On a Sunday afternoon in late February, I’m waiting for Herschel Walker. Outside the Springs Cinema & Taphouse, where he’s scheduled to take part in the Republican Jewish Coalition of Atlanta’s “job interview” of U.S. Senate hopefuls. It’s invitation only, closed to the news media — a point the two middle-aged women standing sentry in front of Theater 4 reiterated to me. This, per a directive from Walker’s campaign, was a condition of his participation.

I’ve scouted out back entries Walker could sneak in the way he has in past appearances. So far, his campaign staff had ignored my multiple requests for an interview. He’d talked only to conservative outlets like Fox News and Breitbart. Not finding another way in, I’m on a bench by the entrance.

Walker, the former football superstar endorsed by Donald Trump, has a seemingly insurmountable lead over fellow GOP contenders and is expected to win his party’s nomination in the May 24 primary. He’ll face stiffer competition, though, in the general election come November against the incumbent, Democrat Raphael Warnock.

I’m here, in part, because I want to see for myself if Walker’s campaign in Georgia reflects the nation’s new norm in post-Trumpian politics. Can enough celebrity sparkle and Trump rhetoric, coupled with some distortion of facts and often a general indifference to the particular needs of constituents, truly be the reality in GOP politics?

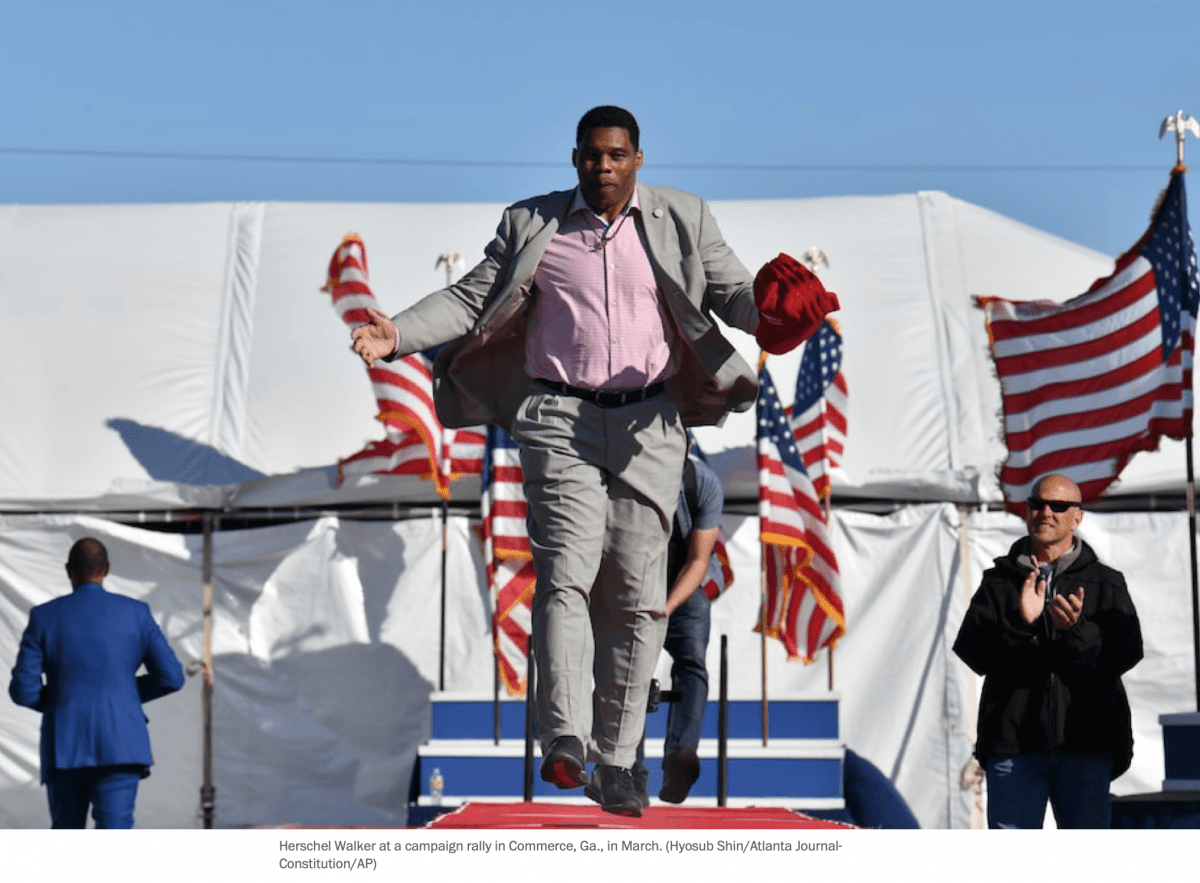

So here I am, and then there he is. Walker rides shotgun in the black GMC Yukon that sidles up to the cineplex. He climbs out, slides a blue sport coat over his black T-shirt and — flanked by his wife, Julie, and an aide — makes his way slowly up the steps. Two weeks shy of his 60th birthday, he shuffles like someone tackled too many times. I follow. Soon as he’s in the lobby, people recognize Georgia’s most familiar face and swoop in for selfies. Beloved as their football hero, he’s also been a track star, Olympic bobsledder, Fort Worth Ballet guest dancer, business owner, mixed martial arts fighter, taekwondo black belt and Food Network cooking show contestant.

After his 30 minutes behind closed doors, Walker works the crowd back in the lobby — posing for more selfies, leaning in to listen, maintaining steady eye contact — until by chance he is standing next to where I’m seated at the bar. I introduce myself. He shakes my hand with a surprisingly warm and soft grip and says, Yes, he will sit for an interview with me while I’m in town. His aide gives me phone numbers of contacts in Wrightsville, Walker’s hometown.

The older guy sitting next to me, a retired physician and a greeter for the event, had earlier barked at me after learning I was a reporter, “This is a private event. Get out of here.” (I reminded him the bar was a public place.) Now he tells Walker, “I don’t need a photo with you. I’ll wait until you’re a senator.”

To understand this race, you have to know the space Walker occupies in the hearts of potential voters. “This guy’s a god in Georgia,” Shelley Wynter, a radio host on Atlanta’s conservative talk station WSB, told me. “I don’t think people who don’t live in Georgia understand that.”

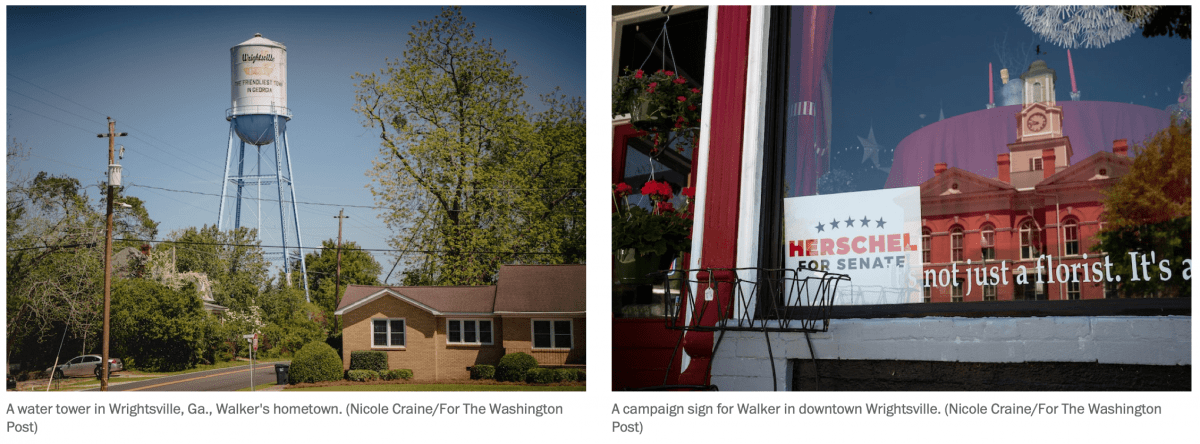

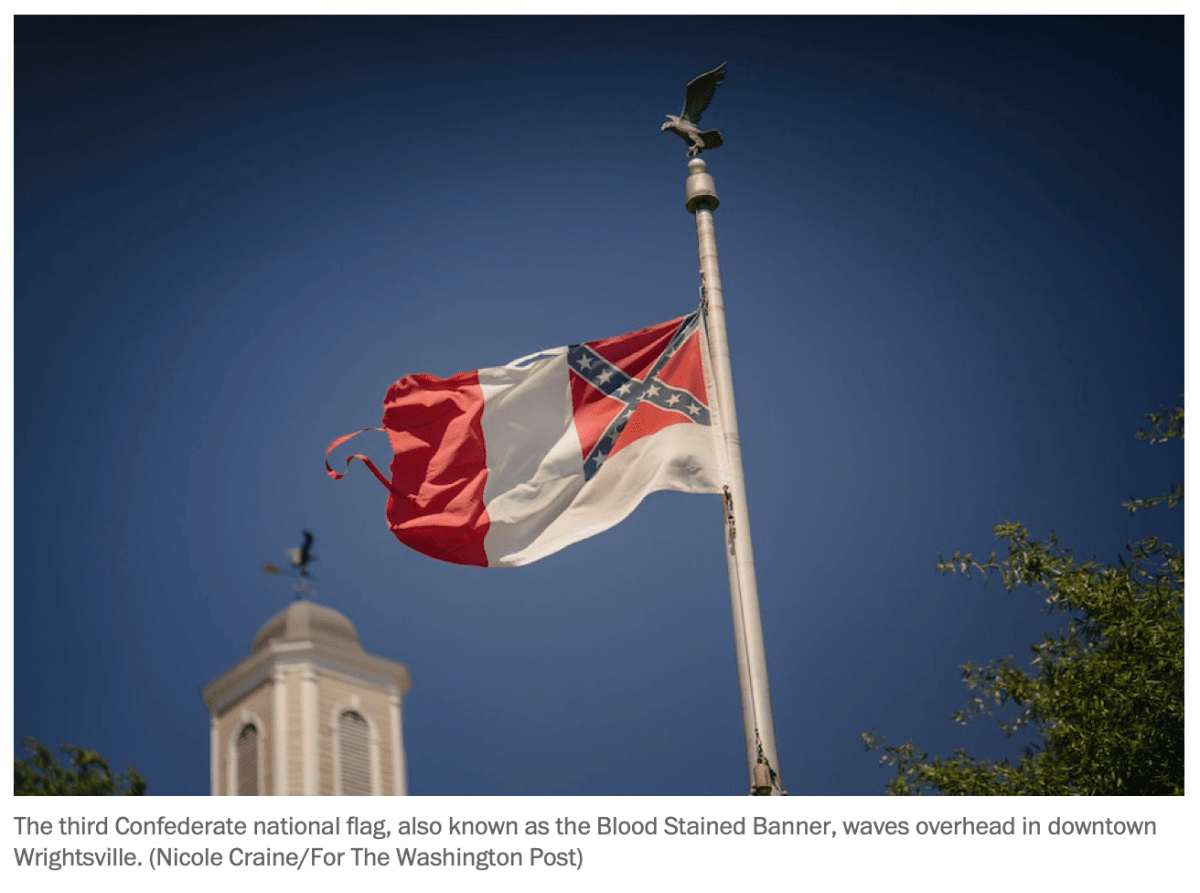

Walker was born in Wrightsville, Ga., a crossroads connecting several rural counties, where Confederate and Trump flags still wave. It’s a community of 3,600 named after an enslaver; a remote place where once clothing factories and kaolin mines provided jobs, but now a quarter of the storefronts among its four-block business node are shuttered. It’s also a town where the 110 students in Walker’s 1980 senior class at Johnson County High School were evenly split between Black and White, but racial tensions thrust Walker in the middle.

Head south for five miles until you reach a long drive on the left that rises to a single-story clapboard house amid large pines. This is where Willis and Christine Walker, who met picking cotton, raised their seven children, Willis pulling double shifts in the kaolin plant and Christine working her way up to supervisor at the garment factory. They christened their fifth child Herschel Junior but called him “Bo” at home. (He would later build his parents the larger brick Colonial you see today on the property that has expanded to 25 acres, including the building where Walker stores 45 antique cars and a Harley-Davidson.)

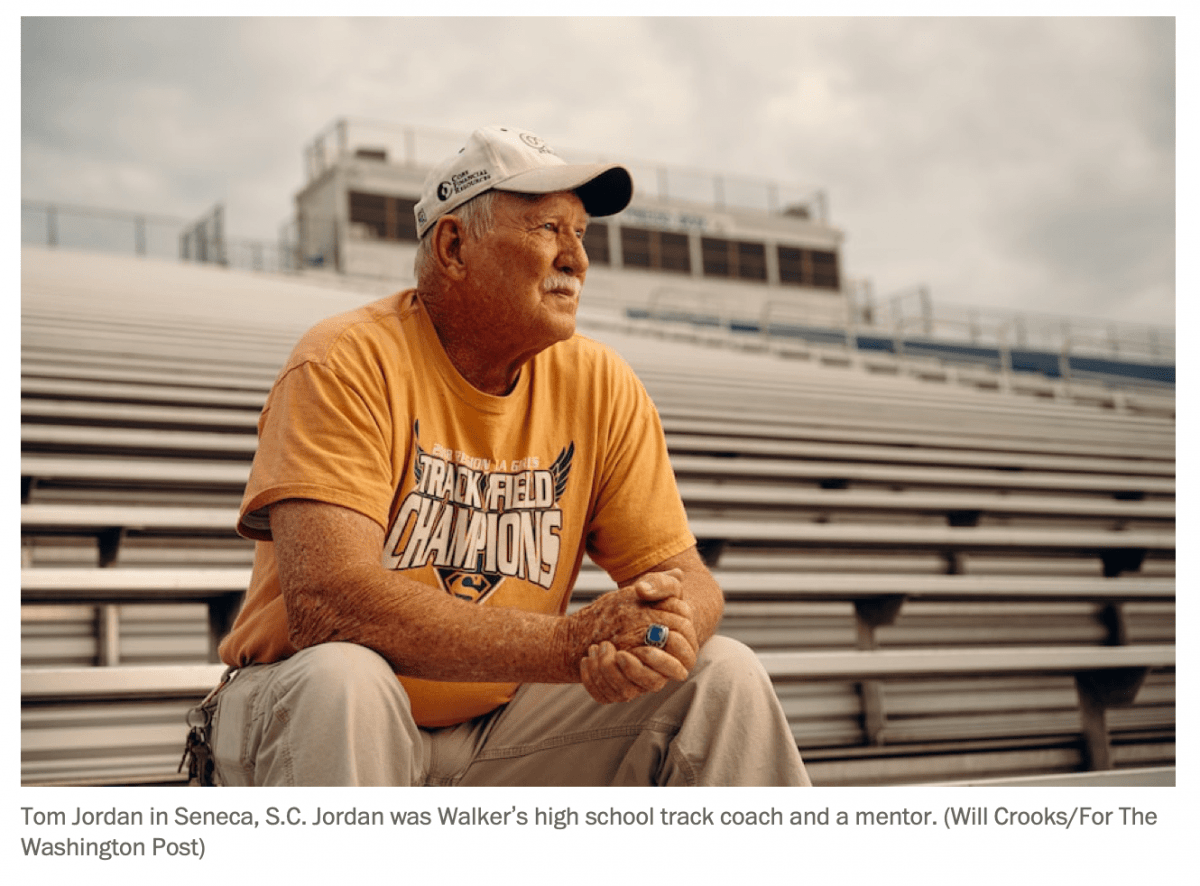

The boys were built like rocks, like their father. The two older ones, Willis Jr. and Renneth, may have been better natural athletes than Herschel, but they lacked his drive. He did 5,000 sit-ups and 5,000 push-ups every evening, he says, during commercial breaks of his favorite television shows. He ran laps on a path his father cleared for him and, later, the five miles to town — and back. At track practice, he dragged a tractor tire his coach loaded with 10-pound shots. “I never had a kid with his drive,” says that coach, Tom Jordan. “He was the most focused kid I ever dealt with in 51 years of coaching track and football.”

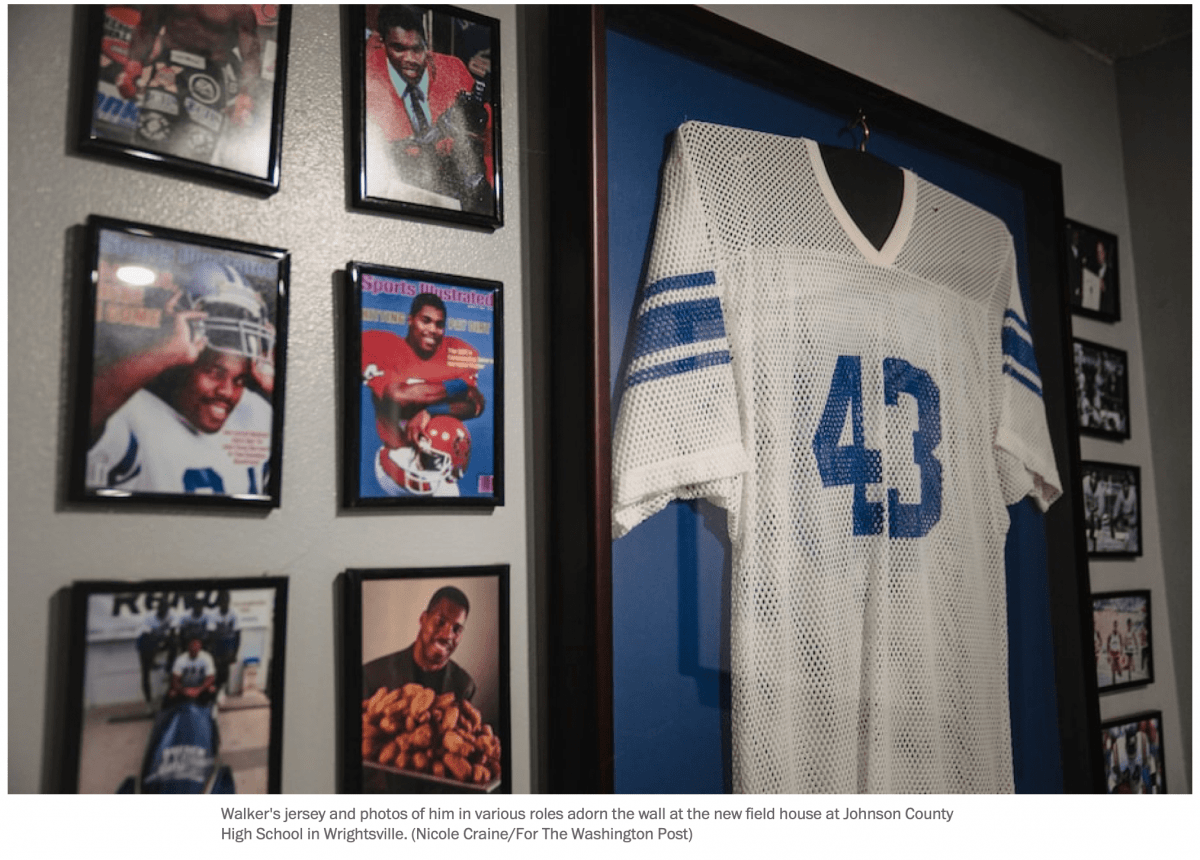

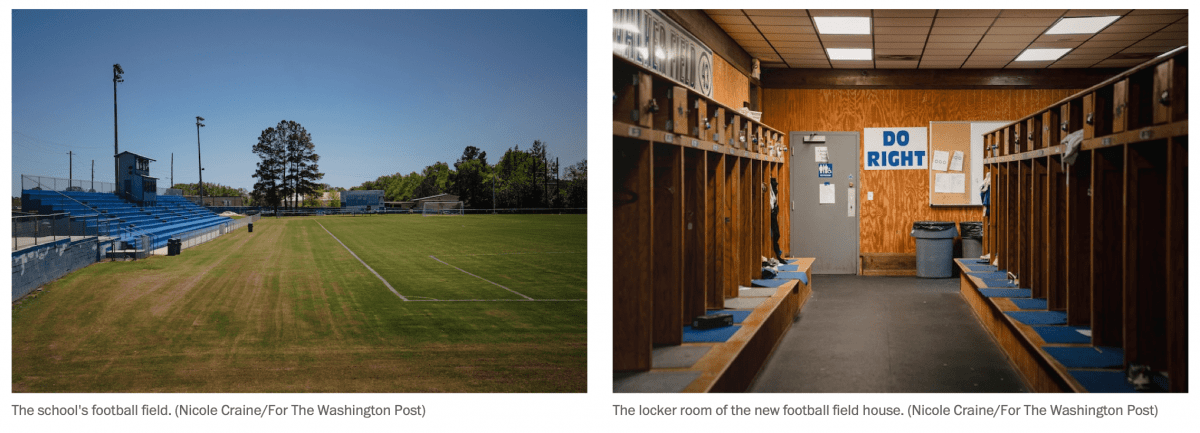

Walker was state champ in the shot put and 100-yard dash. He also lettered four years playing basketball. But it was at what is now Herschel Walker Field where the townspeople gathered Friday nights, cramming the concrete bleachers and ringing the football field, to marvel at the 6-foot-2, 210-pound man-child performing herculean feats. In high school, he ran for 6,137 yards and scored 86 touchdowns — more than half of each his senior year — set a school record for tackles as a linebacker and led the Johnson County Trojans to the state championship. The school promptly retired his jersey number, which now hangs in the field house, and later the street outside was named after him.

Heralded as the nation’s best high school running back by Parade magazine, Walker became the most desirable college prospect in the country. He ultimately chose the University of Georgia in Athens, 100 miles up State Route 15, where he burnished his legend. There he broke the NCAA freshman rushing record and powered the undefeated Bulldogs to the Sugar Bowl on Jan. 1, 1981. On his second carry, Walker dislocated his shoulder, but a doctor on the sidelines popped it into place. Despite the teeth-grinding pain, he carried the ball another 30 times, ran for 150 yards, scored two touchdowns and, as the game’s Outstanding Player, secured victory and the national championship for Georgia. “That was a miraculous performance,” says Loran Smith, a University of Georgia sports historian. “Nobody ever played hurt better than Herschel did in that game.”

With his world-class speed and amazing strength, Walker outran defenders or ran over them. In his second season he broke the NCAA rushing record for sophomores and brought his team to within 42 seconds of another national title. In his junior year, his third season as an all-American, he won the Heisman Trophy. “He was no longer just an all-American or a superstar — he was a legend,” the narrator gushes in a 2014 ESPN documentary about Walker.

Walker would be enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame and called by some the best collegiate football player ever. After only three seasons, his 5,259 yards rushing ranked him third all-time.

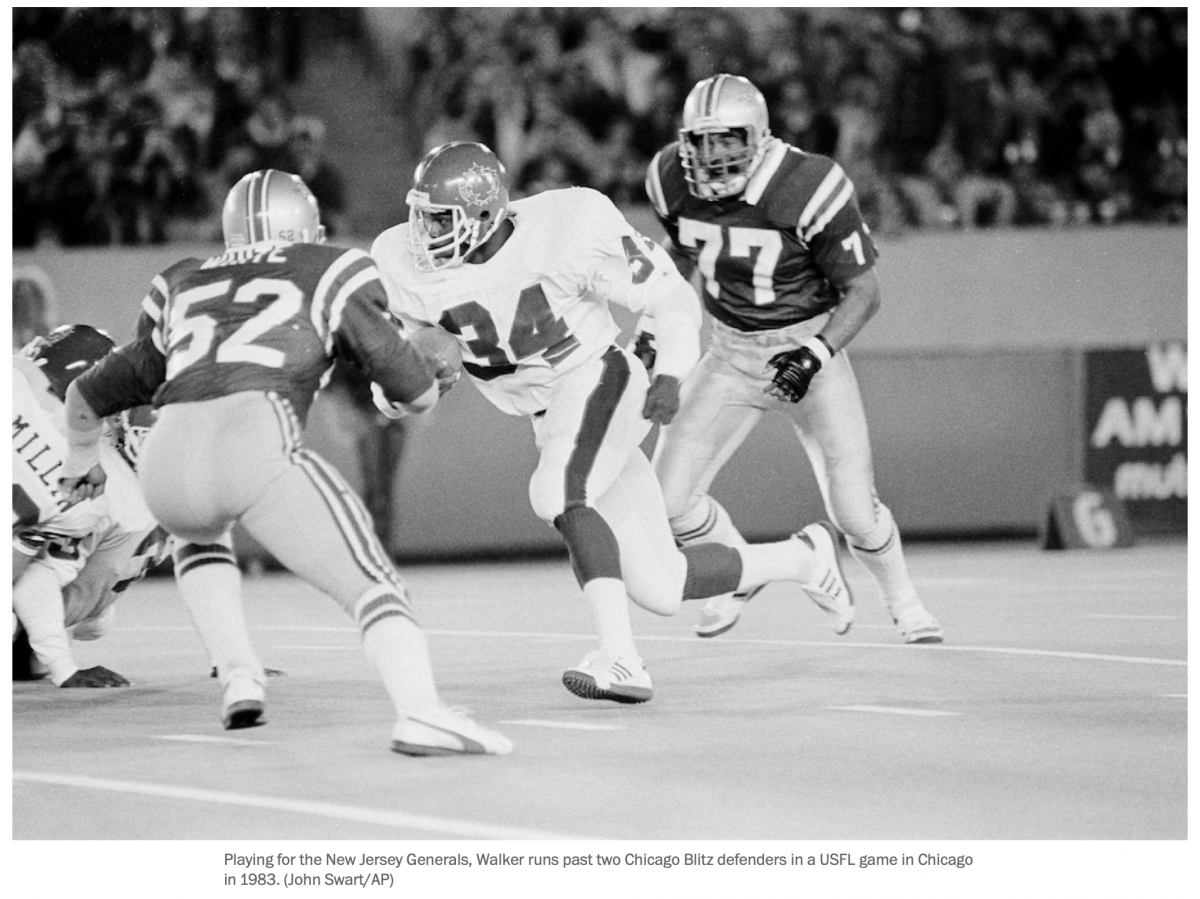

In an era when it was unthinkable for a college player to leave early, Walker signed a $4.2 million contract with the upstart United States Football League, making him the highest-paid professional athlete of the day. It would be three years before he began his 13-year NFL career, not until he was drafted by the Dallas Cowboys and the USFL folded.

In Georgia, Walker’s popularity seems to have only grown over the years. At a home game reuniting the 1980 Bulldogs team this past fall, the student section took up the chant, “Herschel! Herschel!” — just like old times.

A March Fox News poll of Republican primary voters in Georgia found Herschel Walker far ahead of other candidates, with 66 percent support, compared with single-digit support for other candidates.

The devotion of his followers runs deep. Take Sue Hall, who graduated in Walker’s class, still lives in Wrightsville and appears in one of his campaign commercials. When asked about Walker’s violent past, including allegations that he threatened to kill his ex-wife, she told me, “He’s probably like every one of us; he’s had his issues and had to grow. All of us have to adjust.”

When I said, “Yes, but most of us haven’t threatened to kill someone,” she responded, “I believe in him. He’s a moral person. Even if he were not a former classmate, I’d vote for him because of his values.”

The night after the Republican Jewish Coalition event, Walker is in Dahlonega, an hour drive north of Atlanta and county seat of Lumpkin County — a very White and poor county — for a fundraiser. A crowd of 150 has paid $20 apiece and filled the parks and rec gymnasium. In Walker’s 35-minute speech he works the crowd’s emotions, telling stories about his mother, how he loves the flag and that communists imprison Christians — “Do you want a government like that?” He demonizes Warnock — “He’s a reverend but he believes in abortion!” — and President Biden, and he mocks the news media “that don’t want to tell the truth.” He also makes false statements, such as “Do you know 70 percent of the drugs coming into America go through Atlanta?” When Walker proclaims, “America does come first!” a man seated behind me shouts, “Alleluia!”

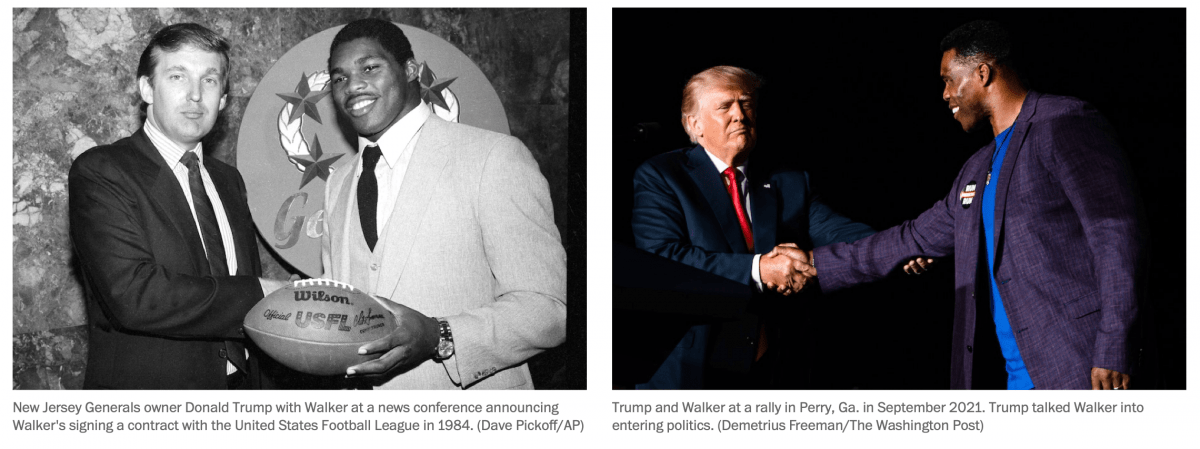

The performance echoes a Trump rally, which isn’t surprising since it was Donald Trump who encouraged Walker to get into politics in the first place. The two have known each other since 1984, after Trump bought the USFL team that lured Walker away from Georgia. Thinking of quitting football, Walker turned to the new owner for advice, and Trump, not wanting to lose his team’s star and the league’s marquee player, talked him into staying. “Mr. Trump became a mentor to me,” Walker writes in his 2008 memoir, “Breaking Free,” “and I modeled myself and my business practices after him.”

“I want to be a leader like [Trump] when I get to that Senate seat to show everyone I love America,” Walker says.

They maintained a friendship, traveling together on occasion with their families. Walker backed Trump early in his first presidential campaign and said in a video played at the 2020 Republican National Convention, “Most of you know me as a football player, but I’m also … a very good judge of character,” before extolling Trump’s moral fiber.

So when Trump said in a statement in March 2021, “Run Herschel, run!” Walker answered the call. At a rally in Perry, Ga., on a Saturday afternoon in September, many in the audience wore red MAGA-knockoff caps with the slogan “Run Herschel Run” and greeted their favorite son with the Bulldog chant “woof, woof, woof!” When Trump took the stage, he called Walker up to “say a few words,” seemingly unaware Walker had already given a nine-minute speech. Walker awkwardly obliged, expressing his fealty to Trump and ending by telling the crowd, “I want to be a leader like him when I get to that Senate seat to show everyone I love America.”

Georgia has become a personal battleground for Trump, still bitter about losing the state in 2020. He has not only backed Walker to regain the Senate seat Republicans lost to Warnock in a runoff election in January 2021, but he has backed David Perdue — who lost his Senate seat to Democrat Jon Ossoff in the state’s other runoff election — to oust Gov. Brian Kemp. After the 2020 presidential election, Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger rebuffed the president’s admonition to find 11,780 votes to reverse Georgia’s electoral results (a grand jury in Atlanta is investigating Trump’s action). Trump was back for another rally in March, this one in Commerce, to support seven candidates, including Perdue and Walker. Trump renewed his attack on Kemp but fretted, “If Kemp runs, I think Herschel Walker is gonna be … very seriously and negatively impacted. … A vote for Brian Kemp, RINO, in the primary is a vote for a Democrat senator who shouldn’t be in the Senate.”

So is Trump exploiting Walker to slake his personal vendetta? “[Walker] has positioned himself into being a useful fool for those who don’t have the best interests of Black people or this democracy at heart,” says Harry Edwards, a sports sociologist, civil rights activist and professor emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley.

It’s not clear how much Trump’s support will serve Walker, though. An Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll published in late January found 42 percent of Georgia Republicans said that a Trump endorsement would make them more likely to support a candidate, while about as many — 43 percent — said they were unsure and the remaining 15 percent said they would be less likely to vote for a candidate with a Trump endorsement.

In the January 2021 runoff for the two U.S. Senate seats, Trump’s picks both lost to Democrats, in part because his baseless complaints about not being able to trust the election process seemed to discourage some Georgia Republicans from voting. Those same voters could stay home in this November’s general election.

What’s more, a significant number of college-educated White male voters in Georgia who cast their ballots for Trump in 2016 did not do so again in 2020. The popular wisdom is that Walker will need their support to beat Warnock. While that might be possible with Biden’s slumping favorability, Trump’s stumping for Walker could, in fact, hurt his chances. “Trump is going to be all over Georgia,” says Charles S. Bullock, a professor of political science at the University of Georgia. “The more they’re reminded of what they don’t like about Trump will make [winning them back] problematic.”

Several days after I met Walker at the Republican Jewish Coalition event and he told me he would sit for an interview, he called to say he’d changed his mind. “Someone overheard you say you didn’t think I could win this thing,” he explained.

I hadn’t said that, but he couldn’t be convinced otherwise. Regarding Walker’s chances of winning the general election, many Republicans worry that Warnock, with his superior oratory skills, experience as a senator and knowledge of the issues, will eviscerate Walker if he does win the Republican nomination and agrees to debate Warnock. Says Wynter, the radio host, “The overwhelming fear is that he wins the primary and flames out in the general election.”

Right now you’re teaching kids critical race theory,” Walker tells the mostly White audience in Dahlonega. “I don’t even know what that is.” They laugh.

“I just found out the other day I was Black.” They laugh louder.

But race has not been a laughing matter for Walker. His senior year of high school (1979-1980), racial tensions roiled Wrightsville. A pastor led weekly marches on the courthouse to protest the lack of Black people employed by the sheriff and local businesses, and to demand sewers and roads in Black neighborhoods be repaired. On one occasion, a mob of White residents assaulted the marchers, who later claimed the sheriff had joined the attack. Another night, a suspected member of the Ku Klux Klan fired a shotgun into a Black teacher’s trailer home from his pickup, striking a girl inside. On yet another night, the sheriff raided a Black neighborhood and arrested 38 men and women, though none were convicted of any crime.

The tensions inevitably reached the high school, where one day six Black students pulled a jacket over the head of a White boy and beat him up. The two starting guards on the all-Black basketball team were suspended after a fight with White students. One day White parents stormed the school to demand their children come home. Georgia State Patrol troopers were sent in to keep peace. Nine of Walker’s track teammates quit the team as part of the protests. The Black activists implored Walker to join them, but he demurred, in part dissuaded by his track coach. “I told him, ‘Herschel, we have practice at 3 o’clock,’ ” Tom Jordan says. “You got to be here. You can’t be [leading marches].”

Walker’s refusal to use his national platform to advocate on their behalf alienated him from some of his Black neighbors, which he resented. “I never really liked the idea that I was to represent my people,” he writes in “Breaking Free.”

That stance — especially now, coming from a Senate candidate — has drawn sharp criticism from Black leaders. “Herschel Walker won’t advocate for anybody, only for what’s in his best interest,” Harry Edwards says. “He’s irrelevant to the Black community, and we should treat him as such.” A representative from Walker’s campaign declined to address the comments.

But Walker might be impossible to ignore, calling the leaders of Black Lives Matter “trained Marxists” who don’t believe in American values, mocking the defund police movement as the brainchild of a drunk and testifying at a congressional hearing in 2021 against reparations for slavery. He maintains that racism is a relic of the past, telling the congressional committee, “Slavery ended over 130 years ago,” and telling Glenn Beck in an interview the year before, “Racism is going back to the old days.”

Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter Fund, says that Walker is “a clear and present danger to our health and democracy.”

“This is a person who has run away from issues of race and has not dealt with them,” says Kevin Harris, former executive director of the Congressional Black Caucus. “If you are Herschel Walker and don’t understand how the racists are using you to give cover to their racism, then you are not qualified to serve in the U.S. Senate at this time.”

As such, in the general election against Warnock — a liberal champion of civil rights who inherited the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s pulpit at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta — Walker is not expected to curry many votes from Black residents, who make up nearly a third of voters in the state and are predominantly Democrats. He might not even carry Wrightsville. Walker “expresses too many views supportive of the past president,” says Curtis Dixon, a former neighbor who taught Walker world history in 10th grade and coached football. “He doesn’t have his finger on the pulse of the Black community.”

At the Dahlonega fundraiser, Walker tells the audience, “The criteria for running for office in the United States should be you love America. The second should be you love the Constitution.” Those beliefs pretty much sum up his platform — that, and his love for Jesus. He pledged to the crowd in Dahlonega, “When I go to Washington, Jesus is coming with me.”

Walker has not delivered any clear strategies for addressing the four top issues Georgia voters identified in the January Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll — elections, the economy, the pandemic and crime — other than to make broad statements, such as supporting the police and that inflation is too high. When he does get specific, it can get bizarre.

At a church in Sugar Hill, Ga., Walker said in March, “At one time, science said man came from apes. Did it not? Well, this is what’s interesting, though. If that is true, why are there still apes? Think about it.”

In August 2020 Walker told Beck, “Do you know, right now, I have something that can bring you into a building that would clean you from covid as you walk through this dry mist? As you walk through the door, it will kill any covid on your body.”

In November and December 2020, Walker unleashed a flurry of #stopthesteal tweets supporting baseless conspiracy theories, saying complicit fraudsters should go to jail, seven states (including Georgia) should toss out the initial election results and vote again, and that Georgia should refuse to certify Biden’s victory.

Personally, Walker seemed indifferent to participating in democracy as a citizen for the majority of his life. He did not vote until the 2020 presidential election, when he was 58 years old. He initially attempted to register in the wrong county, according to Texas state records.

At other times, Walker has demonstrated a profound political incognizance. In a late January appearance on a Daily Caller podcast, Walker was baffled when asked, “Would you have voted for the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill?” which Congress had passed two months earlier amid widespread media scrutiny. “Until I can see all of the facts, you can’t answer the question,” he said. “And I think that’s what is totally unfair to assume someone like myself to say, ‘What are you going to vote for?’”

Such performances have alarmed some Republican leaders, who don’t want to squander the opportunity to take back the seat held by Warnock. Walker “doesn’t have the breadth and depth of knowledge of the issues,” says Marci McCarthy, chair of the DeKalb County Republican Party, emphasizing the need for a qualified individual. “They need to know policy, our top issues in the state.”

In a December interview, Walker showed he clearly didn’t know policy or history when asked about the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. The legislation would restore parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which Lewis, a civil rights icon and congressman — not a senator — from Georgia, helped craft. “You know Senator Lewis was one of the greatest senators there’s ever been and for African Americans was absolutely incredible,” Walker said. “I think, then, to throw his name on a bill for voting rights, I think, is a shame. First of all, when you look at the bill, it doesn’t fit what John Lewis stood for, and I think that is sad for them to do this to him.”

Walker’s flagrant display of ignorance rankled many, including Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter Fund, intended to mobilize and empower Black voters. “There’s no crime in being ignorant,” Albright says, “but there is in not knowing you’re ignorant and going around boasting about what you don’t know. He’s a clear and present danger to our health and democracy.”

In October 1989, the Dallas Cowboys traded Walker to the Minnesota Vikings for five players and seven draft picks, perhaps the most lopsided and worst trade in NFL history. Nearly two years later, Walker had failed to meet the impossible expectations in Minnesota, and his football future looked uncertain. In May 1991 his wife, Cindy, found him unconscious, slumped in his car, the engine running, the garage doors closed. She called 911. After Walker was taken to the hospital, treated and released, he told reporters he had been listening to some music and fell asleep, that he was not suicidal.

Around that time, as he explained to Howard Stern in an interview in 2010, he started playing Russian roulette, seated in the kitchen of his suburban Dallas home, loading a solitary bullet in a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson, spinning the chamber, placing the gun to his temple and pulling the trigger. He did this more than half a dozen times over the next decade, he said, not because he was suicidal but simply for the thrill of competition, a claim that shocked even Stern.

“At no point do you say to yourself, ‘I love living’? ‘I love life’?” Stern asked him.

“No, I don’t think I ever realized that,” Walker said. “I just love to compete. And I thought that was the ultimate game of competition.”

In court documents filed in 2005, however, Cindy claimed that Walker had “made threats to kill himself on numerous occasions.” As Walker’s professional football career ended in 1997, his marriage came undone. He admits in his memoir that he had an affair. And that he became increasingly violent. He had long possessed an angry streak, ever since he was bullied in elementary school as a chubby kid who stuttered. He writes in “Breaking Free” that beneath his deferential demeanor was a “simmering anger” that tempted him to join the Marines instead of playing college football. “I wanted to go into the Marines ’cause I wanted to kill people,” he says in the 2014 ESPN documentary.

Cindy — a runner at UGA, where they met — told a CNN reporter he held a gun to her head a handful of times, that his eyes would get “evil,” which he has not denied. One time in their bed, she said, he threatened her with a straight razor.

Remarkably, Walker opens his memoir with the story of driving across town on Feb. 24, 2001, with the intent to shoot and kill the man who did not deliver on time a car Walker had bought. He wrote that he was “so angry that all I could think was how satisfying it would feel … the visceral enjoyment I’d get from seeing the small entry wound and the spray of brain tissue and blood — like a Fourth of July firework — exploding behind him.”

Spying a “Smile. Jesus loves you” sticker in the window of the delivery truck stopped him, he wrote, and instead prompted him to seek help from a former college track opponent turned counselor, Jerry Mungadze.

Mungadze got to see Walker’s rage up close on at least two occasions. On Sept. 23, 2001, Mungadze called the Irving, Tex., police to protect Cindy, telling them Walker was “volatile” and armed, according to police reports obtained by the Associated Press. He spent a half-hour in their suburban Dallas house trying to calm Walker, who had “talked about having a shoot-out with police.” They did not arrest Walker but placed his house on a “caution list” due to his “violent tendencies” and took away his 9mm Sig Sauer handgun. Another time, at his office, Mungadze had to call the police to intervene when Walker threatened to kill Cindy, Mungadze and himself.

Cindy filed for divorce in December 2001. It was finalized in 2003, but Walker’s threats did not stop. In December 2005, while Walker and his ex-wife were hashing out child custody arrangements in court, Cindy filed for a protective order after Walker made repeated threats to kill her and her boyfriend. The previous summer, after she had declined to attend a July 4 celebration at Walker’s parents’ house, Cindy’s father said Walker told him he was planning to shoot Cindy and her boyfriend. Cindy’s sister Maria Tsettos stated in an affidavit that on Dec. 11, 2005, Walker told her he had a gun and was on his way to meet his ex-wife and her boyfriend to “blow their f—ing heads off.” He later slowly drove by the couple, who were standing outside a mall, and trained his finger on Cindy like a gun. The court issued a temporary protective order and suspended Walker’s license to carry a concealed weapon.

In 2001, when Walker turned to Jerry Mungadze for help, the counselor told him he had dissociative identity disorder, a somewhat controversial diagnosis. In the fifth edition of its Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the American Psychiatric Association describes dissociative identity disorder — formerly multiple personality disorder — as “a disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states” accompanied by an amnesia that often has an individual unable to recall everyday occurrences, personal information or traumatic events. It is often the result of childhood trauma. In his memoir Walker wrote of a dozen personalities, or alters — including the Hero, the Judge, the Enforcer, the Sentry, the Daredevil and the Warrior — he cultivated to cope with the bullying he endured in elementary school.

But others expressed surprise, even doubt about the diagnosis. “I know him better than anybody ’cause I raised him,” his father told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “This is my first knowing about that.”

Of more than two dozen former classmates; high school, college, professional teammates and coaches; high school teachers; journalists and media directors who interacted regularly with Walker; and longtime friends I interviewed for this article — not one said the diagnosis made sense in helping them understand Walker. On the contrary, all said they never saw signs of anything like dissociative identity disorder.

Tom Jordan, the high school coach who was a father figure to Walker, expressed skepticism after reading Walker’s memoir. “I didn’t agree with any of it,” Jordan says. “I think it’s some doctor trying to get rich. I didn’t see any of that in him growing up.”

Usually the disorder is diagnosed by a psychiatrist or psychologist. Mungadze has a doctorate of philosophy in counseling. (He did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.) The diagnosis of a mental illness could also provide a convenient cover for Walker’s past behavior. “It just does not ring true, and nobody has questioned it, but it’s an excellent excuse to use if you’ve pointed a gun at somebody — ‘That wasn’t me; it was somebody else,’ ” says retired Atlanta Journal-Constitution politics editor Jim Galloway.

Walker has tried to reassure voters he’s okay, telling Axios in December he is “better now than 99 percent of the people in America. … Just like I broke my leg: I put the cast on. It healed.”

Details of Walker’s violent past and his outrageous statements already trouble the Republican cognoscenti. Some worry what more could emerge from investigative reporting — or Walker’s own mouth. “The unknowns associated with Herschel Walker, with his history and what his statements in the future may be, make him a foolish risk for Republicans,” says John Watson, former Georgia GOP chair.

At the moment, though, he may be protected by a cocoon of willful ignorance among his supporters. Several people leaving the Dahlonega event had not heard about the accusations that Walker made violent threats toward ex-wife Cindy and others — incidents recently reported by the media. When told about the incidents, they brushed them off. “I’m not the same person I was 20 years ago. We learn from our mistakes,” says Donna Brantley of Dahlonega, carrying an autographed “Run Herschel Run” yard sign. “He’s got the right morals.”