The first time I heard about Stan Rother, I was standing in the room where he was killed. It was a sitting room, about 28 feet by 20 feet, in the rectory of Santiago Apóstol, the church in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, where the American priest had served as a missionary. He had been using it as a hideaway bedroom since his name appeared on a death list. Apparently his acts of charity to the impoverished Mayas in his parish had angered the military government.

The priest telling me this story 15 years after Rother’s 1981 murder was his friend, Father Greg Schaffer, a missionary in the neighboring parish. Schaffer explained how three masked men had found Rother there one night that July. The 46-year-old Rother, strengthened by years of working with his hands, must have fought them, Schaffer said, because his knuckles were raw. From his words, I could imagine the struggle that had taken place, how Rother’s faith had played out, the assassins finally pinning him into a corner, shooting him in the jaw. I could see him crumple. See one of the men bend over, level his Smith & Wesson handgun against Rother’s left temple, and fire. See the men flee while Rother’s life leaked out of him.

I marveled at the blood left splattered on the wooden walls and knelt to place my finger in the hole the final bullet had punched in the tile floor.

Rother’s fidelity to his parishioners and his willingness to die for his faith elevated him to the status of a saint in Santiago Atitlán. The Church may soon concur. A Vatican investigation determined in July 2015 that Rother had been killed in odium fidei, in hatred of the faith, making him a martyr. The following year, in December, Pope Francis approved his beatification, the last step before sainthood, making Rother the first priest born in the United States, the first missionary sent from the U.S., and the first American-born male to be so revered. If canonized, he would join Elizabeth Ann Seton and Katharine Drexel as the only Roman Catholic saints born in the U.S., and would be the first male among them.

Stan Rother is an unlikely hero. He was born on March 27, 1935, in Okarche, Oklahoma, to parents from a long line of German Catholic farmers. He grew up during the Depression in a home without running water. He milked cows before school, drove a tractor by age 10, played catcher for the Holy Trinity High School baseball team and knelt with his family around the kitchen table to pray the rosary. At Assumption Seminary in San Antonio, Texas, he laid sewer pipes, repaired laundry equipment and tended the grounds, but flunked out because he could not keep pace with his courses in Latin. His bishop gave him another chance at Mount St. Mary’s, a seminary in Maryland, where he sought tutoring in Latin and graduated. He was ordained in 1963. Yet he doubted his pastoral worthiness.

Rother bounced around several parish assignments in Oklahoma City and Tulsa before accepting an invitation to join the diocesan mission in Santiago Atitlán, a highland village of 20,000 inhabitants, most of them Tzutujil Indians. Arriving in 1968, the handyman priest made a weak first impression among the other, more academic missionaries. He felt out of place during their political and theological debates but threw himself into the construction of a hospital. He also applied himself to learning Tzutujil [pronounced ZOO-too-heel], a complex Mayan dialect spoken by most of his parishioners. Many of the other missionaries could not speak it. It took Rother three years to learn how to preach in the language.

By 1975, all of the other priests had either left Santiago Atitlán or died, leaving Rother as head missionary. His commitment and faith had intensified with his immersion into the lives of those he served. “He had sensitivity to the poorest,” said Sister Ana Maria Chavajay, one of nine Carmelite nuns who had come to live in Santiago Atitlán during the final year of Rother’s life. “He identified with them as one of them. The people would catch that from him. He would sit down with some of the older people and eat with them.”

Chavajay and the other sisters teased Rother about the shabby state of his clothes, which had patches sewn upon patches. When an American benefactor sent him money to refresh his wardrobe, he showed the letter to Chavajay and laughed. “I don’t need new clothes,” he told her. “The ones who need it are the poor people. Put that money in the account to help them.”

Less than a week later, Schaffer intercepted Rother on his way home through San Lucas Tolimán. ‘You can’t go there,’ Schaffer warned him. ‘They’re on the streets to get you.’

And so he lived by one of his favorite scripture passages, Matthew 25:40, “Amen, I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.”

Rother continued to improve his Tzutujil and commissioned the translation of the New Testament into his parishioners’ native tongue. He welcomed their Mayan rituals — which some priests had condemned as heretical — into the liturgy. He accepted invitations to eat in their homes, which often meant sitting on a dirt floor. They called him Padre Aplas, their name for Francis, Rother’s middle name. The town elders presented him with a symbolic scarf and anointed him an honorary elder. He wore the scarf and the title with humble pride.

By the mid-’70s, Guatemala’s 36-year civil war, which would claim the lives of an estimated 200,000 people before it ended in 1996, had intensified and spread into the countryside. Guerillas moved through the mountains outside Santiago Atitlán with the sympathy — and sometimes support — of the Atitecos, the townspeople. The majority of Guatemalans lived below the poverty line, and the military government used violence to suppress the poor, who were upset over low wages, the concentration of wealth among a small minority and the inequitable distribution of land. The army targeted the Church, which it deemed to be on the side of the oppressed. Rother reported back to Archbishop Charles Salatka of Oklahoma City in September 1980, telling him how soldiers in one town had lined up some 60 men associated with the Church and shot every fourth one.

Guatemala’s president, Fernando Romeo Lucas García, had reportedly said he would rid the country of missionaries — whom he believed were preaching communism — within two years. Death squads had killed four priests that spring and summer. Many other priests had fled. “The reality is that we are in danger,” Rother told Salatka. “They have not killed an American priest yet.”

The missionary and his assistant, Father Pedro Bocel, a full-blooded Kaqchikel Indian, stayed off the streets after dark. They locked the doors and gates. Rother erected cyclone fencing around the rectory and convent and fitted the windows with bars. After someone threw grenades into a convent and rectory in the eastern part of the country, he abandoned the bedroom he had slept in for 12 years for one fortified with walls made of stone instead of wood. “If I get a direct threat or am told to leave then I will go,” he wrote to the archbishop. “But if it is my destiny that I should give my life here, then so be it. . . . I don’t want to desert these people. . . . There is still a lot of good that can be done under the circumstances.”

A month later, the danger intensified when military trucks loaded with soldiers rumbled into Santiago Atitlán and the army set up camp on its outskirts. They occupied part of the parish farm, land Rother had spent long days clearing with a bulldozer. Men from town started to disappear. One of them, an ex-seminarian who had married, was shot in his home by masked men, dragged to a waiting car, and driven off while his pregnant wife watched helplessly, holding their daughter in her arms.

Terror gripped the village. Some Atitecos left to hide elsewhere. Hundreds more sheltered at night in the 16th-century stone church. Rother slept with his shoes on in case he had to confront intruders. Several catechists took turns keeping watch through the night. The priest admitted his fear, but told Salatka in a November letter, “I have no intention of leaving here yet. . . . I still don’t want to abandon my flock when the wolves are making random attacks.”

He explained to his friend Frankie Williams, a woman from Wichita, Kansas, who had visited and supported the mission, that “at first signs of danger, the shepherd can’t run and leave the sheep fend for themselves. I heard about a couple groups of nuns in Nicaragua that left during the fighting and later wanted to go back. The people asked them where were you when we needed you? They couldn’t stay and were forced to leave. I don’t want that to happen to me. I have too much of my life invested here to run.”

By December, 10 men had disappeared from the village, including a friend of Rother’s who left behind a wife and three children. The town now had seven widows and 30 fatherless children since the soldiers had arrived. Rother tried to stay neutral in his homilies and conversations, but found it increasingly difficult.

One of the parish’s brightest catechists was Diego Quic, a 29-year-old man with a wife and two young sons. Quic wound up on a death list after openly criticizing the army. He sought refuge in the rectory, which put Rother in a tough spot, torn between his desire to help and his fear of endangering his own life by providing sanctuary to a government enemy. He knew that even simple acts of charity were construed as sympathizing with the rebels. “Shaking hands with an Indian has become a political act,” he wrote. In the end, his pastoral orientation trumped prudence, and he gave Quic a key to the rectory.

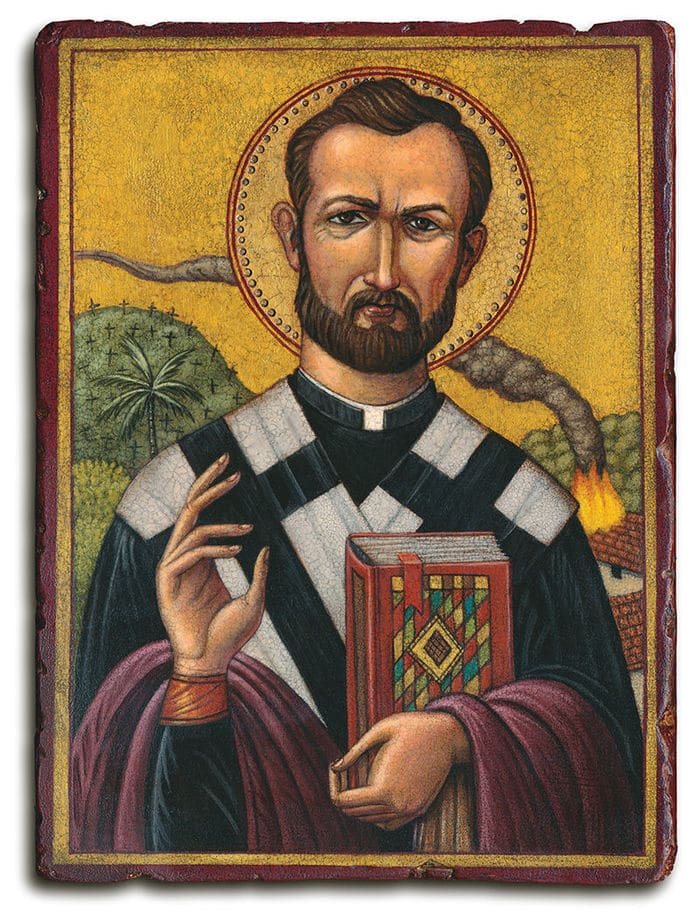

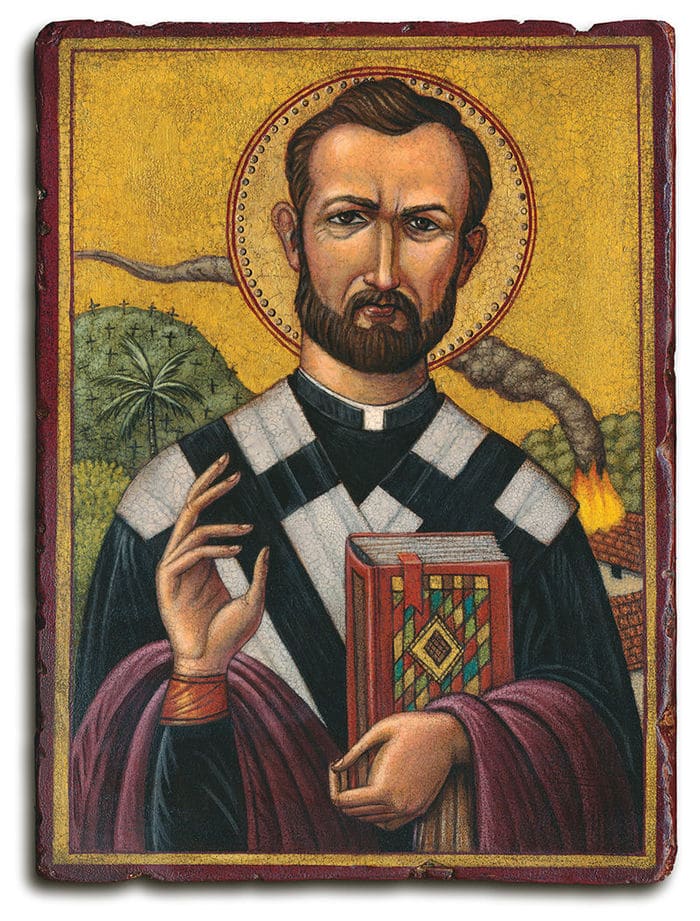

Illustration by Marc Burckhardt

On Saturday evening, January 3, 1981, Rother relaxed in the rectory’s living room, smoking his pipe and listening to an opera with Father Bocel and Frankie Williams, who was visiting for the holidays. Hearing a commotion outside, they stepped onto the porch. Four masked men had ambushed Quic in the plaza. He had run to the rectory porch and clung to the wooden banister. The thugs pried him loose and dragged him to a car, his head cracking against the concrete steps. “Padre Aplas,” he screamed. “Help me!” But Rother, paralyzed with fear, could only watch in horror as the men stuffed Quic into the car, its tires spitting dust as it exited the plaza.

Four days later, the soldiers camped on the parish farm claimed to have spotted guerillas in the area and in retaliation gunned down 17 people at a nearby coffee plantation. The bloody corpses were laid in the plaza. Under the watchful eyes of both his Tzutujil parishioners and the occupying army, Rother walked among them, tears wetting his cheeks. He ordered the seven bodies of the slain Catholics to be carried into the church for Christian burial. “He cried a lot,” Sister Chavajay said. “It was the first time I’d seen him cry.”

That Friday, at the monthly diocesan meeting with the bishop across the lake in Panajachel, Rother’s ears rang with Quic’s cry for help. His eyes smarted from the sight of his murdered parishioners. He stood and made an emotional appeal to his fellow religious: “What are we going to do?”

A thundering silence filled the room. These men and women were missionaries, not mercenaries. They had come to build schools, to teach mothers about nutrition, to administer the sacraments, not to insert themselves into a civil war. Father Greg Schaffer, who was there, knew it would be suicide to do so. Sister Linda Wanner, a School Sister of Notre Dame working with Schaffer in San Lucas Tolimán, recalled, “We were all caught up in this helpless, impossible feeling — what can we do? This is so much bigger than all of us.”

But after what Rother had experienced that week, he wanted to do something.

Sister Cecilia, an elderly Maryknoll missionary who was like a grandmother to them all, offered, “We can take up a collection for the widows of the families.”

Rother turned to her and snapped, “We don’t need the money.”

“He wanted the church to take a stand, to speak out,” Wanner said. “But everybody was spooked, not knowing what death or repression would come next.”

Rother sat down.

Less than a week later, Schaffer intercepted Rother on his way home through San Lucas Tolimán. “You can’t go there,” Schaffer warned him. “They’re on the streets to get you.”

Eventually he received word that his name had been taken off the death list. He didn’t know that the government source no longer had reliable intelligence.

The direct threat Rother had long feared finally materialized. Another priest had word from a government source that he was on a death list. Schaffer told him he had to get out of the country.

Rother refused to leave without Father Bocel, whom he thought was in even more danger as an Indian. Schaffer smuggled Bocel out of Santiago. Rother and Bocel hid in Guatemala City for 16 days until Rother could secure special clearance for his assistant to enter the U.S. They arrived in Oklahoma City on January 29.

And waited. Rother helped out on the family farm and visited friends, but was restless and distracted. He longed to be with his parishioners during Lent. But danger lurked. An Oklahoma physician returned from the Santiago Atitlán mission and advised him it was still not safe. Family members sometimes found him seated alone in a darkened room, brooding.

Eventually he received word that his name had been taken off the death list. He didn’t know that his government source no longer had reliable intelligence.

Bocel went back to Guatemala in March, though not to stay in Santiago. Rother sought his archbishop’s blessing to return. Salatka warned him that he might not have the chance to escape again. Rother understood but believed his place was with his people. He could not be the one who deserted his flock. After 10 weeks away, he flew back to Guatemala City.

The CIA station chief there, who liked Rother and cared about him, cautioned him not to go back to Santiago. The local bishop also said it was too dangerous to return to his parish. To both, Rother said, “I must return. I’m their pastor; they’re my people.” He arrived in Santiago Atitlán on the day before Palm Sunday, in time for Holy Week.

Another priest was killed in May 1981, the sixth murdered in 13 months. More had fled. The total number of priests in Guatemala had plummeted from 600 in 1979 (80 percent of whom were foreign missionaries) to about 300. Parish catechists feared offering classes to prepare first communicants and engaged couples for the sacraments. Rother told them they must in preparation for the annual fiesta, and so the parish nearly resumed a sense of normalcy.

The fiesta honoring Saint James, the town’s patron saint, was the social and liturgical highlight of the year in Santiago Atitlán. At Mass on the morning of July 25, St. James’s feast day, Rother blessed a record 101 marriages and administered the Eucharist to 260 first communicants amidst traditional Mayan pageantry. Afterward, Sister Wanner stopped by with three friends. Wanner and Rother knew each other by sight but had not talked much. She told him she would like to get to know him better. He graciously invited the group in, fed them lunch and talked with them for several hours in the sitting room that doubled as his bedroom.

Two days later, Rother went to bed planning to donate blood the next day for one of the disappeared men who had returned and was having surgery to remove a bullet lodged in his hip. Instead, a little after midnight, his assassins entered the rectory.

The second time I stood in that room, in July 2004, I was there to research Rother’s biography. His story had stuck with me, and I wanted to learn more. I talked at length with Schaffer, Wanner, Bocel and many others. The room had been converted into a chapel that people from all over the world visited to pay their respects and to reflect on Rother’s legacy.

Wanner had returned to the rectory on the morning of July 28. Two of the Carmelite sisters had taken the first bus out to tell Schaffer that Rother had been killed. Rother’s body had been taken to the morgue at the hospital he had helped build, but his blood remained on the sitting room floor, pooled in a corner. A diocesan official suggested they save it to remember him. Wanner knelt and reverently scooped the blood into a Mason jar, struck by the thought this was the priest’s essence. “I understood what the blood of martyrs really means,” she said.

The jar containing Rother’s blood was placed on the altar for his funeral Mass. During the consecration, it assumed deeper meaning when the celebrant repeated the words, “This is my body, which will be given up for you. . . . This is the cup of my blood. . . . It will be shed for you and for all men so that sins may be forgiven. Do this in memory of me.”

Rother’s parents wanted to bury him in Okarche. The Atitecos did not want to part with their beloved Padre Aplas. They reached a compromise that sent his body home to Oklahoma and kept his heart in Santiago. The faithful placed his heart in a wooden box, along with the Mason jar of his blood and several personal items, and buried it in the church floor behind the altar.

Wanner visited Santiago in 1991 for a special ceremony to mark the 10th anniversary of Rother’s death. The wooden box was dug up, and its contents were transferred to a metal box to be placed near the church entrance. As the procession passed with candles and incense, Wanner and the others were surprised to see the blood she had collected in the Mason jar had turned brown but not congealed. “There was a hush, and then murmurs of milagro, milagro” — a miracle — she said.

Father Tom McSherry, who had succeeded Rother, officiated the ceremony. He was a motorcycle-riding, long-haired Oklahoman, not given to sentimentality or superstition. “I felt in the presence of something I couldn’t explain,” he told me. He laughed, folded his arms, didn’t say anything more.

To the people of Santiago Atitlán, Rother instantly became a saint. They named their babies after him. They prayed to him. They credited him with miracles.

The Vatican has moved more deliberately, doing due diligence to determine that Rother had died for his faith (making him a martyr) and that he must certainly be in heaven (clearing the way for beatification). He is now one confirmed miracle away from sainthood. Dozens have been reported to the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City, which is leading the campaign for his canonization, but officials are still investigating before passing them along to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints for final consideration. In the meantime, the archdiocese — which withdrew its mission from Guatemala years ago — is raising funds for a $40 million shrine to Rother in Oklahoma City that will include a 2,000-seat church and classrooms — and Rother’s remains. It will bear witness to the enduring admiration for their native son’s commitment to his faith.

Thirty-eight years after Rother’s death, his namesakes in Guatemala have grown up and have children of their own, but his memory remains fresh. On September 23, 2017, the day Rother was beatified in Oklahoma City, a dozen priests concelebrated a two-hour long Mass in Santiago Atitlán with Archbishop Nicolas Thévenin, the Vatican’s apostolic nuncio to Guatemala. The congregation overflowed the church where Rother had served. Afterwards, the archbishop carried Rother’s heart and the Mason jar out of the church and through the streets. A brass band accompanied the procession, reviving the spirit of joy and gratitude the faithful feel for the way their Padre Aplas stood with them.

For me, it’s Rother’s humanity that makes him so endearing. His initial failure to learn Latin in the seminary and his early stumblings with pastoral duties remind me of my own struggles. He was flawed, at times taciturn and temperamental. He was an ordinary farm kid who discovered his place serving the poor. In a time of crisis, he found the extraordinary grace to conform to his faith, even though it cost him his life. All of this makes him seem more like one of us than like your standard saint.

Even if Rother is not canonized, his life, death and faith will still inspire me and countless others. At the Mass to celebrate his beatification, Cardinal Angelo Amato, then the prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, proclaimed, “His blood, united to that precious blood of Jesus, purifies and redeems even his enemies, who are loved and also forgiven. . . . His martyrdom, if it fills us with sadness, also gives us the joy of admiring the kindness, generosity and courage of a great man of faith. . . . This is the invitation that Blessed Stanley Francis Rother extends to us today: to be like him as witnesses and missionaries of the Gospel.”

© John Rosengren