The tents appeared the second week of July. Six of them—red, green, burnt orange—plus a brown one tall enough to stand up in, marked “medical.” They occupied a strip of grass below the trolley tracks, across the street from the Lake Harriet bandshell. The sight startled me. It was one thing to read about encampments in neighborhoods associated with poverty where you might expect to see them. Quite another to encounter the tents in my Linden Hills neighborhood, up the street from our house on Lake Harriet.

They put homelessness—and all it represented—in my face. I could not look away. I must get to know my new neighbors. So I stopped by one morning on my walk with my dog.

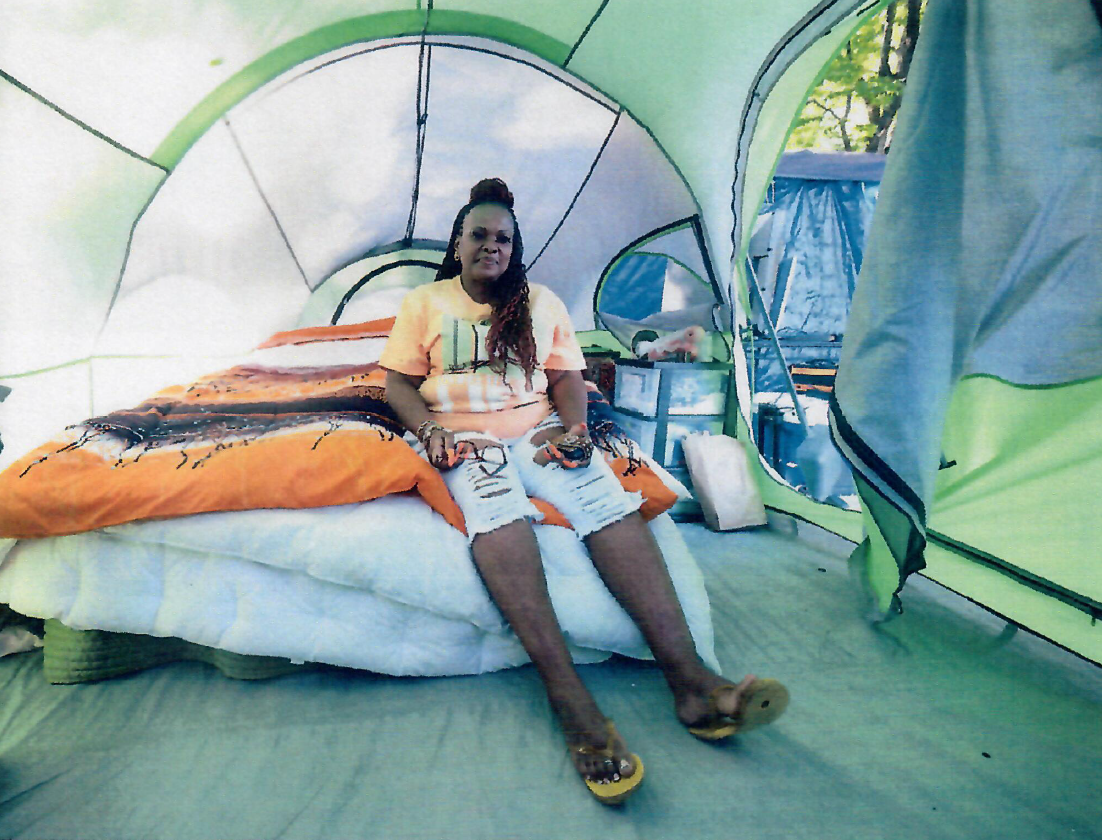

The tents straddled the the water pump. The concrete area served as the encampment’s patio, with a pair of park benches and a large blue tent marked “food” on one side. Michelle Smith, a woman with cornrows down to her waist and pink fingernail extensions, stood talking to two women from the neighborhood about the lack of adequate housing. She turned out to be the camp’s organizer, the first in the city to be granted a permit by the park board. They provided a handwashing station, two beige portable toilets, and a half dozen trash and recycling bins. “I came here to get the wealthy folks’ attention so they’d help us,” Michelle told me.

One of my neighbors, Nathalie, offered to send me a link to the Google drive spreadsheet where she posted Michelle’s requests for the camp.

Though Michelle, 62, stays at the camp, she has a studio apartment in a subsidized building downtown. But she was once homeless. After a second marriage ended in divorce and her money ran out, she ended up in shelters. She applied to the county for assistance but had to wait five years. “God got me out of it,” says Michelle, who wears her Baptist upbringing like a campaign button. “He found me a way to Section 8 housing.”

That was about two years ago. This is her way of giving back, rooted in the volunteer work she’s done with churches over the years. An acquaintance from Freedom from the Streets asked her to help set up the Powderhorn camp. After that, she moved to Lake Harriet. “I really wanted to be a missionary,” she says.

I returned later that afternoon with some cold cuts, ground beef, pasta, marinara sauce, and other items from the list. Michelle, preparing dinner behind a large grill, remembered me by my hair even though I’d been wearing a baseball cap. “Look at those white curls,” she said with her big laugh.

While we chatted, a teenage boy walked by and said to her and some men on the bench, “Have a good night.” She explained he worked at Bread & Pickle across the street and employees had been dropping off food for them. “You, too,” she said to the teenager. “God bless.”

In its most recent study, a survey from a single night in October 2018, the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation counted 11,371 people experiencing homelessness statewide, a 10 percent rise from its previous survey in 2015 and the highest in the study’s 30-year history. More than a third were in Hennepin County. Since they were not able to talk to everyone without a home, Wilder estimated on any given night in 2018 that 19,600 people experienced homelessness in Minnesota with a total of 50,600 for the year. The study also found a significant increase–62 percent over its previous study–of those who were unsheltered–staying under bridges, in public transit stations, riding trains, and so on.

But we’ve never seen anything like this summer. In Minneapolis parks alone, there were people living in an estimated 351 tents among 22 parks as of September 10, with another 49 tents along the Greenway and smaller encampments elsewhere. (St. Paul has seen a tenfold increase in unsheltered homeless people this summer over last, though this article will focus on Minneapolis.) In July, the largest outdoor encampment in the metro area’s history, at Powderhorn Park, had 560 tents with an estimated 800 people.

While the exact number of people experiencing homelessness at the moment is unknown, those once hidden have become visible. The coronavirus has constrained space in shelters and prompted many to pitch tents rather than risk contagion indoors. The Governor’s emergency response shut down spaces that once harbored the homeless, from libraries to trains—where as many as 160 a night sought shelter. The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board’s resolution in June to provide refuge in the parks along with a volunteer movement to supply tents, food, clothing, and other support suddenly made the parks the focal point of a housing crisis long in the making.

We are in the midst of a historic confluence driven by a pandemic and social unrest to systemic injustices have laid bare issues that have long plagued our society and forced a reckoning. We can no longer be satisfied with volunteering once a month to cook a meal for a homeless shelter. The moment demands more.

In the early weeks, every time I stopped or drove by, I saw Michelle out front talking to someone. There’s a bit of Barnum in the way she works her audience. “No drugs, no drama, no violence,” she promised. She kept the area neat and clean. She even asked to borrow my lawn mower since the park crew stopped mowing once the tents went up. She initially described the camp as a place for families and expectant mothers, but I never met one. People came and went, but no families. By the end of September, they were eight: Don, Dre, Sam, Chris, N.O. (short for New Orleans, where he’s from), Joey and wife Anastasia, and, of course, Michelle.

NextDoor lit up with complaints. The posters expressed fears about increased crime. They called out neighbors making donations as enablers. They said the homeless should go to shelters, where there’s plenty of room, thanks to Covid. One woman thought Michelle was playing us, preying upon sympathy and guilt.

But sentiment seemed to run higher in support. A steady stream of people dropped off cash, food and supplies, whether prompted by the “donations” signs posted on trees or Michelle’s Google wish list. The camp grew with folding chairs, card tables, coolers. A France 44 employee delivered bags of ice daily. A couple of televisions appeared along with a stack of DVDs. Someone donated a generator that residents recharged at Bread & Pickle. St. John’s Church, up the hill, donated a shower. Cases of bottled water and Gatorade were stacked inside the food tent. Loads more food and clothing were piled into the storage tent.

Michelle was particular in what she’d take. She wanted double queen air mattresses, “the higher ones because some people have back problems.” She accepted only new blankets and clothing: “I don’t take used because of sanitation.” She turned down homecooked food unless prepared by someone she knew. Yet she was quick to express her gratitude: “These people have been so generous to us.”

One group picked up laundry they washed in their homes. Michelle complained about the last batch. “They did a lousy job folding it, and the hoodies were dingy,” she told one of the volunteers.

Chris, 28, came to the Lake Harriet encampment in early September with everything he owned in a backpack. He told me his story one afternoon. He wore a black flat bill cap set backwards over short dreads, a Marvel Comics T-shirt, cranberry colored jeans, and a pair of black Sport shoes that Michelle secured.

Chris, 28, came to the Lake Harriet encampment in early September with everything he owned in a backpack. He told me his story one afternoon. He wore a black flat bill cap set backwards over short dreads, a Marvel Comics T-shirt, cranberry colored jeans, and a pair of black Sport shoes that Michelle secured.

In January Chris completed treatment for alcoholism and mental health issues in River Falls, Wisconsin. When Covid shut down the college town in March, he lost his assembly line job at Best Maid Cookies. Unable to afford rent, he returned to Minneapolis, where he grew up. After high school—he dropped out before his senior year but got his GED—he had bounced around from his mom’s place to his grandmother’s and the streets. There he snatched brief stretches of sleep in abandoned places or on public transit while managing to stay employed, at one point balancing jobs at Home Depot and McDonald’s.

He receives government assistance—enough to pay the bill on his cell phone—but wants to find a job. First, he needs to replace his identity card and social security card, which he lost in Wisconsin. He’s helped out with whatever small tasks Michelle asks him to do around the camp, but the days become tedious. “It’s the same thing every day,” he says, “just sitting around and building on the stress.”

There’s not a template for someone who ends up homeless, but the Wilder study does identify trends. Sixty-four percent suffer from a serious mental illness. The three most common—major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and manic-depression—have increased significantly over the past two decades. Fifty-seven percent have a chronic physical health condition, such as pain, high blood pressure, asthma, or diabetes. Twenty-four percent have a substance problem involving alcohol and/or other drugs. Half of the respondents, like Chris, have two or more of these conditions. Perhaps surprisingly, the Wilder study found not all are unemployed: three out of ten adults had a job of some sort; 13 percent worked at least 35 hours a week.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as violence, abuse, neglect, loss of a family member to suicide, substance abuse, parental separation, or family members in prison put individuals at higher risk for homelessness. The majority of homeless adults, almost three out of four, had experienced at least one of these. Fifty-nine percent reported multiple ACEs. For each ACE, the average age someone becomes homeless drops. Chris’s father had been in prison; Chris was first homeless in his late teens.

People of color are overrepresented among the homeless population. More than one-third of the adults in the Wilder survey were Black (37 percent), higher than any other race or ethnicity, while only 5 percent of the state’s adult population is Black. Native Americans, who make up 12 percent of the homeless adult population compared to one percent of Minnesota’s total adult population, are 21 times more likely than whites to be homeless.

Beyond these characteristics are often commonalities. Michelle Decker Gerrard, one of the Wilder study’s authors since its debut in 1991, mentions a Black mother she interviewed, heartbroken she could not afford a birthday present for her son. “There’s a tendency to think homelessness only happens to some people,” Decker Gerrard says, “but over the time I’ve been doing these counts and hearing people’s stories, it strikes me every time there’s always one similar to my own.”

James was about my age, mid-50s, with black frame glasses and a good heart. He said he tried to help people best he could, giving them rides in his van to wherever they needed to go. He had owned a house on the other side of the lake, at 47th and Colfax, but a motorcycle accident wrecked his back. He couldn’t work. The medical bills put him under. He lost his house, wound up on the streets and eventually in the Lake Harriet camp. He’d been happy to cut the grass the first time I dropped off my lawn mower, and I sometimes saw him riding his bike around the lake. But then he was gone. Michelle told me he stormed off after getting a parking ticket in the pay lot across the street where he’d left his van overnight.

Another time I dropped off my lawn mower, Jimmy helped me unload it. A short guy with shoulder-length, shiny black hair, he excitedly told me he’d just been approved for subsidized housing. But a day or two after he’d cut the grass, he’d slapped his girlfriend, and Michelle called the police to have him removed. “No violence,” Michelle says. “I can’t tolerate that.”

Don is an early riser. Often on my morning walks, he is the only one I see awake and dressed for the day, smoking a cigarette. About six feet, slender, hair cut short, beard trimmed neat, he’s the one Michelle entrusts with the key to the supply tent when she’s gone. Don, 40, shares the large tent marked “security” with Chris and helps defuse disputes when they arise, a role that belies his mellow temperament.

In September Don and a couple others had to chase off a young man brandishing a short machete, but most days follow the same tedious routine. “I want to find a job,” Don tells me. “Sitting around all day is depressing.” He lost his job at the Bloomington Walmart three months earlier when someone stole his car and he could not get to work. It wasn’t long before he ended up in a tent.

Dre is the camp comedian, punctuating conversation with comments like, “My name is Andre and I approve this message,” and “I don’t make the news, I just report it.”

He got a degree at Dunwoody and later trained as a chef. He tells me proudly that he has made eggs benedict and lobster bisque at the camp, even baked Don a birthday cake in the gas grill. Dre, 54, worked at Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse downtown, making $19.75 an hour, and lived in a one-bedroom apartment in Richfield with two fish tanks and a large flat screen TV. He had saved up six months of living expenses, but when the pandemic shut down Ruth’s Chris, he lost his job.

I run into Dre one afternoon already a couple of drinks in, a clear plastic cup with some lonely ice cubes in hand. He’s in a philosophical mood. “It’s frustrating, but you’ve got to keep a positive attitude,” he says about his current situation. “Got to turn obstacles into opportunities.” The Lake Harriet camp is better than others where he’s stayed, but not where he wants to be. “Nobody grows up saying, ‘I want to live in a goddamn camp,’” he growls.

It's hard to...learn what's needed to live in an apartment or house. It can be overwhelming. If you provide space and wraparound services, they will get the help they need. John Cole, Director of Align Minneapolis

There are many routes to homelessness: job loss, divorce, a medical catastrophe, work hours reduced, eviction or foreclosure, losing child care. “Usually it’s not just one crisis but one plus another—the pile-on effect,” Decker Gerrard says.

This year has contributed additional factors. The uprising displaced some people when their homes or neighborhoods were destroyed. People staying with friends or extended family were asked to leave when crowded housing no longer seemed safe.

The common denominator? Lack of affordable housing.

According to the University of Minnesota’s Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, more than one in four of Minneapolis’ households earns less than 30 percent of the area’s median income ($28,300 for a family of four), which is the benchmark for those eligible for public assistance. “A huge concern in Hennepin County is the gap between the cost of housing and incomes is very large,” says David Hewitt, director of Hennepin County Office to End Homelessness. “We estimate around 74,000 households are below the AMI, but we have only 14,000 units of housing they can afford, so there’s a 60,000 gap.”

A collaboration funded by the city, county, state, and Minneapolis Public Housing Authority will open approximately 110 new units of affordable housing through February 2021. An additional 290 have closed on financing and will begin development in the coming year. Those 400 units, though, are a long, long ways from the 60,000 needed.

One afternoon Joey tells me the story of a camp intruder. He fills a plastic gallon jug with water from the hose behind the water pump and talks while walking back to his tents, where he pours the water into a large bladder attached to a tree. His wife Anastasia, who has short brown hair, transfers a plastic tub of soapy dishes—plates, cups, a French press—from atop a green wooden wagon to under the tree and rinses them with a hose suspended from the bladder. When she’s done, they will cook their dinner on a Coleman stove, like they do most nights.

They have two tents, one for sleeping, one for lounging. Joey woke at 5:30 on a Sunday morning when a shadow from the lounge tent crossed his face. Realizing the intruder had taken Anastasia’s backpack, he gave chase on his bike and caught up with the thief by Bde Maka Ska. Joey—who is built like a fireplug and has a convincing temper—pulled a knife. The thief dropped the backpack and fled. Joey found a small bag inside that did not belong to his wife but had, among other items, a check stub with a Linden Hills Boulevard address. He rang the bell at the house and returned the items to a surprised couple roused from their sleep. “I wanted to do the next right thing,” he says.

Joey, 38, had been working in Denver, paid cash for removing asbestos. That work dried up with the arrival of the coronavirus. He and Anastasia, 40, hitchhiked around Nevada and California until a government check came through. They rented a car and drove to Minneapolis, where his mother lives. “We’re self-sufficient,” he says. “I can’t stay with my mom.”

They kicked around several of the encampments, before stumbling upon Lake Harriet. Michelle let them stay. He’s been doing odd jobs when he can find them—fixing gutters, laying carpet, a demolition job for a neighbor—but when the weather turns cold he wants to head south. “I’d like to buy a small trailer,” he says. “Maybe my sister will let me hitch it to her truck.”

The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board (MPRB) has faced its own reckoning in the wake of the pandemic and uprising. As Lake Street burned in late May, a loosely organized group of mostly white activists calling itself the Sanctuary Movement arranged shelter for the homeless at the Sheraton hotel on Chicago. But within two weeks, the situation had disintegrated into a disaster with the hotel overrun with rampant drug use (many overdosed; one person died) and sex trafficking. When the owner did not receive payment, he deactivated the access cards; people with belongings locked in rooms busted doors and windows. County outreach workers found indoor shelter for many who had been staying there. Members of the Sanctuary Movement abandoned the hotel and led some folks to Powderhorn Park, where they pitched ten tents. Superintendent Al Bangoura, fearing the same problems would inhabit the park, called for their removal, but the Governor’s office intervened, claiming Walz’s executive order prohibited disbanding the encampment.

As Powderhorn swelled and inspired smaller encampments across other parks, Bangoura and the nine park board commissioners found themselves in a tough spot. Their mission is to provide space for recreation and preserve the land, not shelter the homeless. No one on the board had training in housing and support services. They scrambled to find partners with knowledge and resources to deal with the health and safety challenges. On June 17, when the MPRB declared the parks a refuge for people experiencing homelessness, it did so with misgivings. “Everyone [on the board] is in agreement,” MPRB president Jono Cowgill told me, “that people that are unhoused deserve housing and that living in a park is not a dignified housing space.”

The Sanctuary Movement, a loosely organized but headstrong campaign, complicated matters. They coordinated volunteers to serve food, pick up trash and provide supplies like toiletries, clothing, and tents. Some commissioners, most notably Londell French, stood with it. Others believed members of the Movement, though well-intentioned, were doing more harm than good. Commissioner LaTrisha Vetaw branded the movement—and like-minded, well-meaning liberals—“white saviors.”

“They tried to make like it was some type of Utopia, but nothing about living in the park says ‘sanctuary,’ to me,” says Vetaw, who spent time in Powderhorn, where she got propositioned for sex and saw a dirty baby swarmed by bees while his father talked on a cellphone. “If you tell them it’s okay and safe, you have to own this when something happens to them.”

And things did happen. Robberies, rapes, sex trafficking, assaults, drug overdoses, shootings. The incidents in Powderhorn grabbed most of the headlines, but they happened elsewhere, too. Yet some white saviors continued to insist upon self-sufficiency and resist outside interference. Commissioner Meg Forney cried when she recounted to me how they refused to identify the man who raped a 14-year-old girl in Powderhorn and neglected to call paramedics when a woman overdosed in Peavey Park. “She’s lying in the hospital, and she’s brain dead,” Forney says. “These communities need to realize these people need specific services to help them.”

The county sent outreach workers into the encampments to help residents find safe housing and medical assistance. But the Sanctuary Movement, eyeing the establishment as part of the problem, refused to cooperate. “There’s enough work for us to address the real problem of homelessness in Minnesota,” one exasperated outreach worker told me. “When we have people creating problems, that makes it impossible for us to do our job and we have fewer people getting served.”

The lines blurred between the Sanctuary Movement and rogue activists who seemed intent on exploiting the circumstances. They seized upon the encampments as the embodiment of social and racial injustice. One outreach worker who had spent endless hours in the camps recounted he had heard reports of families who didn’t feel safe, threatened by activists if they left. And others paid by activists to stay. “These people are using the homeless folks as pawns to bring bigger notice to these problems we have,” he says. “They say they’re working for these people, but they’re actually working against them.”

On July 15, citing health and safety concerns, the MPRB unanimously approved a resolution to reduce the number of parks that would accommodate encampments to 20 and limit the number of tents. Powderhorn, Elliot, Kenwood, Matthews, and Loring were cleared as a result. By late September, encampments with permits remained in 15 parks.

One of the early encampments established itself outside Theodore Wirth Home, the superintendent’s residence in Lyndale Farmstead Park. The camp has provoked Bangoura’s own personal reckoning. “It’s been hard,” he admits. “I recognize that people are struggling and suffering. It reminds me of the work I have to do every day and be committed to helping find shelter.”

On September 5, a group marched from Bryant Park to his house. From inside, he could hear his name in their speeches calling for solutions. Then his 15-year-old son, who was practicing his viola, called out, “Dad, a guy is climbing the house.” A man had scrambled onto the porch roof and spray-painted the security cameras. “I support peaceful protest, but when they crossed the line, I called 911,” Bangoura says. “I was concerned for my family’s safety.”

At best, the encampments were a stopgap. The MPRB does not see them as safe or humane once the weather turns cold, so the impending winter amplifies the urgency to find appropriate accommodation. “This is a crisis and we need help getting people into shelter and housing,” Bangoura said in late September. “What is the solution going to be in the next month?”

Shelters save lives. So goes the platitude, but we don’t have enough of them. In the 2018 Wilder survey, nearly one in three people (32 percent) said they had been turned away from a shelter in the past three months because it was full–which factored into the 62 percent jump in unsheltered homeless. Last year, the city, county, state and community partners committed to three new shelters with a combined additional 250 beds to serve specifically women, American Indians and the medically fragile. The latter two are expected to open this winter, but the 30-bed women’s shelter is on hold after neighbors to the proposed site in Gordon Center blocked it.

This winter may endanger more lives with the governor’s eviction moratorium due to expire at the end of the year at the same time as federal rental assistance from the CARES Act. “There’s obviously a great bit of concern about what will happen then,” Hewitt says.

The consensus for an enduring solution is supportive housing, meaning shelter and continuing social services, affordable and accessible to all. “Supportive housing has been a proven best practice in ending homelessness regardless of circumstances,” says Cathy ten Broeke, state director to prevent and end homelessness and director of the Minnesota Interagency Council on Homelessness.

The support is critical. Most people who have wound up homeless need assistance addressing the issues that landed them there, whether it be job training or mental health counseling. “People on the street learn a whole set of survival skills,” says John Cole, director of Align Minneapolis, an interfaith coalition of 17 congregations addressing homelessness. “It’s hard to unlearn those and learn what’s needed to live in an apartment or house. It can be overwhelming. If you provide space and wraparound services, they will get the help they need.”

Once someone loses their home, a variety of barriers make it hard to get back into housing. More than half of adults experiencing homelessness in Minnesota are on a waiting list for subsidized housing, with the average wait running over a year. Once they’re approved, there’s no guarantee they’ll find a place to live. With vacancy rates around 1-2 percent, landlords often deny housing because of credit problems, lack of references, past evictions, previous arrests, and issues of mental health or substance abuse—in spite of protective ordinances or Section 8 regulations.

Prejudice also factors into landlords turning away applicants. Every advocate or official I asked about this–at least a dozen–had heard stories to this effect. “It’s hard to prove there is a racial component to it, but we know sometimes there is,” says Don Ryan, program manager at Hennepin County and liaison to the encampments.

It’s yet another symptom of the systemic racism that has exacerbated the crisis. “Implicit bias conspires against people of color being able to have equal access to work and wages and they are denied available places to live because of their color,” Cole says. “Whatever injustices someone already encounters as a person of color are magnified when you’re homeless.”

The Wilder study concluded the need to address homelessness at its racist origins. I asked Vetaw how I and other white people can dismantle systemic racism. “Start with your family,” she says. “It’s not just systemic in our workplaces but in the way we’re thinking. Talk about what you’ve been witness to and participated in. Break down some of that systemic thinking and take action.”

One day in early September, Mike Reier looked up from his lunch at Bread & Pickle. Losers, he thought. Why in the hell is the city allowing people to put up tents in parks?

A middle-aged white guy who’s had a successful career as an entrepreneur with several tech and healthcare companies, including Benovate, and lives in Minnetrista, he thought, These people have done this to themselves and need to get their act together. “It’s a horrendous way of thinking, but I’m being honest,” he admits. “Those of us out in the suburbs don’t have a clue. We have these preconceived ideas without any idea what the critical challenges are.”

He might have persisted with this mindset if his friend had not commented, “They have nowhere else to go.”

That prompted Reier to cross the street, where he met Michelle. She told him her hope to find a building where she and the others at the encampment could live. So began the education of Mike Reier.

He started talking to people at more than a dozen nonprofits addressing homelessness. He came to understand the multiple forces at work that land someone in a tent and came to believe in the need for more supportive housing. He embraced Michelle’s vision for a place with “program concierge services” that she would coordinate and threw himself into the cause for “Project Back to Home.” He assembled an advisory board; put up a website (projectbacktohome.org); and raised money. Following Michelle’s path to “crawl, walk, run,” the goal of the first phase is to raise $90,000 that will provide immediate housing for 12-18 people through the winter. The next phase requires $500,000 to purchase and renovate a building. The third phase calls to expand housing and services for a growing number. He has forged partnerships with St. Stephen’s to offer job training, American Indian Community Development Corporation to assist with property acquisition and the Constellation Fund to contribute funding. “I know I sound crazy because I think this is possible, but I’ve done this before,” Reier says, referencing his startup companies.”This is no longer a government problem, no longer a nonprofit problem. We’ve all got to jump into this.”

© John Rosengren