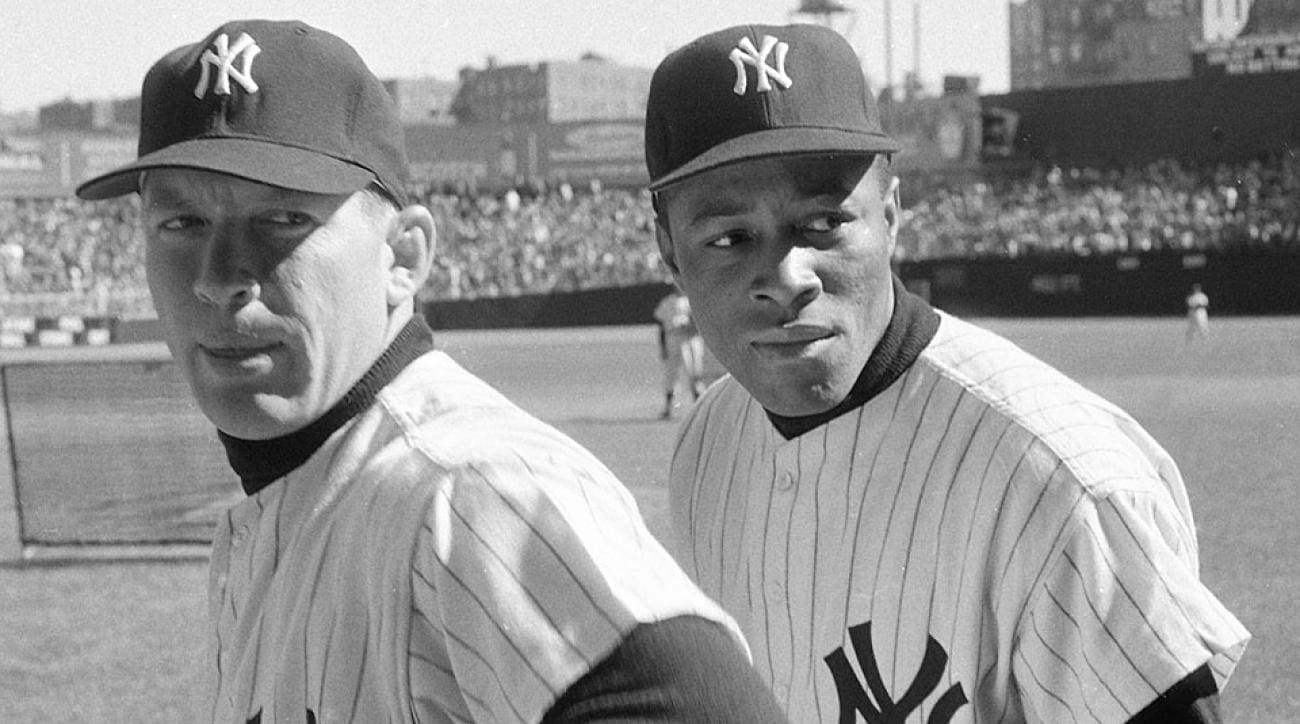

April 13, 1955 was a good day for the Yankees. They kicked off their season by trouncing the Washington Senators 19-1 in the Bronx. Mickey Mantle had three hits, including a home run; Yogi Berra also homered; and Whitey Ford threw a complete game while allowing fewer hits (two) than he had himself (three, plus four RBIs). But New York’s most significant player that day never got off the bench. Two days shy of eight years exactly after Jackie Robinson hurdled Major League Baseball’s color barrier, Elston Howard became the first African-American player to don Yankees pinstripes.

The delay by America’s most popular and successful team to integrate had led to everything from editorials to picket lines, all of which had been ignored by New York’s top brass. In his book, Baseball’s Great Experiment, author Jules Tygiel quotes general manager George Weiss as saying, “The Yankees are not going to promote a Negro player to the Stadium simply in order to be able to say that they have such a player. We are not going to bow to pressure groups on this issue.”

To be fair, New York’s roster didn’t have many holes in those years, not when the team was winning six World Series titles from 1947-54. But there were certainly weak links that could have been bolstered had the Yankees not been so slow to embrace integration. Howard’s debut made New York the 13th of the 16 major league franchises then in existence to employ an African-American player. Weiss had previously passed on opportunities to sign Ernie Banks and Willie Mays, among others, and comments from Yankees staffers suggested prejudice had factored into keeping the team’s lineup all-white.

In Baseball’s Great Experiment, traveling secretary Bill McCorry is quoted as saying of the then-19-year-old Mays, “The kid can’t hit a curveball” and, after Mays’ early success with the Giants, “I got no use for him or any of them. No n—– will ever have a berth on any train I’m running.”

As recalled in Roger Kahn’s seminal 1972 book, The Boys Of Summer, Weiss had said in 1952 that having a black ballplayer would draw undesirables to the Stadium. “We don’t want that sort of crowd,” he said. “It would offend boxholders from Westchester to have to sit with n—–s.”

Money was another factor behind the Yankees’ resistance to integrate. In August 1946, the team’s then owner and general manager, Larry MacPhail, chaired a special committee that reported to new commissioner Happy Chandler. The report stated, in part, “the relationship of the Negro player, and/or the existing Negro Leagues to Professional Baseball is a real problem,” in large part because MLB integration could cause the demise of the Negro Leagues. That, MacPhail’s committee noted, would cost teams like the Yankees the nearly $100,000 it netted annually from renting the Stadium to the Black Yankees, a Negro Leagues team.

Nevertheless, in late July 1953, New York seemed ready to call up Vic Power, a dark-skinned Puerto Rican who was tearing up the Triple A American Association with his hitting. Instead, Weiss surprised the press and fans by promoting Gus Triandos, a white player from Double A. “It would appear that the only advantage Triandos had was one of circumstance in not being born a Negro,” Joe Bostic wrote in The New York Amsterdam News.

Power was a strong hitter who was on his way toward winning the American Association batting crown with a .349 average. The Yankees seemed more concerned that he dated light-skinned women, a common convention in his native Puerto Rico but one that went against American social mores of the time. Weiss traded Power to the Philadelphia Athletics that winter. “Maybe he can play, but not for us,” Weiss is quoted as saying in Kahn’s book, The Era: 1947-57. “He’s impudent and he goes for white women. Power is not the Yankee type.”

The next spring, New York invited a strong-armed outfielder named Elston Howard to camp, where the team surprised him with the idea of converting him into a catcher. The Yankees already had an indomitable catcher in Berra, who that season would win his second of three AL MVP awards. Conspiracy theorists claimed this was a ploy for the team to submerge Howard in its farm system, and indeed New York assigned him to Triple A. The Baltimore Afro-American’s Sam Lacy characterized Howard as a “victim” and a “pawn” and quoted him complaining about his treatment. Howard denied the quote and asserted, “I ought to punch that guy’s head off.”

Howard made his biggest statement on the field, where he won the league MVP award that summer, earning a promotion to the Bronx for the 1955 season. He made his major league debut on April 14 in Boston, taking over in leftfield in the bottom of the sixth. He made his first and only plate appearance of the day in the eighth inning, lining a solid single to centerfield to score Mantle, though New York lost 8-4.

Howard didn’t make his first start until April 28, whereupon he went 3-for-5 with two runs scored and two RBIs in an 11-4 win at Kansas City. He played 97 games in all that season, finishing with a .290 average, 10 home runs and 43 RBIs and helping the Yankees reach the World Series. He then played all seven games of the Fall Classic—hitting a home run in Game 1—but he batted just .192 and made the final out of New York’s seven-game loss to the Dodgers.

In time, Howard would become a star himself. He won the 1963 AL MVP, helped the Yankees win nine pennants and four World Series and had his number 32 retired in 1984. But the prejudice he faced didn’t cease with his promotion to the majors. His manager, Casey Stengel, is quoted in Robert Creamer’s biography Stengel as calling Howard “n—-” and “Eightball.” Several of Howard’s teammates, however, welcomed the rookie. Moose Skowron picked him up at the train station; Hank Bauer invited him to join other players in the hotel dining room; Berra and Phil Rizzuto socialized with him.

Perhaps the most notable sign of his acceptance came a month after his debut. On May 14, he came to bat in the bottom of the ninth inning with two outs, two runners on and the Yankees trailing the Tigers 6-5. Howard laced a triple to left that scored Joe Collins and Mantle, giving New York a 7-6 win. When Howard reached the clubhouse, he found that Collins and Mantle had laid out an honorary carpet of white towels from his locker to the shower. He was officially one of their own.

© John Rosengren