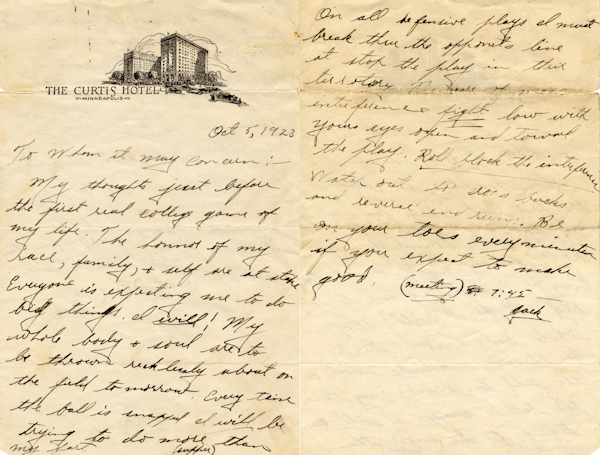

His thoughts are too big to hold inside. So much is swirling through him as the day shifts from late afternoon to early evening, the autumn night fast approaching, that he has to release them. So he writes in a burst of legible but hurried cursive: “To whom it may concern:”

* * *

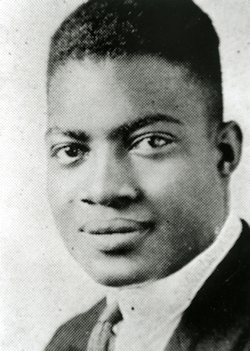

The young man is Jack Trice. Before Emmett Till, Johnny Bright and Medgar Evers, Jack Trice became a gridiron martyr. And was promptly forgotten.

Until many years later, when someone remembered. The river of his life, which had ebbed to a trickle gradually swelled over the course of 40 years until it overran its banks and flooded a college campus. This, then, is how that legend took shape.

* * *

October 5, 1923, John Trice, whom everyone but his mother calls “Jack,” sits alone in his room at the Curtis Hotel shortly before suppertime, when he will join his teammates from Iowa State, the other 26 young men who have made the 215-mile journey from Ames, Iowa to Minneapolis for tomorrow afternoon’s football game against the University of Minnesota. Jack may sense, but cannot know for certain, what hatred may take shape in the approaching shadows. He has conditioned himself to tread cautiously, even more so in new situations, so that he may gauge the environment, read the cues, and play his part. Trice is African-American, what the newspaper and many others then called “colored,” and that fact is central to his story.

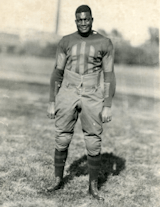

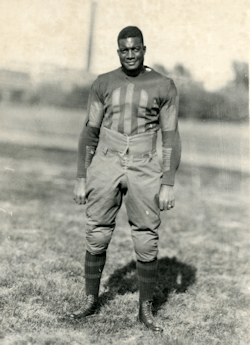

He stands 6’, 200 pounds, big for his day, bigger than most of his teammates, stronger than most of them, too. Yet the fact of his skin color emasculates him before lesser men, who can deny him a room, a meal at a restaurant, a place on the field. Who can strip him of his dignity just like that.

Trice is the only black player on the Iowa State football team, the first black varsity athlete at Iowa State College (as Iowa State University was then known) one of only a few black football players in the country at the time playing against white opponents. He will be the only black player on Northrop Field tomorrow.

Some schools simply refused to let African Americans in; others refused to let them play varsity sports. When Trice arrived, Iowa State only had about 20 black students, a tiny fraction of its student body of nearly 4,500. His teammates had welcomed him best they could without knowing, really, what it was like to be a marked man, forever suspect for his pigmentation. There were even schools in Iowa State’s own league, the Missouri Valley Conference, which refused to play against teams with a black player on the roster. That coming week, the University of Missouri athletic director would send a letter to Dean S. W. Beyer at Iowa State reminding the latter “it is impossible for a colored man to play or even appear on the field with any team” from Missouri, Kansas and Oklahoma. That was their gentleman’s agreement.

Minneapolis may be a Northern city, but that does not mean racism did not reside at that latitude. Just three years before Trice arrived, a white mob in Duluth, 175 miles north of Minneapolis, lynched three black men who had come to town with the traveling circus, accused of raping a white woman. The scene was familiar in Southern states but the first mob lynching in Minnesota.

The Great Migration of Southern, rural African Americans had not yet inflated Minneapolis’ black population the way it had other Northern industrial cities, but the Ku Klux Klan had nevertheless targeted Minnesota for expansion, swelling its ranks to 30,000 members statewide. Earlier in 1923, the Klan had smeared the Minneapolis mayor with accusations of drunkenness and lechery because he had the temerity to prevent police officers from joining the secret society and had investigated the Klan’s activities at the University of Minnesota. Though a jury convicted five Klan members, including its Exalted Cyclops Roy Miner, the Klan’s openly endorsed candidate in that summer’s mayoral election nearly succeeded in defeating the incumbent. His popularity was no doubt boosted by his platform to clear out the city’s primary vices of gambling and prostitution but may also have reflected fear and suspicion of the 4,000 African-Americans who accounted for one percent of the city’s population.

In the cross-burnings, parades and outdoor socials that proliferated around the state, the Klan saw itself as a political power as well as a social movement, intent on moral cleansing. The Klan had risen to such popularity and prominence on the University of Minnesota campus that it entered a float in that fall’s homecoming parade. Indeed, the very weekend that Trice and his Cyclone teammates came to town, 299 Klan members attended the first state convention across the river in St. Paul.

The vitality of the Ku Klux Klan in the Twin Cities did not render every white citizen a bigot, of course, but it did reflect sympathy among a segment of the population. Trice may very well have heard some of the stories of its activity and could only wonder if these influences might infiltrate Saturday’s game.

* * *

If you believe in destiny, you would say that the arc of Trice’s life had delivered him to this moment. He was born May 12, 1902, in Hiram, a small town in rural Ohio about 40 miles southeast of Cleveland, the only child of Anna and Green Trice. Both Anna’s parents and Green’s parents had been slaves. His father, who had fought American Indians as what the tribal people referred to as a “Buffalo soldier,” a member of the all-black 10th Cavalry Regiment of the U.S. Army, died when Jack was seven years old. His mother, who washed white people’s laundry, sent Jack to Cleveland at age 14 to live with his uncle’s family and attend East Technical High School. She wanted him to be “among people of his kind to meet the problems that a Negro boy would have to face.”

Trice, already big in high school, played football on several very good teams at East Tech under a very good coach, Sam Willaman, who had starred at Ohio State. Trice anchored the line, laying out opposing ball carriers with his signature flying tackle and blocking for the Behm brothers, Johnny and Norton, East Tech’s slippery running backs.

Their sophomore season, they lost only once. The next year, the defense did not allow a point through the first nine games. They didn’t lose until their eleventh game, the 1920 high school national championship game, played in Everett, Washington, after a three-day train ride, falling to Everett 16-7. In his senior year, Trice and his teammates did not lose. The big lineman with the gentle demeanor, one of only two African Americans on the team, was named All-State and left East Tech tagged in the high school yearbook as “undoubtedly the best tackle that ever played” at the school.

Success like that in high school football generally yields opportunities. Knute Rockne invited Johnny and Norton Behm to play for him at Notre Dame. Willaman landed the head coach job at Iowa State. But not so for black kids. Trice took a job on a road construction crew.

Then Willaman came calling later that summer. He talked the Behm brothers and two other Cleveland prep stars into playing for him at Iowa State. He also invited Trice.

In the years immediately following the Great War, college football enjoyed a Golden Age. (The National Football League was still in diapers, having started in 1920 under another name.) Trice had the chance to pursue a game he excelled at in this atmosphere of glory. He also cherished the opportunity to further his education.

Just one problem. Jack had tumbled into love. Leaving for the Iowa State campus in Ames meant leaving his girl, Cora Mae, behind. The solution? Marry her. In late July, the star-crossed lovers eloped temporarily, taking a train across the Michigan border, where they told the clerk Cora Mae was 19 years old (she was in fact 15) and that she came from Colorado. She returned with her secret to her parents’ home in Youngstown to finish high school, and Jack headed to Ames, satisfied. content.

* * *

If it wasn’t destiny that had delivered Trice to the Curtis Hotel on the eve of his first real college football game, then it was pure determination. Back then, schools did not offer athletic scholarships, and college had not been in the Trice family budget. Jack worked two custodial jobs, one in a downtown building, the other in State Gym to pay for tuition, books, meals and lodging–and to buy Cora Mae a special necklace. Jack’s mother helped out by mortgaging her house. Black students could not live on campus, so he found an upstairs room in the Masonic Temple building downtown, two miles from campus. The East Tech curriculum had not satisfied all of Iowa State’s prerequisites and he had to make up the extra work, but still averaged 90 percent in his grades.

Trice was determined – and idealistic. Enrolled in the animal husbandry program, he hoped to work with black farmers in the South, teaching them modern methods to cultivate their crops and support their families. He planned to put his education at their service in the spirit of Iowa State’s famous black alumnus, the scientist, botanist and inventor George Washington Carver.

Intercollegiate rules kept first-year students from playing varsity, so Trice worked out with the freshmen team, which played no games other than scrimmages against the varsity. Trice may have been big and strong but the high school standout still had a lot to learn. The line coach, George Hauser, who had been an All-American and now moonlighted for the Chicago Bears on Sundays, recognized the potential in Trice and schooled him in one on one workouts daily after practice. Soon the younger, smaller pupil had become the mentor’s equal, and Hauser predicted that Trice would one day become the best tackle in the country, better even than the black All-American from the University of Iowa, Duke Slater.

The freshman lineman made an impression on his future teammates, too. In a scrimmage against the varsity, he hit one upperclassman so forcefully, the older player, Harry Schmidt, recalled in an oral history that, “I’ve never been hit harder in my life.” One local newspaper reported on the young player’s dominance: “Jack Trice, the big colored boy from Cleveland, looked like a mountain in the line, being in every play, no matter whether it was a pass, plunge, end run, or punt.”

Aggressive on the field, Trice was submissive off it. He knew the place of the black man in white society, even north of the Mason Dixon line. He was friendly, but deferent, he spoke when spoken to and did not presume to enter his boss’s office without an invitation. He cleaned his fellow students’ muddy boots, sharpened their pencils, and assisted them into their bulky winter coats, always wearing a wide smile that pushed up his cheeks but did not expose his teeth . That endeared him to others.

Yet he remained unmistakably a black man in a white man’s world. As another student astutely later observed in the Iowa Agriculturist, “He sat next to us in the classrooms, strolled through the south side, attended convocation, worked out in the gym, rubbed elbows with us, but never stepped over the invisible barrier into our intimate confidences. It is only the truth to say that he lived alone and apart.”

Every day was a reminder of his otherness. Every night he was sequestered 700 miles from his young wife. Classes, practice, work. Repeat. Alone. Apart. But he did it day after day until summer washed up and he was able to return to the familiar, to Ohio, to his mother and Cora Mae.

And then, come autumn, he returned to Ames, only this time with his wife. She moved into his third floor room of the Masonic building downtown, enrolled in Iowa State’s Home Economics department, and soothed his isolation.

Jack wore his wedding ring everywhere, even on the football field. One night he snuck her into State Gym with the key he had from his custodial job. She was nervous they could get caught. He convinced her it was okay, and they skinny-dipped in the pool. He hadn’t known this kind of fun the year before.

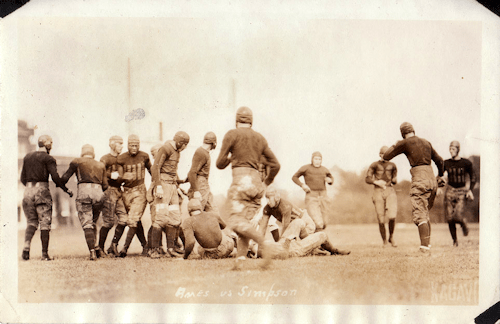

Cora Mae was there for the first game, a tune-up, against tiny Simpson College on the Cyclones’ home field. Trice did not start but once he got into the game, Cora Mae watched her No. 37 smother runners, block a kick, knock the ball loose, and recover a fumble. Ever stronger on defense, he struggled on offense to keep his man out of the Iowa State backfield and, in his frustration, got flagged for holding which cost his team a critical first down late in the game. But he added enough to help his team win 14-6, and impressed Sam Willaman sufficiently to be named a starter against Minnesota.

In the stands on that overcast day, Cora Mae no doubt felt pride watching her husband play so well. Perhaps she also flinched when the bodies collided, shocked at the force with which Jack and the others crashed into one another, protected – if that’s not too generous a word – by meek shoulder pads, thinly padded canvas pants and leather helmets (well before the face mask).

Indeed, college football was a dangerous game, often resulting in injury, sometimes in death. Not only was the equipment inadequate to the challenge of warding off blows, but defensive players used their hands and forearms as weapons to the head, neck and face – a practice not specifically outlawed until the ‘30s. The game churned up so much carnage – 18 deaths and 159 serious injuries nationwide in 1905 – that President Theodore Roosevelt insisted football be made safer or abolished. The college heads responded with the forward pass, which spread out the field of play, and modified the rules again after another 10 college football players were killed in 1909. Yet the game retained much of its raw brutality into the ‘20s.

So perhaps Trice sensed some malevolence looming when he stopped home to say goodbye to Cora Mae before catching the train to Minneapolis. In their upstairs room, he kissed her, wrapped his arms around her, and promised her his return. One of his coaches, waiting downstairs, reportedly yelled, “Come on, Jack. We have to go.” But Jack lingered, and held Cora Mae tightly. They looked into each other’s eyes. He didn’t want to leave her.

* * *

Minnesota was a good football team, not a powerhouse, but regularly one of the top squads in the Midwest. In the 20 times the Cyclones had played the Gophers, Iowa State had won only twice, the last time a quarter century before. The meeting in 1923 was the first after a seven-year hiatus. Trice and his teammates were decided underdogs, but they thought the Gophers were vulnerable. Injuries had sidelined four starters, including their captain and quarterback, Earl Martineau.

Trice felt the enthusiasm from the sendoff pep rally and the infectious optimism of his teammates last through the day’s light practice at Northrop Field and into the early evening, when he sat alone in his hotel room. He sensed the pressure of being a pioneer, poised to either confirm the notions against his race – They’re lazy. They don’t have the guts. They’ll quit on you. – or dispel them as so many lies.

He wished he could run onto the field that moment, put into action all of those thoughts stirring him, rise to pinnacle of his aspirations, but the game was still a night and half a day away. So he picked up his pen and wrote:

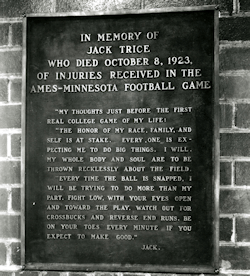

To whom it may concern:

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life: The honor of my race, family + self are at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body + soul are to be thrown recklessly about the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped, I will be trying to do more than my part.

That filled the first side of the sheet, and he wrote in parentheses at the bottom “(supper).” He then joined his teammates downstairs. Or perhaps he didn’t because the hotel staff would not allow a colored man to eat in the dining room – it might offend the other guests, hotel policy, you understand – so maybe he had to take his meal upstairs. Or they may have initially said he couldn’t eat in the dining room until his teammates protested and the staff relented, so Jack was able to dine with them. Accounts vary. Even though state law prohibited this sort of discrimination, it still occurred regularly in Minneapolis restaurants, hotels, YMCA and public beaches.

The spirit of prejudice Trice encountered in the hotel restaurant – at whatever level – could only rally his resolve to “do big things” for the honor of his race, family and self. During his supper, he no doubt pondered how, girding himself with reminders of his personal sessions with Coach Hauser, because when he picked up his pen again and wrote:

On all defensive plays, I must break through the opponents line at [sic] stop the play in their territory. Beware of mass interference, fight low with your eyes open and toward the play. Roll block the interference. Watch out for cross bucks and reverse end runs. Be on your toes every minute if you expect to make good.

He scribbled in parentheses “(meeting)” and “7:45” as though to explain why he stopped where he did, signed the letter simply “Jack,” and, at some point, folded the stationery and placed it in his coat pocket.

* * *

Saturday broke beautiful in Minneapolis, the sun sliding across Northrop Field, a slight chill to the autumn air, colored leaves beyond the bleachers – a perfect day for football with no portent of what was about to happen. When the gates opened at 1:00 p.m., an hour and a half before kickoff, the first of 11,000 fans, including 400 from Ames, began crowding the stands. The expectations on Trice continued to mount. Willaman exhorted his team to give their all. According to The Iowa State Student Daily, the coach told his team “I know of two men on this team who will fight.” He mentioned Trice first.

Back in Ames, Cora Mae took the streetcar into campus and headed to State Gym, where the Cyclone fans who had not traveled to Minneapolis paid a quarter to watch the game’s progress on a Grid-Graph, a kind of electronic scoreboard that reproduced the game on a gridiron signboard, relaying the progress of the ball, the play, and other information.

Minnesota kicks off. In the first series, Trice injures his left shoulder –probably breaking his collarbone – on a blocking play. The existing substitution rules stipulate that if he comes out, he will not be able to return to the game until the second half, so he shrugs off his teammates’ concerns and resumes his position at right tackle. He has come to do his part, the pain be damned.

On the next play, Iowa State fumbles deep in its territory and two plays later Minnesota scores and converts the extra point to take an early 7-0 lead. Iowa States comes back in the second quarter, relying on its strong passing game and runs by the Behm brothers to move the ball down the field. When the Iowa State fullback finally plunges a yard over the goal line, Cora Mae and the thousand or so other fans crowded into State Gym see the Grid-Graph light up, “Touchdown,” and cheer. The half ends with the score tied 7-7.

The game’s been played tighter than many expected. Trice has had several slipups on offense as he had the week before, allowing his man to tackle Iowa State runners for losses, but his defense has overshadowed his offensive shortcomings. On that side of the ball, despite his injury, he has factored into nearly every play, making tackles, filling holes ¬– breaking through the opponents’ line and stopping the play in their territory ¬¬– and generally inflicting chaos on the Gophers. He has been such a force that Minnesota has stopped running the ball to his side.

Willaman needs him to keep up the pressure. “How’s your shoulder?” he reportedly asks his star tackle.

It hurts. But Jack says, “I’m okay.”

Meanwhile, Trice and company have Minnesota coach Bill Spaulding worried. He asks his injured captain Earl Martineau to play. The quarterback’s throwing hand is bandaged, so he goes in at halfback.

After trading possession in the third quarter, Iowa State has the ball on its 20-yard line. The Gophers intercept a deflected pass and run it into the end zone. The Cyclone fans back in State Gym groan. Minnesota 14, Iowa State 7.

The Gophers kick off, and the Cyclones start driving. That’s when it happens, on a play when Norton Behm catches a pass. Trice goes down. Behm is tackled after a 10-yard gain. He pops up and returns to his position, along with all of the other players.

All but one. Jack Trice lies on the ground, never to play again.

According to a game summary printed that day in the Minnesota Daily, the University’s student newspaper, that is the play that killed him.

Elsewhere, accounts from players printed later that week indicate that Trice was injured playing defense, that he had “cut back to the right side of the line to check a Gopher line attack” and that on one such play, “he crashed into a fast-charging Gopher forward and fell flat on his back, wincing in pain.”

Decades after the fact, his own teammates and a coach recalled Trice throwing a roll block, a dangerous maneuver eventually banned, where the defensive player throws himself horizontally and rolls to trip up the runner. By this account, Trice ended the play on his back – rather than all fours, the way one does when the play is executed properly – and the onrushing Minnesota players trampled him.

The story is most often told this way, but just because it’s the most frequently repeated version does not validate its accuracy. Regardless of how the play actually happened, the result was the same, and questions linger. Did the Gopher players target Trice because he was the only black player on the field, intending to injure him, possibly even mortally? Or did they target him simply as a good player who threatened their chance at victory, perhaps wanting to knock him out of the game? Or, was the injury an accident, one that might even have resulted from Trice’s reckless play?

The result is the same. His insides crushed, Trice struggles to a sitting position. His teammates help him to his feet. He wants to stay in the game. If he comes out now, the rules do not allow him to return. He does not believe he has finished what he promised, ”to do more than my part.” He does not want to let hate – if it was hate – defeat him. But it is impossible. He can barely rise and stand, and can only walk off the field supported between two teammates as Gopher fans chant, “We’re sorry, Ames. We’re sorry.”

The Iowa State trainer insisted they take Trice to the University of Minnesota Medical Center. The physicians there did not fully grasp the seriousness of Trice’s condition. It’s uncertain they even diagnosed his broken collarbone. They had inevitably treated other black patients, but this time, perhaps persuaded by Trice downplaying the severity so he could return to Ames with his teammates, they did not provide adequate care. They released Trice only a few hours after he had been admitted.

Back in Ames, Cora Mae learned of the injury and probably experienced a brief panic familiar to anyone who has watched a loved one hurt in action. She bowed her head and prayed that he could be okay. The fact he walked off the field, she said later, relieved her of some worry.

Trice rode the train back to Ames in pain, settled on a straw mattress, and endured the final 12 miles to campus on a jolting bus ride, probably gritting his teeth or moaning, each bump making his insides feel like they were being trampled all over again. He was immediately admitted to the Iowa State campus hospital, where three local doctors, including Dr. James Edwards of the Iowa State faculty, looked after him. On Sunday, he seemed to be doing somewhat better. Cora Mae visited.

Around 4:00 p.m. that afternoon, Jack’s breath shallowed out and came in fits. His abdomen ached like he had been gutted. A fever raged through him. By nightfall, the attending physicians became alarmed. Someone wired Jack’s mother back in Ohio. Edwards summoned Dr. Oliver Fay, one of the country’s leading abdominal specialists, from Des Moines, 35 miles to the south. He arrived at 1:00 a.m. and confirmed that Trice was gravely ill. His intestines had been severely bruised and the tissue that covered his abdomen had become inflamed, a condition clinically known as peritonitis. It likely signaled an infection that could soon leak into his blood and spread to his vital organs, killing him.

An operation to locate the infection might have helped, but Dr. Fay feared an operation could prove just as deadly. Surgery during the early ‘20s remained a highly risky procedure with further infection a very real concern. He decided to wait and hoped that Trice’s athletic body could fight off the existing infection. Instead, his condition worsened.

Early Monday afternoon, one of Jack’s friends, a fellow black student, left his bedside to find Cora Mae. As she later recalled in a letter, she rushed from the cafeteria to his room. “Hello, darling,” she said.

He turned his gaze to her but could not speak.

And then his breath stopped.

Cora Mae heard the bells of the campanile, the campus bell tower, chime three times. It was three o’clock, Monday, October 8, 1923, and her husband was dead.

* * *

The school suspended classes the following afternoon for his memorial. His teammates carried him in a simple gray casket to the field fronting the campanile, the campus landmark, and draped his casket with a blanket in the school colors, cardinal and gold. Three, maybe four thousand students, faculty and football fans from the town, spread across the lawn. Jack’s mother, Anna, was there. She had arrived at 6:45 p.m. the previous day, too late to say goodbye.

Anna and Cora Mae and the others assembled listened to a faculty member sing a solo of “Abide with Me,” then to the college chaplain deliver the invocation. The captain of the football team declared, “He fought harder than the rest of us; he gave his life for Ames,” and then they heard Coach Willaman say, “He was a man of fine standards, a good student and one of the best athletes I have known.” President Raymond Pearson added, “Jack Trice was an honor to his race, to Iowa State College and a conspicuous honor to those activities which he participated in. His characteristic manhood and his sportsmanship we admired.” Jack’s mother and his wife no doubt found solace in the kind words and in the money collected from the Iowa State community–“to express in a material way the sympathy of the college”– $2,259, that covered funeral expenses, paid off Anna’s mortgage and provided both Anna and Cora Mae with a little nest egg. Yet after they had returned to Ohio and buried Jack alongside his father in the Hiram cemetery, Anna confided in a letter, “While I am proud of his honors, he was all I had and I am old and alone, the future is dreary and lonesome.”

The climatic moment of the memorial service occurred when President Pearson read aloud the letter that Jack had written the night before the game. After his death, it had been found in his coat pocket. “The honor of my race, family and self are at stake. . . . I will be trying to do more than my part. . . . Be on your toes every minute if you expect to make good.”

As Pearson spoke Jack’s words and those spread across the lawn absorbed them, the legend of Jack Trice began to take shape. In the wake of the Great War, his death was viewed through the lens of one who has fought for glory at the highest level and paid the ultimate price. The Ames Daily Tribune referred to him as a “fallen warrior.” The Minnesota Daily ran an elegy that began: “Tribute to him, who, in the first fair flush/Of Glory, won upon a fatal field/Fell, hurt, before the fierce contested rush/And joy of worthy battle; fell to yield–“ The Minnesota Alumni Weekly anointed him “a hero with all the blaze of glory and spectacular accomplishment which is due heroic martyrdom.”

* * *

For all the praise, the question remained: Was Jack Trice murdered?

The Associated Press reported that Trice “died from injuries received when most of the Minnesota line piled on top of him.” John Griffith, the athletic commissioner of the Intercollegiate Conference, telegrammed Iowa State Dean S. W. Beyer to inquire whether he thought Trice’s injuries resulted from “unfair play.” Beyer replied, “Willaman and the men under him advise me that they did not discern any special massing on Jack Trice.”

Griffith answered, “Inasmuch as Mr. Trice was a colored man, it is easy for people to assume that his opponents must have deliberately attempted to injure him. In my experience where colored boys have participated in athletic contests, I have seen very little to indicate that their white opponents had any disposition to foul them.” Thus concluded the inquiry.

Lotus Coffman, president of the University of Minnesota, sent a letter to his counterpart at Iowa State, President Pearson, ten days after Trice’s death with his condolences and his observation that the play had occurred “directly in front of me” and “it seemed to me that he [Trice] threw himself in front of the play on the opposite side of the line. There was no piling up.” This may very well be an accurate summary, but it is also easy to discern Coffman’s interest in interpreting the play as he did.

Griffith and Coffman, even Breyer and Pearson, had motive to whitewash any racial profiling by the University of Minnesota players; they all stood something to lose if Trice’s death turned out to be a hate crime. Yet there was no talk of conspiracy or cover-up in the stories of Trice’s injury and death that ran in the African-American press. Nor did his family hint at this. Cora Mae’s father even wrote Pearson to clarify that his daughter had no intention of filing a damage suit as was rumored several months later.

On the 50th anniversary of Trice’s injury, Harry Schmidt, one of the teammates who helped Trice off the field, later said in an oral history that he saw Trice throw the block and get stepped on but that it was not done intentionally. Johnny Behm, Trice’s teammate and friend as far back as high school, was quoted by Newsweek in 1983 as saying he did not think the attack on Trice was racially-motivated but that it was intentional: “The Minnesota boys just did what anybody does when a man is real good and making you look real bad.” Merl Ross, who had been the Iowa State athletic department business manager at the time of the incident, said in 1989, when he was 91 years old, that Minnesota players wanted Trice out of the game because he was black. “I feel sure that was their purpose, to get him out of the game,” Ross told a reporter from the Ames Tribune. “They wanted to get him out of there. And that’s what they did.”

In view of all of the conflicting accounts, suspect motives and strained memories, it is difficult to know what actually happened and why. We are left with the simple facts: Jack Trice suffered serious injuries on the field. Two days later, they killed him.

* * *

The Cyclones wore black armbands the rest of the 1923 football season, and Coach Willaman posthumously awarded Trice a varsity letter, which he mailed to Jack’s mother. Talk on campus sought to find a way to honor Trice’s memory in a more permanent way. By the end of the year, the Varsity Club had hung a bronze plaque in State Gym embossed with the words from the Curtis Hotel letter. Cora Mae returned from her parents’ house in Youngstown, Ohio, to campus for the official dedication in February.

But then, outside of Cora Mae’s heart, Jack’s memory dissipated, lost upon the following generations of Iowa State students.

Until 1973, when that plaque in the State Gym, by now obscured by bird droppings and dust, caught the eye of an athletic department tutor who told an English professor, Charles Sohn, about it. Sohn had his students research Trice, and they came across details that included an article written 16 years earlier for a campus publication by an undergraduate named Tom Emmerson after he had heard Trice’s story from Harry Schmidt. One of Sohn’s students suggested the new Iowa State football stadium under construction should be named after Trice. And a cause was born.

The national crusade for civil rights, a struggle still incomplete; the rise of student activism, spurred by the Vietnam war; and a couple of violent racial incidents in Ames ripened the atmosphere for the students of Iowa State to champion Trice, who had given his life for the school. They formed the Jack Trice Memorial Stadium Committee and shortly afterward the student government voted unanimously to support the idea of naming the new stadium after Trice. The student newspaper also backed the idea. That spring, 1974, they collected 4,000 signatures on a petition to honor Trice’s heroism in the stadium’s name.

The idea met resistance from the administration and donors that would hold steadfast for two decades. The establishment, comprised of white, aging men who had accumulated status and power, did not want to be dictated to by college kids. These men had come of age during an era of unquestioned prejudice that imbued them with bias, implicit if not explicit. So when the 50,000-seat, $7.6 million stadium was completed in 1975, the Board of Regents filibustered, voting to delay naming the stadium until its debts were paid off. The Trice constituency viewed this as a way for the administration to wait for a donor to step forward to purchase eponymous rights. Sohn bemoaned the decision made by a group of “narrow-minded, fat cats.”

The delay tactic was also likely posited on the assumption that once the group of students agitating for Jack Trice Stadium graduated, the movement would fade. But Sohn, who became the faculty advisor to the student government, and Emmerson, by then faculty advisor to the student newspaper, determined not to let that happen. They continued to trumpet Trice’s story to a receptive audience – once each new wave of students heard the story of a young black man playing for his race, killed in action, they were hooked, ready to sign a petition, wear a “We’ll Carry the Torch of Jack Trice” button, hawk Jack Trice T-shirts, write guest editorials in the city newspapers and even design commemorative stationery.

While the naming of the stadium hung in limbo, the Jack Trice Stadium movement accelerated. A popular columnist for the Des Moines Register, Donald Kaul, began criticizing the University administration for its position, which broadened support behind the Trice name. The student government raised money to run radio advertisements. Several Iowa State students paid for a billboard that proclaimed, “Welcome to Ames, Home of Jack Trice Memorial Stadium.” Others paid for an airplane to fly a “Welcome to Trice Stadium” banner over the unnamed stadium during a game.

Iowa governor Robert Ray proclaimed, “It would be a fitting memorial to Jack Trice” to name the stadium after him. Other high-profile figures such as Senator Hubert H. Humphrey; the actors Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward and Ed Asner poet Nikki Giovani and Olympian Rafer Johnson raised their voices in support. Along the way, the Trice narrative shifted to fit the movement’s purposes, casting him as a racial martyr. The embellishment held, as articulated by another Register columnist, Chuck Offenburger, that Trice was “a great black player of another era–an era when blacks were often beaten to death, as Trice essentially was, because of his skin color.”

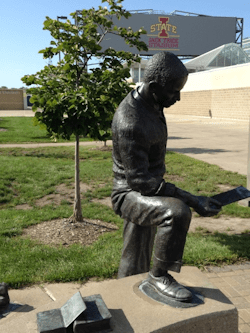

By 1983, the stadium debt had been paid off without a singular donor making a contribution large enough to justify making the stadium his or her namesake, so ISU president Robert Parks proposed – and the Board of Regents rubber-stamped – the compromise “Cyclone Stadium/Jack Trice Field.” That disillusioned those who had campaigned for Trice Stadium, in large part because Parks’ longhand was regularly shortened to “Cyclone Stadium.” So the movement persisted, still lobbying for full recognition at the stadium but also raising funds for a statue of Trice to be placed on campus. That effort, largely led by Sohn, achieved its fulfillment on May 7, 1988, when a $22,000, 6’5 bronze statue of Trice depicted as a student reading his famous letter was dedicated on campus in a ceremony attended by several of his relatives.

Almost ten years later, a new university president, Martin Jischke, recommended that the Board of Regents rename the ISU football stadium. On August 30, 1997, President Jischke formally dedicated “Jack Trice Stadium.” Referring to Trice as a “role model” and “inspiration” who symbolized the ideals of “devotion to the team, giving one’s all,” Jischke declared, “He has become a hero—not so much for what he accomplished, because his life was cut short—but for what he represented.” And with that, Iowa State not only ended a long debate, it became the first Division-I school in the country to name a stadium after an African-American athlete – and remains the only one.

* * *

The Trice myth has since flourished at Iowa State. A life-size bas relief is set into the brick wall of State Gym. Photographs of Trice and his teammates ring the gym floor. His letter is displayed in a glass etching along with a life-size photograph in the Jacobson Athletic Building. Another rendering of the letter greets all who enter Bergstrom Football Complex, scrolled on a video and read aloud alongside more larger than life photos of Trice. Outside Jack Trice Stadium, his statue greets all who enter. Along the concourse inside, another life-size bronze bas relief and four brass panels recount his virtues. The tunnel that the players pass through from the locker room to the field bears a large color mural of Iowa’s immortalized hero along with the text of the letter. He has become the face, the name and indeed, the very spirit of Iowa State.

Although Trice remains anonymous outside of Iowa, he has risen to a level of prominence in Ames of mythical proportions, a Paul Bunyan of gridiron lore. When you strip away the embellishments and reckon that he did not win a Heisman, did not captain a national championship – hell, he played only one real college game and didn’t even finish that – there’s still something there to admire that won’t go away.

Consider once again that young man alone in his hotel room. Night has fallen. He has finished his letter. He folds it, stuffs it in his coat pocket, and heads off to the team meeting – eyes open, ready to do big things.

© John Rosengren