It’s hard to say where the Baseball Reliquary began. Maybe it started with a drop of Juan Marichal’s sweat or Bill Veeck’s autobiography. It might also have been a pubic hair purportedly belonging to St. Nick. Pinpointing its beginnings is as difficult as defining the Reliquary itself.

It’s been called “the fans’ Hall of Fame,” “the antithesis of Cooperstown,” and “the motherlode vein leading to the heart and soul of baseball.” It calls itself “a nonprofit, educational organization dedicated to fostering an appreciation of American art and culture through the context of baseball history,” but that doesn’t really capture the Reliquary’s unique nature. “It’s hard to categorize,” admits Terry Cannon, 62, a part-time library assistant in Pasadena, California, who founded the Reliquary in 1996. “It’s an amazing living organism in all of the directions it has moved into, but it retains the vision I started with.”

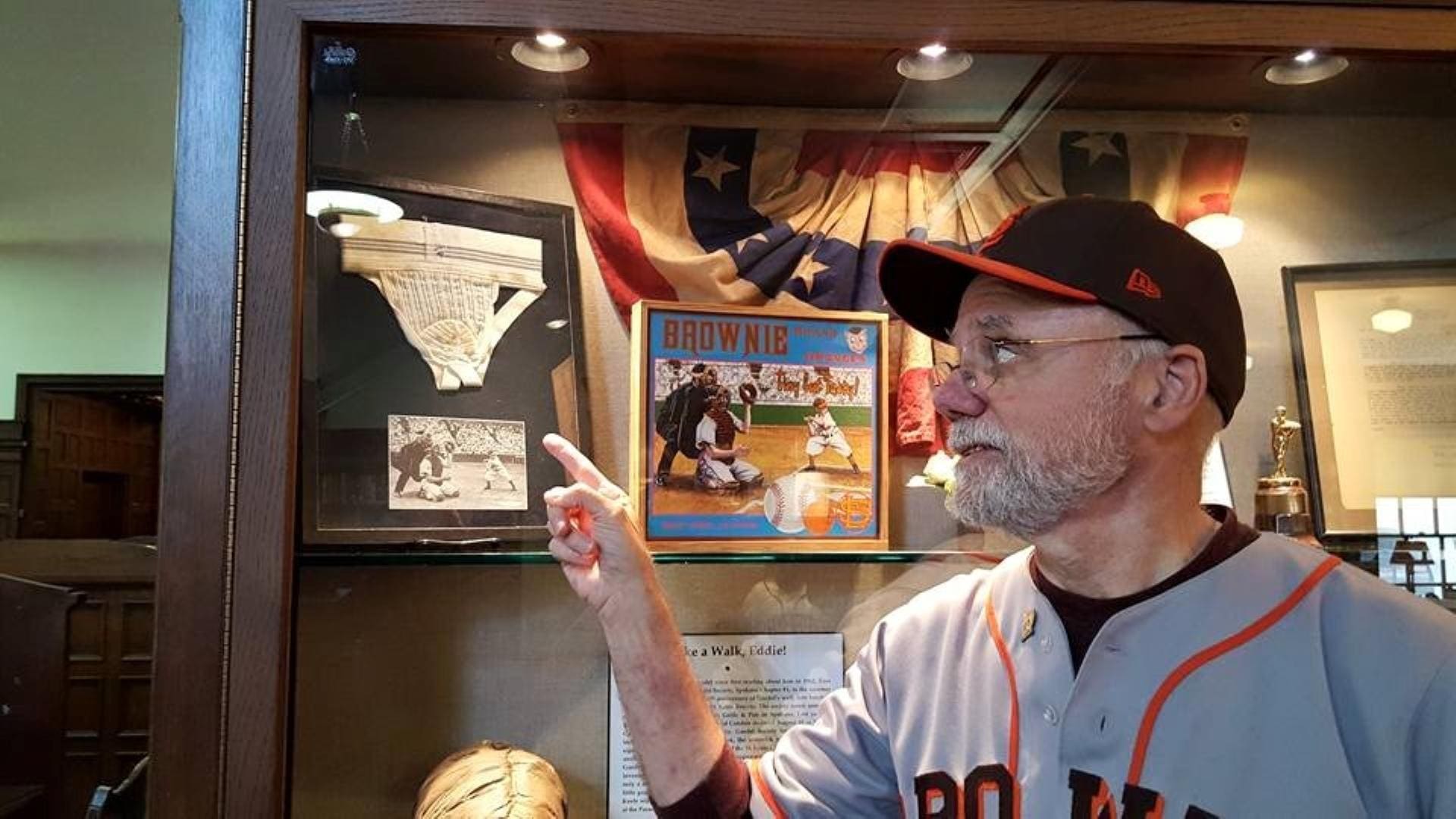

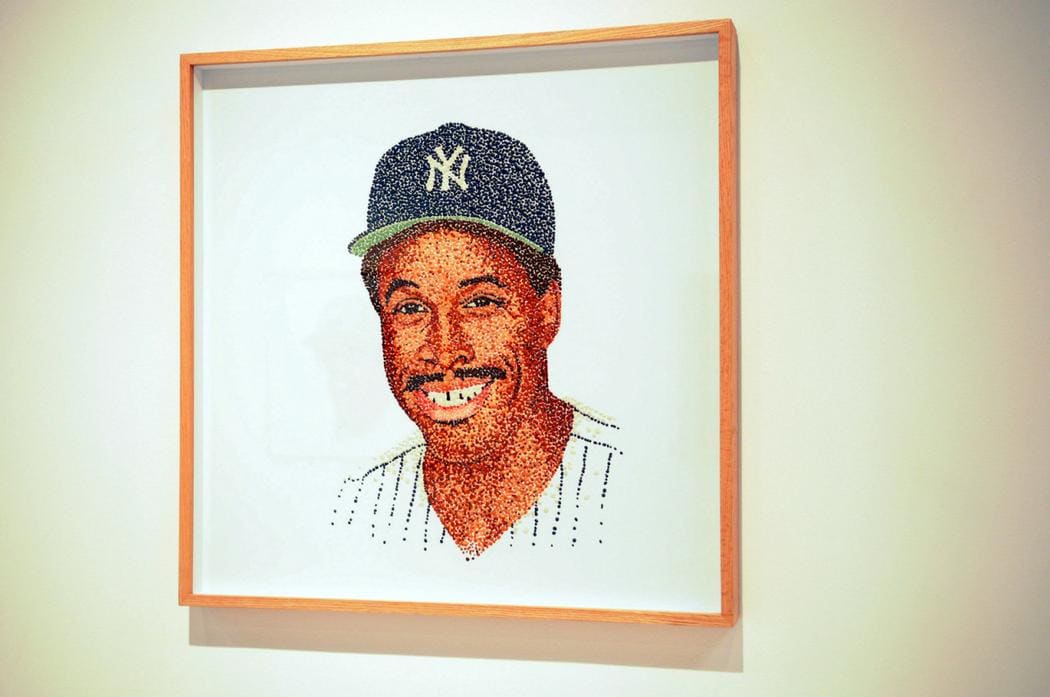

Cannon’s vision, to create an organization that embraced his dual passions for art and baseball, has evolved over the past two decades into a nomadic Hall of Fame that celebrates all that is wacky and wonderful about the national pastime. It stages four to six annual exhibits, mostly in Southern California libraries, from its collection of artifacts, ranging from Eddie Gaedel’s jock strap to a portrait of Dave Winfield constructed with chewed bubble gum. The Reliquary counts 51 honorees in its Shrine of the Eternals, including expected mavericks like Bill Lee, Marvin Miller, Pete Rose, Jim Bouton and the San Diego Chicken as well as lesser-knowns such as Steve Dalkowski (the hardest throwing pitcher never to play in the major leagues) and Lester Rodney (the journalist who advocated for integration of organized baseball but was ostracized as a communist).

Exactly what you might expect from a man who was enamored of Bill Veeck’s autobiography Veeck as in Wreck in 1963 when he read it as a ten-year-old. Veeck had Cannon from the first chapter, with his description of hiring the three-foot, seven-inch little person Eddie Gaedel to pinch hit. “Eddie Gaedel was an assault on the baseball establishment,” says Cannon, a self-confessed nonconformist. “I love that. Veeck’s vision in terms of being a gadfly is a little of what I was looking to do with the Reliquary.”

Cannon caught a whiff of the impression a good artifact could make three years later, when, at the first exhibition game the California Angels played at their new Anaheim Stadium, he spotted Giants pitcher Juan Marichal running sprints in the outfield and asked for an autograph. As Marichal signed Cannon’s game program, a bead of sweat dripped from his forehead onto the page. Cannon marveled at how it dried the next day into a brown blotch. “I went around the neighborhood showing other kids—’This is Juan Marichal’s sweat’,” Cannon says. “That could have been the beginning of the Reliquary, of gathering artifacts that tell stories.”

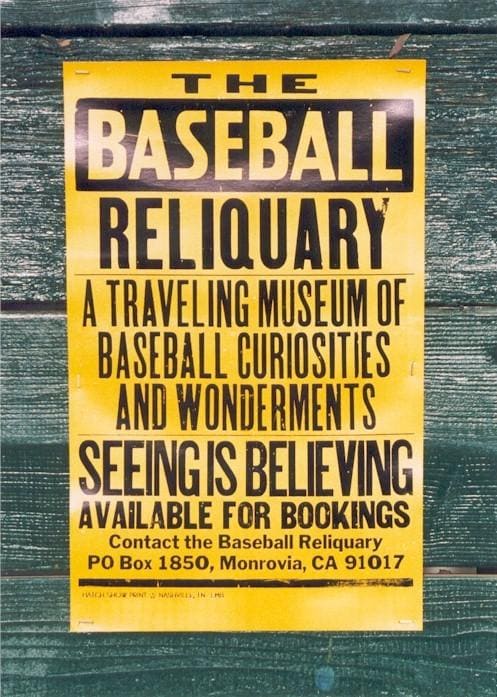

A poster for the Reliquary. — Courtesy Terry Cannon

Or at least it planted the seed, nurtured in later years by the Mardi Gras parties Cannon attended with his wife Mary. They dressed in costume, he as the Pope wearing a Mitre decorated with baseball insignias on it; they carried bogus Vatican artifacts displayed in elegant boxes, such as the hair once adorning the holy pubis of St. Nicholas. “We had a lot of fun with that,” he says. “When I was starting the Baseball Reliquary and looking for a name, the way we planned to exhibit early items like a hot dog partially eaten by Babe Ruth didn’t seem much of a stretch from what you would find of saints in the basements of Italian churches.”

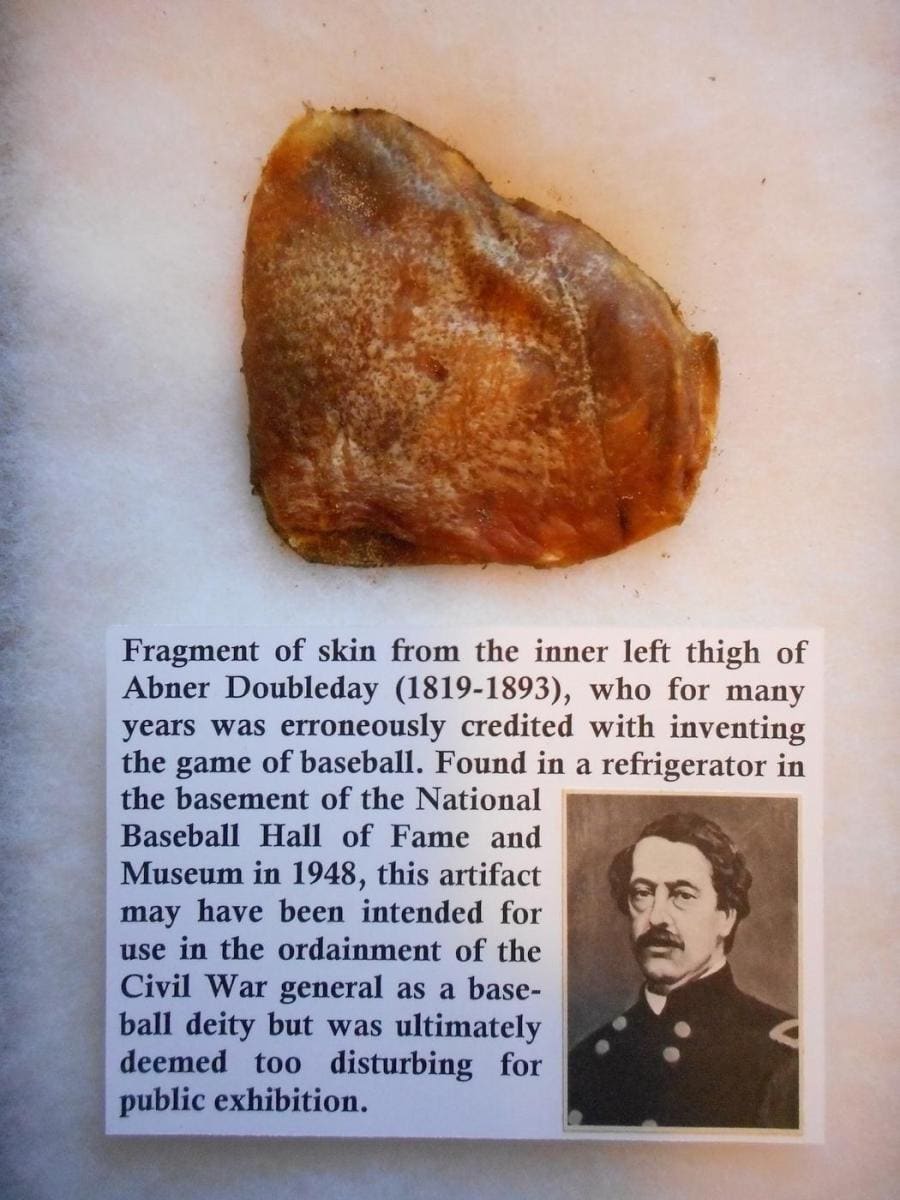

Cannon, an agnostic, did not grow up Catholic, but his wife did, and there are strong strains of Catholicism that run throughout the Reliquary, from its name to its memorabilia. Consider the tortilla imprinted with an image of Walter O’Malley’s face (remind you of Veronica’s cloth or a certain grilled cheese that made headlines not long ago?); a piece of skin supposedly taken from Abner Doubleday’s thigh (similar to grafts and bone fragments populating those Italian church basements); and the panties that Wade Boggs insisted his mistress wear during his hitting streak (granted, no parallel there in Catholic tradition). The organization does not go in for piety; rather, the Reliquary revels in irreverence, very much in the spirit of Veeck, its “spiritual guru.”

The Dave Winfield bubblegum portrait by Pat Riot. — Courtesy Terry Cannon

The Reliquary website proclaims that it “gladly accepts the donation of artworks and objects of historic content, provided their authenticity is well documented.” Cannon admits this is more a jab at the memorabilia craze, which he finds “laughable,” “ridiculous,” and “obscene,” with values of legitimate objects of interest artificially propped up by auction houses. “Our objects offer a counterpoint to that,” he says. “We don’t really care about their ‘authenticity,’ because we’re more interested in an object’s ability to convey a story.”

He points to the Walter O’Malley tortilla for the way it conveys the story of Chavez Ravine. The city of Los Angeles evicted poor residents, many of them Mexican-American, in order to build Dodger Statdium; it’s one of the most egregious uses of eminent domain on record, but history has wrongly assigned O’Malley the blame. In fact, Cannon explains, when O’Malley found out what had happened on the site where he wanted to build Dodger Stadium, he offered the few remaining residents compensation that exceeded the actual value of their property for them to relocate. “This item resonates because it’s unique and is a powerful way to tell the story,” Cannon says.

Additional relics in the collection include baseballs autographed by Mother Teresa, a rubber model of Mordecai Brown’s missing finger, Dock Ellis’s hair curlers, a Charlie Finley orange baseball and one of Cannon’s favorites, a hunk of dirt from Elysian Fields, site of the first recorded game of organized baseball, played in 1846. He received it from the great-great-great grandson of James Orr. Orr, a poet, supposedly dug up the soil surreptitiously after being moved by watching a game played there and predicting baseball would become a grand and noble sport. “That’s an important artifact,” Cannon says. “It was dug up and conserved by a man of incredible vision. It ties in the idea of baseball and poetry, baseball and art. We’re always seeking that out.”

Actual soil from the actual Elysian Fields. — Courtesy Terry Cannon

He’s serious when he says that. Indeed the Reliquary has a scholarly bent, making its expansive archives available to the public through the Institute for Baseball Studies hosted by Whittier College in Southern California and the Latino Baseball History Project, a collaboration with California State University, San Bernardino, that documents baseball’s social and cultural significance in the Latino community.

Three years after founding the Reliquary, Cannon added the Shrine of the Eternals in 1999. Where members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America select inductees into the National Baseball Hall of Fame primarily on the basis of statistics, the Reliquary general membership votes on Eternals who animated the game and entertained fans with their colorful personalities. There’s very little overlap in the two pantheons’ membership; Yogi Berra, Dizzy Dean, Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, and Casey Stengel are the only people enshrined in both. Veeck, Ellis, and Curt Flood made up the first class of Eternals.

For many of those selected, it is the first time they have recognized in a positive way for their contribution to baseball. As a result, the induction ceremony can become an emotional experience. Ellis, who infamously pitched a no-hitter while tripping on acid and anonymously spent much of his retirement doing social work, broke down while accepting his award. “I realized right then and there that we were going to be successful,” Cannon says. “Because we were honoring people who hadn’t been honored elsewhere.”

Abner Doubleday’s skin fragment. — Courtesy Terry Cannon

This year marked the 17th annual Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day. On Sunday, July 19, Cannon kicked off over two hours of festivities by raising an oversize cowbell and, just as Hilda Chester used to do at Ebbets Field, clanging it over his head. Audience members joined with their collection of bells to rattle the halls of the Pasadena Central Library for nearly a half minute. After some introductory remarks, Cannon asked the 200 or so people present to rise for the traditional—at least in the Reliquary sense—singing of the national anthem and introduced Jackie Lee. An 82-year-old woman dressed in a skimpy gold lamé leotard walked onto the stage, where she stood on her head, splaying her long white hair across the hardwood floor, and started to sing in a quavering soprano, “Oh, say can you see…”

With moments alternately humorous, serious, and poignant, the ceremony was devoted to stories, mostly obscure, about this year’s award recipients. As a warmup, Cannon presented the Hilda Award to Tom Keefe, founder of the Eddie Gaedel Society, and the Tony Salin Memorial Award to Gary Joseph Cieradkowski for his “commitment to the preservation of baseball history” in creating the Infinite Baseball Card Set blog.

The meat and potatoes of the event came with the presentations and acceptances of this year’s three inductees into the Shrine of the Eternals: Sy Berger, the “Father of the Modern Baseball Card” who designed Topps’ 1952 line of cards; Glenn Burke, MLB’s first gay pioneer, closeted to the public but open with his teammates during four years with the Dodgers and A’s; and Steve Bilko, a slugging star and strikeout king (as a batter) for the Los Angeles Angels during the denouement of the Pacific Coast League.

Berger’s son Glen gave an entertaining introductory speech spiked with name-dropping anecdotes about his father with Willie Mays, George Steinbrenner, and Brian Epstein (yes, that one, the Beatles’ manager). A five-minute video clip introduced Glenn Burke. Folk singer Ross Altman sang a tribute to Bilko with his harmonica and acoustic guitar: “When that bat connected, it was music to our ears/Just like the Babe before him, he put them in the stratosphere.”

Ross Altman, the musical guest at the 2015 Shrine of the Eternals Induction Day. Photo by Jesse Saucedo

Membership in the Reliquary is open to anyone willing to pay $25 in annual dues. There are nearly 300 such people, and their money, along with a small annual grant from the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, composes the budget, which doesn’t always cover travel expenses for inductees and speaker stipends. Since all Reliquary events are free, the primary perk of membership is being able to vote in the annual election of inductees into the Shrine of the Eternals.

There are other, less tangible benefits of membership. Jon Leonoudakis, a producer who had made TV commercials for clients such as Honda and interactive displays for theme parks like Disneyland, attended his first Reliquary induction ceremony in 2002. Leonoudakis had been a baseball fan since he was five years old, but had become disillusioned by steroid use and corporatization of the game. Watching the Reliquary induct Mark Fidrych, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and Minnie Miñoso into its Shrine, he says, reignited his love of the game. “The vibe and the crowd–there was a guy dressed in full 1919 regalia–launched me into the stratosphere of fandom,” he says. “It totally changed the journey of my life.”

Leonoudakis resolved to make documentaries that told the story of the game and started, naturally, with one about the Reliquary, titled, Not Exactly Cooperstown, released in 2014. He’s currently finishing a film about Arnold Hano, the prolific baseball writer and 2010 recipient of the Reliquary’s Hilda Award, given to recognize distinguished service to the game by a baseball fan. Other recipients of what Cannon calls “the baseball fans’ equivalent of the Oscar or Emmy” include Bill Murray and Sister Mary Assumpta Zabas, who has baked cookies for the Cleveland Indians’ players since 1984. “The Reliquary is the only Hall of Fame where the fans get to vote,” Leonoudakis says. “They embrace the fans’ importance and recognize fandom is the lifeblood of the game.”

© John Rosengren