Sourcebooks

Paperback, 2023

Nonfiction, 436 pages

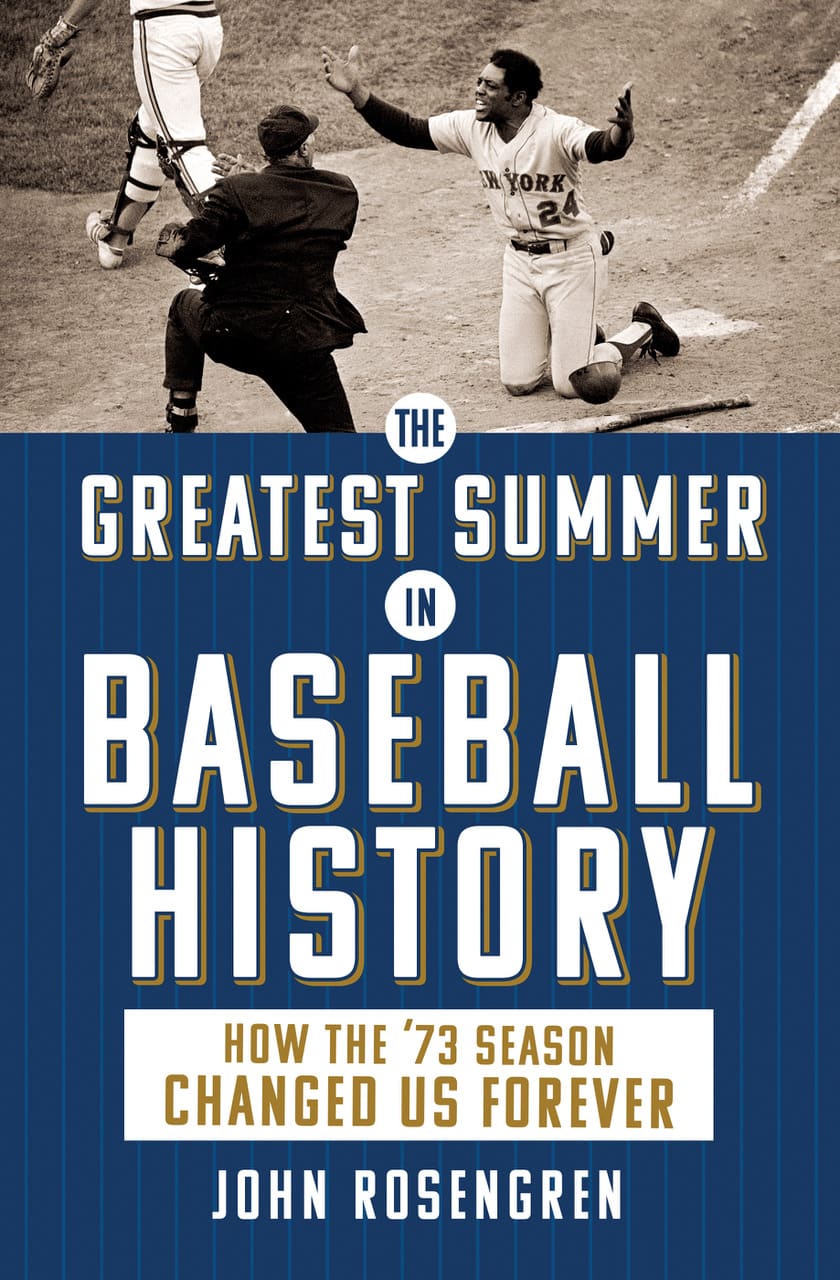

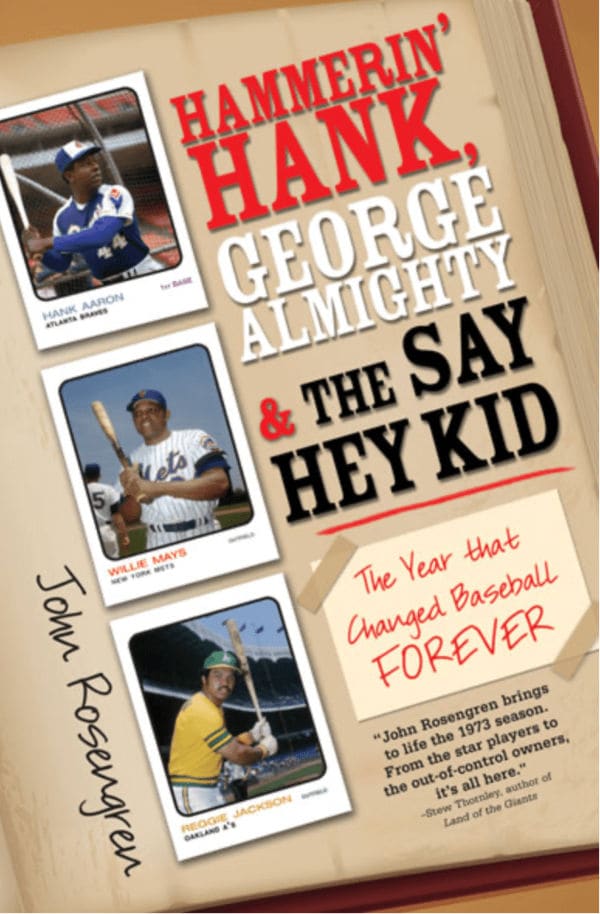

(originally published in 2008 as Hammerin’ Hank, George Almighty, and the Say Hey Kid)

1973. The U.S. pulled out of Vietnam. The Watergate hearings transfixed a record television audience. President Nixon tried to explain an 18-minute silence on the White House tapes. And the national pastime underwent an extreme makeover.

The summer of ‘73 served up a highly entertaining baseball season populated by some of the game’s greatest stars. It also marked a number of endings and beginnings that changed baseball forever.

George Steinbrenner bought the Yankees, beginning his influential, big money reign as king of America’s team. The American League introduced the designated hitter, adding offense to games and extending the careers of aging stars such as Orlando Cepeda. Hank Aaron chased Babe Ruth’s landmark 714 record in the face of racist threats. The Mets performed another near miracle, rising from last place in the National League East on August 30 to win the division and take the A’s to seven games in the World Series. The A’s established themselves as a dynasty with their second straight world championship. The Mets’ Willie Mays, arguably the best player of the ‘50s and ‘60s, hit the final home run of his career and retired, no longer able to keep pace with the younger players of the next generation, most notably Reggie Jackson, the World Series MVP, who began his tenure as Mr. October.

Hammerin’ Hank, George Almighty and the Say Hey Kid weaves together the stories of five men—Aaron, Steinbrenner, Mays, Cepeda, and Jackson—to animate the 1973 season and show how that watershed year forever changed the national pastime.

Author Interview

Q. What was the inspiration for Hammerin’ Hank, George Almighty and the Say Hey Kid?

JR. I really enjoyed reading David Halberstam’s “Summer of ‘49” and Tom Adelman’s “Long Ball” about the 1975 season. Those two books set me looking for a similar season of dramatic events that transformed the game. I found it in the ‘73 season.

Q. What’s the back story on writing this book?

JR. The research was so enjoyable. I spent hours at the downtown Minneapolis central library–which in itself is a pleasant experience–poring over Sports Illustrated, Sport magazine and The Sporting News. I used to subscribe to Sports Illustrated and Sport and remembered some of the specific articles and photos, not just about baseball but all of them. I was easily sidetracked by stories about Larry Csonka, Muhammad Ali, Bobby Orr, etc. It was a wonderful walk walk down Memory Lane.

Q. How’d you develop your love of baseball?

JR. My dad used to take me to games at the old Met Stadium. One wasn’t enough for us, so we would go to doubleheaders back in the day when they scheduled those. As often happens with fathers and sons, we bonded over baseball. When I hit my teens and my discussions with my dad about politics and society became more contentious, we could always agree on baseball. That became a safe neutral ground and mutual love for us. It kept us together.

Q. What has been the lasting impact of the ‘73 season?

JR. You’ll have to read the book for the full answer. In short, Steinbrenner infused big money into a team’s operating budget, the designated hitter rule extended the careers of many older stars and brought more offense to the American League, Hank Aaron infused the home run with an added measure of drawing power, and Reggie Jackson invented the modern superstar.

Q. Are you for or against the DH?

JR. I’m for whatever gives the game its intricate strategy. With all due respect to Jim Leyland, I don’t think the DH does that. The DH rule has also contributed to the emphasis on power, which has all but eliminated bunting from the game. I miss that. I admired bunting artists like Rod Carew. You could also say that the emphasis on power is the underpinning of the steroid era. Bunting specialists weren’t injecting performance-enhancing drugs.

Q. Anything you weren’t able to put in the book that happened that year?

JR. Lots. My boyhood hero, Rod Carew, won the batting title in 1973–the third of his seven–but he did not figure in the five major storylines. I wasn’t able to write about him other than a brief mention of racial taunts hurled at him after he stole home in a game in Arlington to illustrate the racially-charged atmosphere during that season. A catcher myself, I had a poster of Johnny Bench on my bedroom wall, but I was able to write about him only in limited ways that contributed to the story in the All-Star game and the National League playoffs. I could fill another book with stories about the players I admired from that year.

Reviews & Articles

A memorable book for a memorable season By Shawn Fury

The research that obviously went into this book would earn the

admiration of any historian, but it’s the vivid, engaging writing that makes “Hammerin Hank…” such an appealing read. For fans who remember the 1973 season, and those who weren’t even born yet, this book paints a picture with details and a story that live up to the title’s hype. The effects of many of the events from that season are still being felt today.

This was the year that George Steinbrenner took over the Yankees, and 35 years later the Boss, and now his son, continue to loom over the game. In the book, we read the type of Steinbrenner tale – him demanding that three Yankees get haircuts – that made him such an easy target, yet Rosengren also shows the lengths he’d go to to make the Yankees a winner, no matter the cost.

The DH went into effect in ’73, and years before chicks dug the long ball, Rosengren shows how Oakland owner Charlie Finley pushed for more offense in the game, believing it would bring fans back. The DH rule led Carl Yazstremski to say, “It’s legalized manslaughter,” because pitchers no longer had to worry about suffering the consequences if they beaned an opposing hitter.

1973 was Willie Mays’s final season. Today, whenever an older athlete struggles, it’s almost become cliche to say that he should retire because we don’t want to see him “stumbling around like Willie Mays.” Rosengren details exactly what happened to the baseball legend, and how he struggled through his final days on the field.

The book tells the big stories, as well as the memorable smaller ones – like Gaylord Perry’s spitball-throwing antics, and the tale of the two pitchers who switched lives, including wives. The story of the champion A’s, one of the game’s great dynasties, is perfectly profiled, as is the rise of their superstar, Reggie Jackson. And, of course, throughout the book is the tale of Hank Aaron’s pursuit of Babe Ruth’s home run record. He’d finish one dinger short of Ruth, and we’re there every step with Aaron – from the hate mail (275 letters a day at one point), to the remarkable fact that only 1,362 fans saw Aaron’s 711th career homer.

For those who might question whether 1973 really was the year that changed baseball forever, all they have to do is read this book, and they’ll be fully convinced that it did.

–amazon.com

This well-written, insightful and intriguing tome relates how the events of the 1973 baseball season, and several events that unfolded around it, really did change the game, and perhaps the country, for all time. Think about it:

* You had Hank Aaron chasing babe Ruth, right down to the last day of the season, contending not only with his aging body and racist death threats, but also the ambivalence of the baseball establishment (read: Commissioner Bowie Kuhn) and the people of Atlanta, who mostly ignored him right to the end.

* Willie Mays, the once great Giants centerfielder, was limping along in his last year as a player with the Mets, who somehow managed to get to the World Series despite winning only 82 regular season games.

* Reggie Jackson was trying single-handedly to not just win the AL pennant again, but to become the superstar that we all now know him to be, and while he was at it, he was also trying to change the way players dealt with both management and the media. He succeeded at all three.

* Pete Rose (this was before he bet on baseball, we assume) collected his 2,000th career hit, won his third batting title and his only NL MVP award.

* Charlie Finley was an odd juxtaposition of both progressive and traditional baseball values. For example, he lobbied for the Designated Hitter rule, which was accepted, as a way to improve offense levels in the attendance-challenged American League. He also suggested orange baseballs for night games, though these were only used in exhibitions. At the same time, he was a world-class cheapskate, losing his players’ loyalty (and in some cases their contracts) over comparatively trifling sums because he simply could not stand to give up a dollar if he didn’t absolutely have to.

* George Steinbrenner bought the New York Yankees for a song from CBS, and despite promises to keep building ships for a living, it was not long before he started meddling…and winning.

At the same time, America was still trying to get out of the Vietnam War, and the Paris Peace Accords were signed, though it would not be the end. By the end of the year, both the President and the Vice President were forced from office over separate political scandals, though Nixon made significant inroads with both China and the Soviet Union, helped to start the DEA, the Alaska Pipeline, and signed the Endangered Species Act, before he was forced to leave.

To his credit, Rosengren doesn’t try to cover all of that stuff in his book, but he does touch on some of the bigger issues (like Watergate) and how the baseball world could never be wholly insulated from the larger culture. Steinbrenner’s illegal campaign contributions to Nixon in 1972 were given special attention in the book, as was the effect of the investigation, and his eventual conviction, on his business with the Yankees). Rosengren also discusses the ways in which Steinbrenner almost immediately renegs on his promise to practice “absentee ownership” and “stick to building ships”, and apparently had no shame about the way he wanted to run things. When Mike Burke, the general Manager of the team under CBS’s ownership, was forced out, George simply explained that, “[he] didn’t agree with everything I wanted to do, so I fired him.” (p. 82)

Speaking of contentious and controversial owners, the Oakland Athletics, despite their success in 1972, were a wild bunch, and hated their cheapskate owner. “They disregarded authority with exuberant contempt.” (p. 29) Moreover, they nearly mutinied during the World Series when Finley’s meddling forced second baseman Mike Andrews to agree to a false medical report in order to get someone else on the roster. Finley eventually forced out his manager, Dick Williams, lost his best pitcher, Catfish Hunter, and the AL MVP Reggie Jackson, once free agency took hold.

Finley’s brainchild, the DH, was proposed essentially as a gimmick to improve attendance, which, it was though, would increase with increased offense. The American League in 1972 had averaged just 3.47 runs per game, 13% lower than the Senior Circuit, and almost exactly as low as the anemic 1968 season. Run scoring (and attendance) increased dramatically in 1973, and everyone was so pleased after only the first season of what was supposed to have been a three-year experiment, they decided to make the DH permanent. Hard to blame them.

Rosengren manages to relate some of the social and historical implications of the DH, the ways it was perceived and who actually embraced the role and succeeded at it. Ron Blomberg may have gotten his name in the record books as the first player to serve in the role, But Orlando Cepeda was the one who made the DH look like a good idea. Cha Cha was basically washed up at 35, but got a second chance in Boston in 1973 due entirely to the DH rule, and probably owes his Hall of Fame induction to it. (Rosengren mentions that Cepeda won the inaugural Outstanding DH Award in ’73, though he fails to include the fact that Frank Robinson had a much better season. Baby Bull only got the award because it was started by a newspaper in New Hampshire, which is obviously in Red Sox Nation.)

The book, in fact, is really quite good. The author seems to be one of those select few people who can look at an array of information from various and sundry sources and not only see the big picture, but relate it to others as well. It seems that a lot of things really did change in 1973, and Rosengren weaves all the intricate parts of that season together for you, presenting the tapestry and explaining how it all fits, and what it all means.

How he managed to do this is beyond me. His bibliography lists over 50 different books, plus numerous websites, periodicals, audio/video sources and more than a dozen personal interviews with players and other personalities who lived the events in the book. And talk about meticulous! After the brief first chapter, every chapter has at least 29 end notes, and most have at least 60! The man obviously paid enormous attention to detail, working his butt off to verify and cite his sources.

The result is an interesting, well-researched, well-written and comprehensive work that tells the tale of a season that really did change the world of baseball forever.

–from Travis Nelson’s Baseball Blog

www.boyofsummer.blogspot.com/2008/04/book-review-hammerin-hank-george.html

Rosengren is no stranger to sports controversy. In 2003, he published Blades of Glory, a critical look at the hypercompetitive Minnesota high school hockey culture; three years later, he co-wrote Alone in the Trenches, football player Esera Tuaolo’s memoir about his struggle as a closetted gay man in the NFL. Now Rosengren turns his keen journalistic eye toward race, money, and baseball politics, giving us a comprehensive account of the most tumultuous season in Major League Baseball history. He documents the triumphs of Reggie Jackson and Hank Aaron over racism and prejudice, the risse of billionaire Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, and the rule changes that occurred between the American League and the National League, concluding, “There will never be baseball like it was played in 1973.”

–Katie Koch, Bostonia

While many baseball fans likely have a casual knowledge of the subjects Rosengren explores in his latest effort, the depths to which the author travels gives new insight into the 1973 baseball season. Rosengren follows the season chronologically from opening day to the Oakland Athletics’ dramatic victory in the World Series, and while he discusses the issues that shaped the game, such as the advent of the designated hitter, more time is given to the personalities of the era. Plenty of fans can tell you that Willie Mays hit 660 career home runs, but Rosengren portrays a different side of the man whose arms and knees ached every time he set foot on the ball field. Rosengren also analyzes the Athletics, notorious for superstar Reggie Jackson but also Charlie Finley, an owner “famous for his megalomania.” And as for Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, Rosengren shows that the more things change, the more they stay the same. The author’s style is overexplanatory at times, and excessively breezy at others. However, the book is exhaustively researched, and for baseball fans not alive in 1973, an enjoyable history lesson.

—Publisher’s Weekly

Other books (e.g., Phil Pepe’s Catfish, Yaz, and Hammerin’ Hank: The Unforgettable Era That Transformed Baseball) have noted the 1970s as a crucible for change in baseball. Here, Rosengren narrows it down to 1973 with the vivid story of a young Reggie Jackson on Charlie Finley’s A’s and the veteran Willie Mays on Yogi’s Mets, both destined for the ’73 series. It was a season in which Hank Aaron, who avoided showmanship, attracted racist hostility as he busted the 700 mark in homers. There were many years that changed baseball forever, and this was certainly one of them.

—Library Journal

Readers Say

“The baseball bookshelves have long been heavy with memoirs of the 1950s, when today’s old boys were first taken out to the ball game. But a new generation of fans recalls the 1970s with all the pleasure and pathos that their fathers felt for the boys of summer. In this fine book John Rosengren presents the 1973 season as the pinnacle of the period between the expansion to divisional play and the revolution of free agency. In his telling, the story seems strangely modern, yet if it represents a new wave, it is that of “the new old.” He will find ready and willing readers.”

–John Thorn, author of “Baseball in the Garden of Eden”

“A wonderfully informative book that proves once again baseball reflects American culture more powerfully than any other sport. Indeed, John Rosengren’s book shows that sports are not an escape from political and social reality but a magnification of it.”

–Gerald Early, baseball historian and author

This isn’t just a book, it’s a season-ticket to one of the greatest years in baseball history. With a wonderful knack for capturing the spirit of the seventies and a crackling writing style, John Rosengren has given us one of the most enjoyable baseball books to come along in years.

— Jonathan Eig, author “Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig” and “Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season”

“John Rosengren brings to life the personalities and events that made the 1973 season a memorable one. From the star players to the out-of-control owners, it’s all here in Hammerin’ Hank, George Almighty and the Say Hey Kid.”

–Stew Thornley, author “Baseball in Minnesota: The Definitive History”

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: A Mr. October Afternoon

Chapter 2: The Money Game

Chapter 3: The Team of the Times

Chapter 4: The Designated Hitter Has His Day

Chapter 5: Chasing the Ghost

Chapter 6: The Cover-up Game

Chapter 7: One Up, One Down

Chapter 8: You’re So Vain

Chapter 9: Dear Nigger

Chapter 10: The Midsummer Classic

Chapter 11: Cheating

Chapter 12: Rah Rah for Cha Cha

Chapter 13: Love Atlanta Style

Chapter 14: Wrasslin’ Another Division Title

Chapter 15: Say Goodbye to America

Chapter 16: Pennant Fever

Chapter 17: A Classic Fall Classic

Chapter 18: Extra Innings

Excerpts

Hank Aaron

One could hardly mention Hank Aaron’s name in 1973 without hearing Babe Ruth’s. The prospect of Aaron passing Ruth’s monumental mark inevitably led to comparisons and debates over whose 714 homers were the greater accomplishment. The Ruthians contended that the Babe reached 714 in 3,000 fewer at bats than Aaron, slugging a homer on average once every twelve at bats to Aaron’s once every sixteen. In Ruth’s prime, from 1920 through 1933, they noted, he hit 637 home runs, an average of 45.5 per 154-game season; Aaron hit more than 45 home runs only once in the 162-game season.

The Babe dominated in a way Aaron didn’t. Ruth led the league in on-base percentage ten times (his .474 career mark is second on the all-time list); Aaron never did. Ruth led the league in slugging percentage his first thirteen seasons (his .690 career mark remains the best ever); Aaron led the league four times in slugging percentage (his .555 ranks 27th all-time). Ruth’s .342 lifetime batting average eclipsed Aaron’s .311 lifetime average. Babe Ruth, his loyalists maintained, was the greatest hitter of all time, bar none.

The Aaron camp countered that his soon-to-be 714 homers were hit under more difficult conditions. Aaron faced bigger, harder-throwing pitchers, many of them fresh relievers in late innings. He played night games when the ball was harder to see. He crisscrossed the country and multiple time zones on late-night flights and played day games after night games. He may not have led the league as often, but year after year–for twenty years straight–he performed consistently, not having a bad season. ”Real baseball people understand that the best thing you can have in a sport with a long season is consistency,” the syndicated columnist and baseball fan George Will noted. “Henry Aaron, by that measure, is the greatest baseball player ever, period, end of discussion.”

Aaron may have benefited from the lighter, thinner bats that players could whip around faster, but the bat’s smaller sweet spot required more precision in the swing. Some believed that Aaron also benefited from a livelier ball, but, in fact, the opposite was true. Ruth played almost his entire career in the “live-ball era,” which lasted from 1920 to about 1934, when the manufacturers deadened the ball somewhat. Changes to better stitching, binding and the core revived the ball in the Fifties. “The ball is livelier now than in the late Thirties and Forties but not as lively as in Ruth’s years,” baseball historian Joe Reichler, a member of the commissioner’s staff, told the Los Angeles Times in June 1973. Aaron himself pointed out that Ruth never had to face the likes of Bob Gibson, Juan Marichal and Ferguson Jenkins, because blacks were banned from Major League Baseball in his day. “Ruth may have had it easier for that reason,” Aaron wrote in I Had a Hammer.

In the end, nostalgia and legend seemed to tip most of the arguments in the Babe’s favor. More than half of the letters Aaron received still did not want to see him break Ruth’s record. “Of course, you had the man Hank Aaron and the myth Babe Ruth, and then the commercialized image of Babe Ruth,” Reverend Jesse Jackson opined. “It was just amazing that the myth of Ruth and this home run number was a kind of white supremacy symbol for many people.”

Certainly, Aaron faced pressure Ruth hadn’t in the form of hate mail, shouted epithets and death threats. There was also the invisible but palpable prejudice of apathy and indifference. Aaron felt that as well. Crowds may have doubled in other cities around the league where he played, but Atlanta fans ignored Hammerin’ Hank’s pursuit en masse. July 21, the day after Aaron hit No. 699, the Braves sold only 16,236 tickets to a Saturday game against the Phillies. Naturally Aaron wondered if people stayed away because he was black.

Orlando Cepeda

Along came Opening Day. That historic afternoon game at Fenway. Ron Blomberg beat Orlando Cepeda into the record books, but both of their bats were shipped to Cooperstown. Not that Cepeda had done much with his. There, too, Blomberg showed him up. The Yankees DH added a single to his walk, reaching base twice in four trips to the plate. The Red Sox had won big, 15-5, but Cepeda’s bat had been silent. Listed fifth in the Boston order, the Red Sox’s expensive designated hitter had come to the plate six times and walked back to the dugout six times without reaching base. He tried to beat out one ground ball–laboring, straining, barely moving–but was easily thrown out. It was painful just to watch. The 32,000-plus Fenway faithful shook their heads. Cepeda finished the first day of the experiment oh-for-six.

His second day did not go much better. In a replay of Opening Day, the sun shone impotently, the cold winds whipped, the Sox routed the Yankees and Cepeda went hitless. He did manage two sacrifice flies and a base on balls, but Boston wasn’t paying him the big money to hit long outs. After two games, the Red Sox had scored 25 runs on 33 hits, but the team’s designated hitter hadn’t contributed one hit. Cepeda was oh-for-eight, and doubts about the DH experiment loomed large as the triple zeros in his batting average. Boston fans taunted him from the bleachers. Sportswriters tagged him the designated out.

The mockery continued on day three. Once, twice, thrice, Cepeda failed to hit. Kasko had stuck with Cepeda in the number five spot, but he decided he would sit Cha Cha tomorrow and use Ben Oglivie. Cepeda came to bat again in the ninth oh-for-eleven on the season. His knees ached in the cold. He didn’t think he could run. He would be lucky to beat the throw to first if he banged a ball off the Green Monster.

Cepeda faced Sparky Lyle, on the mound in his first appearance at Fenway since the Red Sox traded him to Yankees a year earlier. Lyle had come into game three innings earlier, trailing 3-2, but the Yankees had evened the score in the top of the ninth. He wanted to give his team a chance to bat in the tenth and avoid being swept by their hated foes. Even more, Lyle wanted to show the Red Sox what a mistake they had made in letting him go.

Cepeda watched Lyle’s first pitch. Ball one. He watched the second. Strike one. The pressure mounted. Lyle threw a slider, his money pitch. Cepeda swung–and connected. The ball lifted into the wind and muscled its way over the tall left-field wall. Home run! Boston 4, New York 3.

The Fenway crowd “erupted into a frenzy.” Cepeda’s teammates rushed out of the dugout to congratulate him at home. Cha Cha stopped short of the plate, then toed it with his right foot in a celebratory dance step. His teammates mugged him happily.

George Steinbrenner

Bill Singer wasn’t the only pitcher throwing spitballs that summer. George Steinbrenner suspected Gaylord Perry was also illegally greasing the ball. Singer and Perry weren’t the only suspects, but they were the most visible and most successful, particularly Perry, who won the 1972 AL Cy Young Award with a 24-16 record. The thirty-four right-hander had been accused countless times of doctoring the ball with sweat, grease or spit but never been convicted. The Boss was determined to catch the purported cheat when Perry and the Indians came to Yankee Stadium in late June.

Perry had beaten the Yankees 4-2 in Cleveland on June 25 and ended their wining streak. Convinced that Perry was loading the ball, manager Ralph Houk impulsively rushed to the mound in the eighth inning after Perry’s first pitch to centerfielder Bobby Murcer. Houk tugged off Perry’s cap, threw it to the ground and kicked it.

Murcer bunted the next pitch foul down the third-base line. Third base coach Dick Howser picked up the ball and rushed to show umpire Lou DiMuro what he believed was grease smudged on the ball. DiMuro was not convinced. He ejected Howser for his animated and impolite argument.

Later, Houk summoned DiMuro to the mound to search the pitcher. This time, Perry cooperatively removed his hat for inspection. They found nothing.

After the game, Murcer criticized commissioner Bowie Kuhn and American League president Joe Cronin for letting Perry get away with throwing his spitball. “If the league president or commissioner had any guts, they’d ban the pitch,” he said.

The team, it seemed, was starting to behave like its owner, whose behavior The New York Times had characterized as “sometimes questionable.” For his part, Steinbrenner told the press that he had authorized the installation of two closed-circuit TV cameras to be trained on Perry throughout the Friday, June 29, game at Yankee Stadium. Yankee president Gabe Paul, recently of the Cleveland Indians, had hatched the surveillance plan to catch Perry in the act of doctoring the ball through the slow-motion and stop-action replay of the film. The team invited the league to send an official to watch the film with them.

Steinbrenner approved the plan. If the guy was cheating, The Boss figured he deserved to be caught and punished. He would see to it himself. The irony of Steinbrenner trying to catch a pitcher greasing a baseball while he covered up his illegal contributions to Nixon’s campaign was lost on George. Justice would have its day.

Willie Mays

On Saturday, June 9, the Mets staged an old-timers game before they hosted the Dodgers at Shea Stadium. A crowd of 47,800 turned out to watch past Mets’ greats play legends from the Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers, but it was Willie Mays, older than a dozen of the old-timers, who put on a show in the game that mattered. He started in center field for the first time at home in over a month. In the top of the third inning, with the scored tied 2-2, he made a tumbling circus catch. In the Mets’ half of the inning, Willie homered to put his team ahead to stay. As he had done so many times before, he won the game with his glove and bat.

Yet, these days, his feats served more to measure how far the hero had fallen. His spectacular catch would have been routine in the old days, but he initially misjudged the straightaway fly to center. Finally picking up the ball’s flight, he backpedaled in time to make the catch over his head, then fell backward and rolled twice across the dirt track at the wall. His home run was the 655th of his career, but only his first since the previous August, a four-month drought. Willie had become more memory than performing legend.

The game two days later, when San Francisco came to town on Monday evening, June 11, showed how low he had slipped. Mays started in center field for the third game in a row, “an endurance test he hadn’t tried in six weeks,” the Times noted. The fourth inning “exposed one of the Achilles heels that have [sic] bedeviled them (the Mets) this season: Willie Mays can’t throw,” Joseph Durso, who covered the Mets for the Times, observed. Mays chased a ball to the wall in left-center, nearly 400 feet from the plate, but, rather than heave it back to the infield, he lobbed the ball ten feet to rookie left fielder, George Theodore, to relay in. Theodore was so startled by Mays’ unusual move that he bobbled the ball, and the runner advanced to third. Mays drew an error on the play. In the bottom of the ninth inning, Mays came to the plate with the Mets trailing 2-1 and the tying run on first. He grounded out to second base to end the game and drop his batting average to .094. The man who had batted over .300 ten times wasn’t hitting half his weight.

The June 11 game prompted Roger Angell to remark in the New Yorker, “The horrible truth of the matter was that Mays was simply incapable of making the play (in the field) . . . his failings are now so cruel to watch that I am relieved he is not in the lineup every day.”

Reggie Jackson

Reggie scored his first hit of the national spotlight when he challenged Roger Maris’ single-season home run mark in 1969. Reggie hit 37 homers by the All-Star break. By September 1, he had hit forty-five. The media swarmed him, and everyone from the President to the team owner fawned over him. In the two weeks before the All-Star game, reporters demanded a hundred interviews. Sports Illustrated featured him on its cover in July. President Nixon sent him a personal note after Jackson hit two homers in a game Nixon attended in Washington. Reggie’s teammates stood to cheer him when he walked into the clubhouse after a Friday night game in Boston where he hit three home runs, two singles and a double, driving in ten runs. On July 2, in Seattle, after Reggie hit three homers in a game, Finley wrapped him in a hug. The attention and adulation intoxicated Reggie.

But he overdosed on it. The pressure attendant to such attention stalled his home run drive and landed him in the hospital with a case of shingles in September. He hit only two more homers that month and finished the season with forty-seven, third in the league. No matter. In only his second season, his early hot streak had catapulted his status from potential star to proven superstar. He wanted more of the fame trip.

His style reflected his ego. Fans today have become accustomed to players thumping their chests or watching their home run blasts like little boys enamored by their own turds, but in 1973, fans expected players to trot around the bases modestly with their heads down, the way Frank Robinson, Harmon Killebrew, Hank Aaron, et al did. But Reggie couldn’t contain himself that way. He shouted, pumped his arms or otherwise hot-dogged it around the bases when his turn came. Look at me!

Reggie worked the press to keep his name in the paper. “One of the things Reggie figured out early on was that he was an entertainer,” his teammate Joe Rudi said. “Playing in Oakland, he was playing in relative obscurity. He was doing everything he could to build up a national image.”

The media lapped up Reggie’s lip and lavished him with their attention. In the cliché-addled world of professional sports, where some athletes were dumber than a bag of laundry, here was a guy with an IQ of 160 willing to speak his mind. They could count on Reggie for good copy. Reggie had learned to work them and seemed to approach every interview as a chance to add another plank to the national platform he was building. These days, Sports Center, YouTube and fan blogs can catapult a player to national celebrity instantaneously, but in 1973, the opportunities were more limited. A player could make a name for himself with a tremendous performance on a nationally-broadcast “Game of the Week,” in the All-Star game or in the World Series. Reggie did all that and served up a generous portion of quotes. Bergman, the A’s beat reporter, tagged Reggie his MVQ, or Most Valuable Quote. Reporters in other cities soon discovered Reggie’s loquacious quotient and sought him out.

Even when he didn’t play, the reporters flocked to him, which provided more fodder for his teammates’ jealousy and resentment. In the 1972 World Series, the television cameras trained on the injured Jackson sitting with his crutches on the bench, and sportswriters asked his views of the games. When the A’s captured the Series crown, Reggie spoke for the team in the clubhouse. He proclaimed the start of a new dynasty.