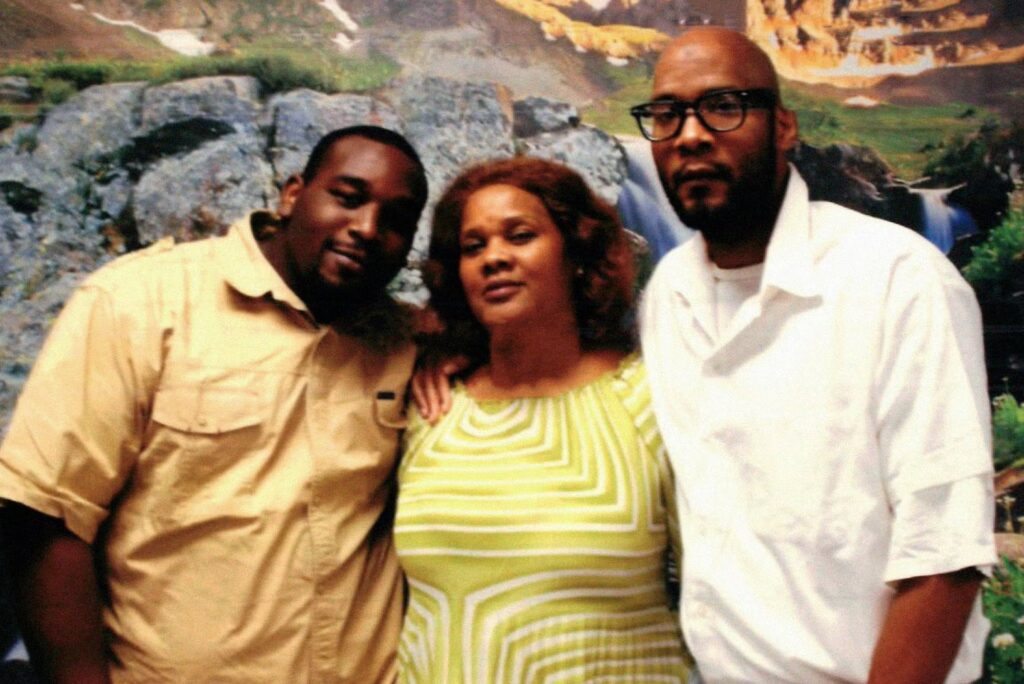

The cell at Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center, where Missouri executes those the state finds guilty of capital offenses, had a phone. They’d brought Marcellus Williams there September 23, the day before he was scheduled to die. His son called that afternoon. Marcellus Jr., thirty-four, has a son of his own, a three-year-old who is on the autism spectrum. “Maybe you can get some proceeds from me getting executed,” Williams told Marcellus Jr., “and you can use them to put your son in a better school, work on his therapy.”

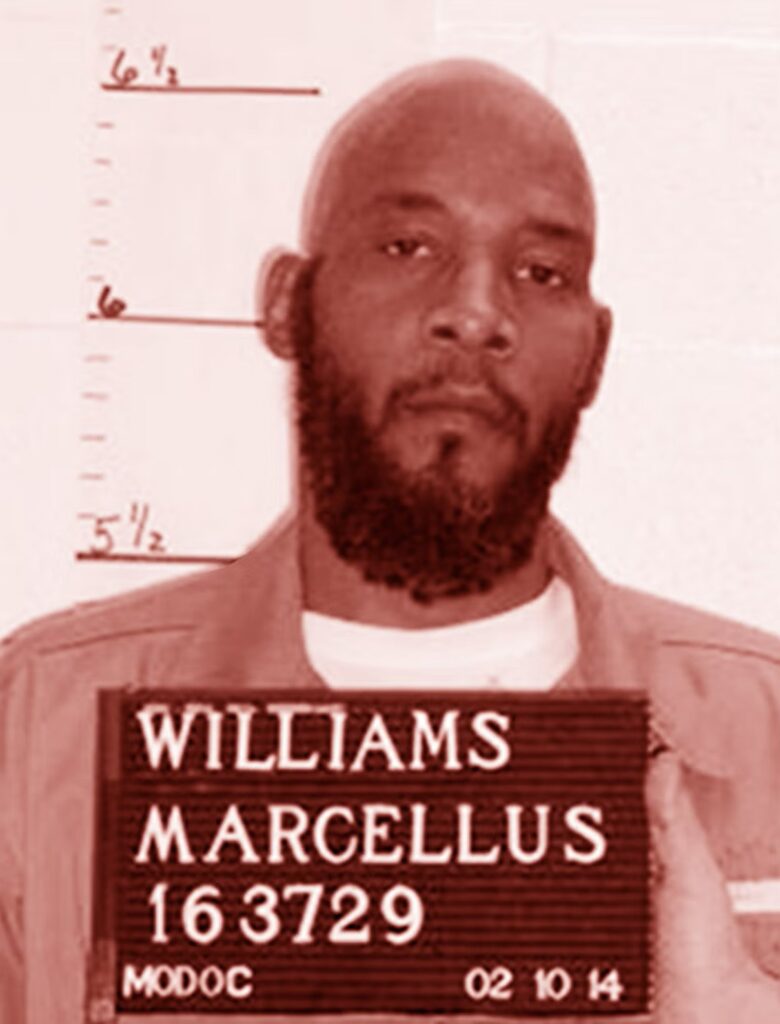

That’s the way he was, say those closest to him. The fifty-four-year-old devout Muslim with a shaved head and salt-and-pepper beard was always thinking of others, wanting what was best for them—even after he was gone. But he wasn’t gone. Yet. There was still a chance. He’d petitioned the state supreme court. The U. S. Supreme Court. The governor. He might get one more reprieve.

Williams and Marcellus Jr. had played this scene before. Back on August 22, 2017. That day, Williams had eaten his last meal. Said goodbye to his son. Prepared himself to die. Then, at the last minute, another governor had halted the process so the courts could consider new DNA evidence. The lawyers had hashed all that out over the past seven years, and now it had come to this: Williams was once again slated to die, a Black man convicted of killing a white woman he insists he never met and did not murder.

“It’s not just about me and my dad,” Marcellus Jr. later told me in a Zoom call from his home in St. Louis. He wore a white T-shirt with a black-and-white silk-screened image of his father’s face below the words in red death ≠ justice. “Because we’re not the only two Black men living this saga. Everybody is at risk of this kind of treatment. It could be somebody’s son, somebody’s brother, somebody’s friend, somebody’s husband going through this same exact thing.”

Indeed, the story of Marcellus Williams underscores the racial injustice in our legal system, and so much more. What happened to him over the quarter of a century since he was charged with the murder of Felicia Gayle—who was found stabbed to death in her suburban St. Louis home on August 11, 1998—reveals grave flaws in the nation’s criminal-justice system. A system rife with systemic racism. A system that sometimes values finality over truth and results over justice. A system prone to wrongful convictions that’s still willing to put a man to death despite real doubts about his guilt, the Innocence Project championing his cause, the prosecutor asking the courts to reconsider, jurors expressing misgivings, and the victim’s family saying, “Don’t.”

The way that Williams’s story played out in his final days captured the attention of politicians in Washington and the national media, sparking renewed debate about the death penalty. His execution raises troubling questions about the process and the results. Was the state justified in its actions? Or did Williams die an innocent man? And, if so, who got away with murder?

The official version of the murder of Felicia Gayle—worked out by the police, developed by the prosecutor, and upheld by the courts—goes like this:

On the morning of August 11, 1998, a twenty-nine-year-old Marcellus Williams drove his Buick LeSabre to a bus stop and hopped a ride to University City, a first-ring St. Louis suburb. He walked to the gated Ames Place—an idyllic neighborhood of two-story brick houses neatly aligned on a grid of leafy streets closed to cars but open to pedestrians—and cased houses to rob. He found one at 6946 Kingsbury with a tree partially obscuring the front entrance from the street. When no one responded to his rap on the front door, prosecutors said, he figured the house was empty. He punched out a window pane near the handle, reached in, and unlocked the door.

Once inside on the second floor, he heard water running. Felicia Gayle was taking a shower after her daily two-mile run. Lisha—as friends called her—lived there with her husband, Dan Picus, a radiologist at nearby Barnes-Jewish Hospital. They’d grown up together in Rockford, Illinois, dated as teenagers (neither one ever seriously dating anyone else), married in 1979, and moved to St. Louis two years later for Picus to do his residency at Barnes. Gayle worked as a crime and general-news reporter at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for eleven years, until she got burned out and left in 1992 to devote herself to volunteer causes and to write a book about her husband’s family history. The couple never had children of their own, though Lisha had grown close to Ebony, a thirteen-year-old girl she had mentored since kindergarten and was planning to take swimming later that day.

The running water stopped. Suddenly aware he wasn’t alone in the house, Williams crept back downstairs, where his feet creaked on the hardwood floor. The prosecutors painted the picture of what happened next: A woman’s voice called out, “Is there anybody here?” Williams slid a butcher knife from a drawer in the kitchen and waited by the base of the stairs. Lisha came down the steps: “Who is that?”

That’s when they say Williams pounced. He thrust the knife into her—again and again and again—eventually sinking it into her neck and twisting. He left Gayle crumpled at the base of the steps and went back upstairs to wash himself in a bathroom. He grabbed a jacket to cover the blood on his shirt. He also nabbed Gayle’s purse along with an Apple laptop computer and stuffed those in his backpack. He walked out of the house, back to the bus stop, and rode to his Buick.

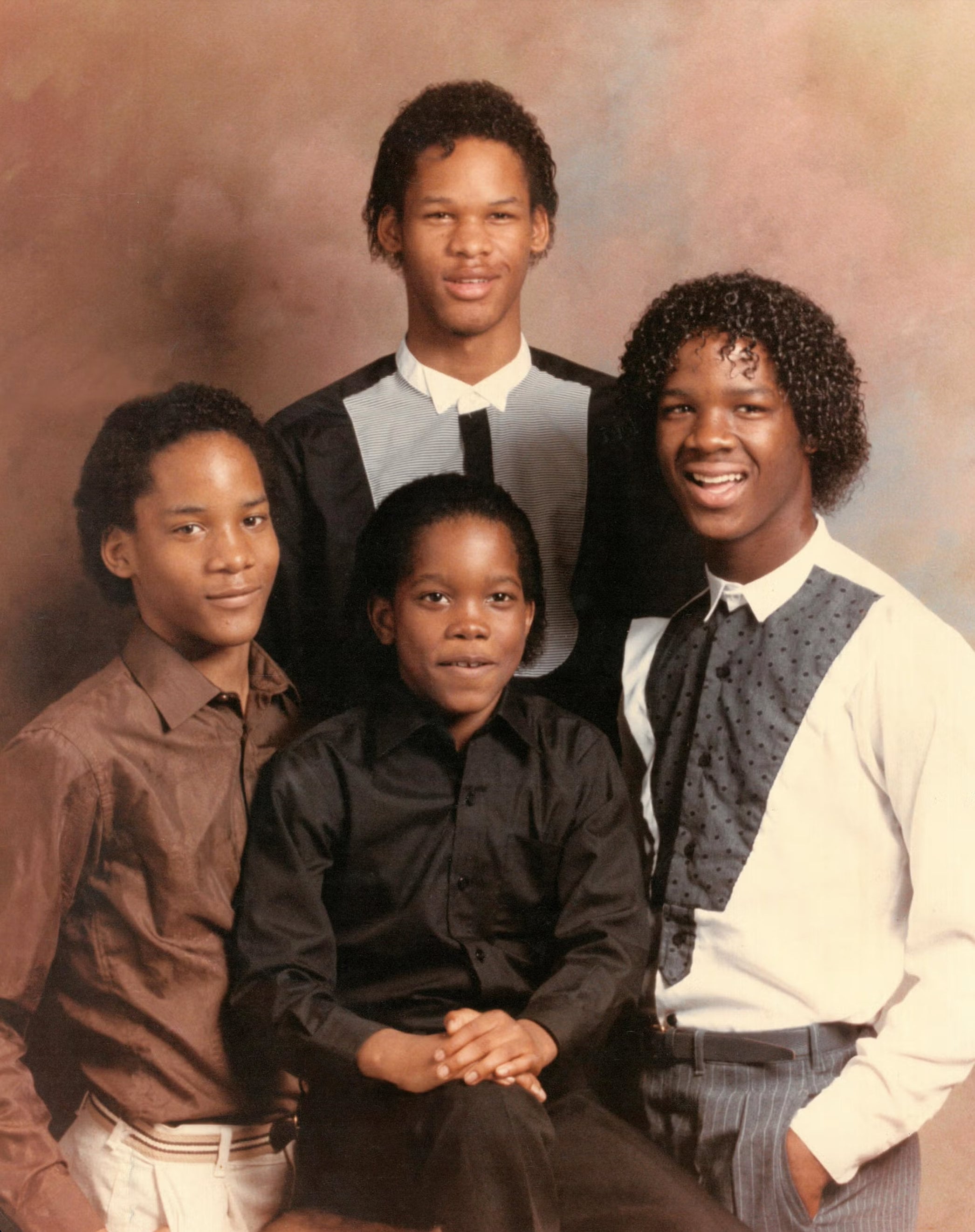

Williams, at left in the brown shirt, with his three brothers.

Williams then picked up his girlfriend, Laura Asaro, who thought it odd that he was wearing a jacket when the temperature was almost 90 degrees with high humidity. When he removed the jacket, she noted blood on his shirt and scratches on his neck. He said he’d been in a fight, she later told the authorities.

Williams and Asaro had been sleeping in the car while parked outside his grandfather’s house and kept their clothes in the trunk. The next day, Asaro found a purse in the trunk containing Gayle’s identification card. Thinking her boyfriend was cheating on her, Asaro demanded an explanation. He told her the purse belonged to a woman he’d killed after she surprised him while he was robbing her house. Then, Asaro later testified, he closed his hands around her throat and threatened to kill her if she told anyone.

When police eventually searched the Buick—some fifteen months after Gayle was murdered—they found in it a St. Louis Post-Dispatch ruler, a calculator, and a medical dictionary. With Asaro’s help, they also found Dr. Picus’s Apple laptop. She led the detectives to the house of Glenn Roberts down the street, where she said Marcellus had traded the computer for crack. Roberts testified at the trial that Marcellus had pawned the computer for cash. Either way, the laptop matched the serial number on the receipt Picus had given the police.

No forensic evidence linked Williams to the scene of Gayle’s murder. Not the bloody fingerprints police investigators collected. Not the stray hair samples. Not the shoe prints around the body. Not the DNA taken from under Gayle’s fingernails. And nothing on the murder weapon.

The strength of the prosecution’s case relied on the testimony of two witnesses—Asaro and Henry Cole. When police first asked her what she knew about the crime, Asaro was a thirty-one-year-old mother of six children who was doing sex work to fund her crack habit. Cole was a fifty-three-year-old drug addict with a history of psychosis and ratting out others. He had been convicted a dozen times of various crimes, ranging from stealing mail to robbery. Ten months after Gayle’s murder, Cole approached the police and told them Williams had confessed in detail how he’d killed the “newspaper lady” in University City. They’d been confined together in the St. Louis County workhouse, a medium-security penitentiary where indigent convicts worked to pay off their fines. After listening to Williams, Cole said he had surreptitiously scribbled notes, which he pulled out of his sock to show the police.

At the trial, Williams’s state-appointed attorney tried to discredit Cole’s and Asaro’s testimonies by claiming they were motivated by having charges against them dismissed and by reward money. Picus had put up $10,000 to help the police find his wife’s killer. Cole had demanded payment before giving his deposition, so the prosecutors encouraged Picus to pay Cole $5,000 in advance. The defense attorney also argued that the accounts of Asaro and Cole easily could have been gleaned from newspaper and television reports of the highly publicized case. The prosecutor countered that Cole and Asaro had known details not reported in the newspaper, such as the fact that the killer had twisted the knife and left it lodged in the victim’s neck, the location of her body in the house, and that a purse was missing. (Cole and Asaro have both since died.)

The twelve jurors deliberated for five hours. On June 15, 2001, they found Williams guilty of first-degree burglary, first-degree robbery, two counts of armed criminal action, and first-degree murder. The following week, they listened to victims of Williams’s previous crimes and to Lisha’s friends and mother. They also heard from Williams’s son and stepdaughter that he had encouraged them to work hard in school and stay out of trouble.

The prosecuting attorney, Keith Larner, brandished the bloody autopsy photos, played the 911 tape of Picus sobbing as he reported his wife’s murder, and—pointing to Williams—told jurors, “This man viciously and brutally and savagely killed Lisha Gayle in her home while she was alone.” Williams’s defense attorney, Joe Green, countered by asking jurors to decide impartially rather than emotionally, arguing that a sentence of life in prison was punishment enough. The jury took less than an hour and a half to decide Williams should be put to death. And thus sealed his fate.

time, his mother, Ella Louise Williams, was married to the father of her second son. Marcellus was the third of four boys she conceived with four different men. Throughout his childhood, she called Marcellus the “one mistake” she made in her life. Ella was not a warm or affectionate woman. She did not hug her four boys or tell them she loved them. When Marcellus misbehaved, she beat him or encouraged her boyfriends to beat him.

Marcellus’s father was a crack addict with a rap sheet. Young Marcellus yearned to know him, like his brothers knew their fathers. The first time they met, his father whipped him. Marcellus saw his father only two more times as a child.

Ella found occasional work cleaning houses and later as a maid, but it was never enough. When Marcellus saw his mother break down, sobbing because she couldn’t provide for her boys with her meager wages and the food stamps, he longed to relieve her despair. At seven, he thought maybe if he ran away, having one less mouth to feed would ease her suffering.

Eventually they moved in with her parents, who lived in a north St. Louis neighborhood plagued by unemployment, guns, drugs, and crime. One of his uncles sexually abused Marcellus when he was seven or eight years old. So did an aunt. When Marcellus turned to a church deacon for help, that man molested him as well.

Not surprisingly, Marcellus acted out at school. He fought with other children. Sassed teachers. Skipped school. Got suspended. Failed classes. Soon he was smoking weed, using angel dust, and popping Valium. By the second semester of tenth grade, failing all his classes, he dropped out. Overcome with guilt about letting his mother down, he thought about killing himself with pills. He was a sensitive, hurting, angry young man who would eventually be diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

That came from Donald Cross, a licensed psychologist hired by public defenders to evaluate Williams in 2003, when he was thirty-three years old. Cross concluded, “Mr. Williams was at risk for violent delinquent behavior at conception. . . . He simply did not have a chance to live a healthier and more functional life.”

Indeed, young Marcellus, busted seven times for various offenses, landed in the custody of the Division of Youth Services at age sixteen. Two years later, he was locked up for a burglary and then again—not long after his release—for stealing a car. When he got caught filching jewelry and electronic equipment worth more than $150 in two home burglaries within a span of five days in 1990, he was sentenced to seven years in prison, which he served from 1990 to 1997. At the time he was charged with Lisha Gayle’s murder, he was in the workhouse. Police had caught him running down the street on August 31, 1998, after he robbed a downtown St. Louis doughnut shop at gunpoint. Less than six weeks earlier, Williams, along with two other men, had robbed a Burger King where he had previously worked. Stealing had become a way of life for Williams, the cash, jewelry, and electronics paying for his drug habit.

During the early days of his incarceration, he was still an angry young man, acting out as he had in school. He was written up more than a hundred times for arguing with guards, refusing to obey orders, and talking back to those in authority. But he mellowed, quitting drugs, writing poetry, studying world religions in the prison library, and ultimately embracing the Muslim faith, going by the name Khaliifah. In 2014, he was chosen as the imam for his fellow prisoners at the Potosi Correctional Center, where Missouri houses its death-row inmates. “Marcellus would be the first to say he’s ashamed of his past,” says Tricia Rojo Bushnell, executive director of the Midwest Innocence Project, which has worked to free Williams since 2017. “That’s what we’ve seen is part of what makes him such a great spiritual leader for other folks. He understands all of us are capable of change and are more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”

In his role as imam at the Potosi facility, he ministered to fellow inmates on death row as well as the general population. Not long ago, he asked his attorneys for a book on sign language so he could learn to communicate with another Muslim inmate who was deaf. “That’s emblematic of how much love he had for his community,” says Adnan Sultan, a staff attorney with the Midwest Innocence Project and a fellow Muslim.

Ever since his conviction, Williams and a supporting cast of attorneys had filed appeals and petitions and motions arguing that he was wrongfully convicted and professing his innocence. They pointed to a slew of underlying factors and legal arguments, including confirmation bias, police-planted evidence, the unreliability of jailhouse snitches, racial discrimination during jury selection, and ineffective trial counsel.

The murder of a white woman during broad daylight in her suburban home three blocks from the police station sent shock waves through the community. Police soon ruled out Gayle’s husband, Dan Picus. For starters, he had no motive. Picus had not suspected his wife of cheating on him. “There’s absolutely no way she was having an affair or anything,” he told the police. “She was such an honest person, she wouldn’t do anything like that.” He didn’t stand to gain financially from her death, as he carried no life-insurance policy on her. And he had a firm alibi. The detectives confirmed through hospital logs and interviews with his colleagues that Picus had been working all day on August 11. He also passed a lie-detector test. The police had subsequently fingered a handful of suspects, a collection of rogues with rap sheets, but none of them panned out. Hair and blood samples they gave voluntarily didn’t match those found at the scene of the crime, and lie-detector tests they took reinforced the alibis they’d given to the detectives.

In January 1999, not long after Picus posted the $10,000 reward, the police got a call from a nineteen-year-old man who told them he knew two crackheads who had robbed a “news lady” in U City, and one of them had tried to sell him a laptop computer. The police followed the hot-laptop trail for months, through crack houses and condemned apartment buildings, talking to a dozen or more characters with varying degrees of credibility. Ultimately, they came up empty.

As the months passed without an arrest, the police worked under mounting pressure to solve the case, which remained in the news. The University City police chief fended off criticism for not calling on the area’s Major Case Squad—composed of nearly three dozen investigators from various local police departments—saying he had enough of his own officers working on the case. But by May, the burden fell upon two detectives, Paul Glickert and Dorothy Dunn, the latter of whom carried a photo of Lisha Gayle to remind her that there was still a killer at large. When Henry Cole called on June 4, 1999, the day he got released from the workhouse, they were eager to hear what he had to say.

Williams was an attractive suspect for the detectives, given his past. Dunn seemed convinced of his guilt from their first meeting, when she and another detective confronted him at the workhouse in November 1999 with a photo that showed the front of the house where Gayle was killed. “He froze and stared at the photo and made several attempts to swallow before being able to do so,” she wrote in her report. But Williams denied any knowledge of the crime and said he would not talk to them without an attorney present.

“I can see why they wanted to hang this on Marcellus, given his record, but none of those [previous] crimes are geographically from that area, none are at that level of violence involved,” says Larry Komp, chief of the Capital Habeas Unit of the Federal Public Defender for the Western District of Missouri. He and his staff had been working to free Williams since 2005, representing him in federal habeas petitions detailing violations of his constitutional rights in his conviction and sentencing. Says Komp: “It just never added up.”

But that’s the way it often goes with wrongful convictions, police seeking evidence that will confirm their theory rather than considering all possibilities. “We know from other wrongful convictions that a lot of people who were exonerated were picked up because police thought, They committed these other crimes, or I know him,and then they go down that tunnel vision of thinking that it must be him,” says Bushnell of the Midwest Innocence Project. “Then we miss finding the real perpetrators. We miss getting actual justice.”

One of those missed possibilities involved the case of Debra McClain. Nine days after Gayle’s murder, the county’s chief medical examiner contacted University City police to report striking similarities between the murder of Gayle and that of another woman, Debra McClain, who’d been killed three weeks earlier in a nearby suburb. Both were white women in their early forties (McClain was forty; Gayle was forty-two) with similar body types and long brown hair. Very little had been disturbed at the scene of either crime, though purses were missing from the two houses. Both women had been attacked during daylight in their own homes and stabbed to death with a knife taken from a kitchen drawer. They had both tried to defend themselves (evident from defensive wounds). What Mary Case, the chief medical examiner, found most improbable was that both women were discovered with the knife that killed them stuck in their bodies, a detail she called “extremely rare” in stabbing deaths.

Despite the similarities, the University City police detectives ultimately decided the two murders were not related. To date, no one has ever been charged in the murder of Debra McClain. This past year, in an effort to see if a connection could be found between the two murders, the St. Louis County prosecutor asked the St. Louis County police to reopen their investigation of McClain’s killing. A spokesperson for the St. Louis County police declined to comment, citing the fact that the case is still open. But the lack of a resolution suggests an ominous question: Could the person who killed both Gayle and McClain still be walking free?

Komp thinks the University City police abandoned the McClain case because they did not see it aiding the case they were building against Williams. If that were true, of course, it would raise serious doubts about the integrity of the case against Williams. “You don’t want investigative leads to be followed or not followed based on your fear that you’d do damage to the case you’re working up,” Komp says. “You’re building a case to find the right person, not the person you think it may be.”

And in building that case, some have suggested that the police may have gone so far as to manipulate evidence. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch ruler found in Williams’s car seemed to link him directly back to Gayle, a former reporter for the newspaper. Picus identified the ruler and calculator found in the glove box of the Buick as items that had been in his wife’s purse. Larner, the prosecuting attorney, told the jury that Williams had kept the ruler as a trophy. But defense attorneys argued in their appeals that the prosecutor had no way of proving Williams had actually placed those items in the car. By the time detectives found them—fifteen months after the fact—someone else, like Asaro, who had access to the car, could easily have placed them there.

So could the police. That’s what attorneys on Williams’s defense team believe might have happened, because the fingerprints on the medical dictionary were not Williams’s. Nor did the dictionary belong to Dr. Picus. “I think they collected some things and put them in the trunk,” Komp told me. “They probably thought it was going to be an easy connect to the crime scene, but Dr. Picus says, ‘No, none of my medical books or dictionaries are missing.’ ”

To be clear, there is no hard evidence to support the speculation by Williams’s attorneys that the police intentionally mishandled evidence or that they dropped the McClain case to avoid discovering anything that might complicate the case against Williams for Gayle’s murder. Detectives Dunn and Glickert have since retired. They did not respond to requests to talk about their investigation.

The legal team trying to save Williams has also highlighted the issue of conflicting accounts from Cole and Asaro. Both insisted that Williams had told them in detail what happened at 6946 Kingsbury the day that Gayle was murdered. Yet the accounts they gave police and offered as trial testimony clashed with each other’s, contradicted their own, and didn’t line up with evidence found at the crime scene.

Among the many examples detailed in Williams’s appeals, Asaro said Williams had cleaned off the knife after the murder, but it had been found in Gayle’s neck. Cole said Williams took the purse from upstairs, but her husband said Lisha kept it in the kitchen closet. Asaro said Williams drove to the house; Cole said he took the bus. Cole said Williams left the house through the front door, but Picus found the back door open. And so on.

Maybe time, drug use, and mental illness had messed with their memories of the specifics. They could still have been telling the truth that Williams had confessed to them. But given the stakes of the case, it’s important to consider that both Asaro and Cole fit the profile of unreliable, incentivized witnesses who receive something in exchange for telling the police and prosecutors what they want to hear. In Cole’s case, he asked for the reward money up front and would only give a deposition after receiving half.

When Asaro finally implicated Williams to police—after saying she had withheld what she knew twice before when they’d questioned her because Williams had threatened her—she feared they were going to arrest her on several outstanding bench warrants. But the police let those slide. Asaro’s knowledge that Glenn Roberts had the stolen computer could have implicated her, an incentive to pass the blame to Williams. His brother Jimmy Williams testified he had seen Asaro around that time with a laptop, and Roberts later swore in an affidavit that Williams had told him the computer belonged to Asaro, a detail the defense had not been able to present at the trial.

“None of the physical evidence supported the incentivized witnesses,” Komp says. “And there’s a reason for that: because they weren’t telling the truth.”

During the appeal process, two of Cole’s nephews provided affidavits detailing their uncle’s drug addiction, erratic behavior, and lying tendencies. “Everyone in the family knew that Henry made up the story about Marcellus committing the Felicia Gayle homicide,” Durwin Cole swore under oath. Meanwhile, the live-in boyfriend of Asaro’s mother, who’d known Asaro since she was a child, swore she was a police informant who had a pattern of lying to police to get herself out of trouble.

Jailhouse snitches and other incentivized witnesses like Cole and Asaro are a common cause of wrongful convictions. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 8 percent of all exonerees nationwide were convicted at least in part by testimony from jailhouse informants, with a higher incidence among more severe crimes.

Race also plays a factor in wrongful convictions. In “Sacred Victims: Fifty Years of Data on Victim Race and Sex as Predictors of Execution,” a paper published this year in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, the authors write, “If the victim was a white woman, the District Attorney was more likely to seek death, the jury was more likely to impose death, and the condemned defendant was more likely to be executed than if there was no white female victim.”

Years of research have shown that the death penalty is disproportionately applied. The ACLU reports that since 1976, people of color have accounted for 43 percent of all executions carried out in the U. S. And Blacks are convicted of murder and sentenced to death for crimes they didn’t commit far more often than whites. Data collected by the National Registry of Exonerations show that innocent Black people are about seven times as likely to be wrongly convicted of murder as innocent whites. According to the registry, “Many of the convictions of African-American murder exonerees were influenced by racial discrimination, from unconscious bias and institutional discrimination to explicit racism.”

Numerous studies have revealed this racial disparity in Oklahoma, Louisiana, Texas, California, Washington, and particularly in Missouri. Of the one hundred people executed in Missouri since 1989, thirty-nine were Black, though Black people constitute only 11 percent of the state’s population. A 2015 study found that in St. Louis County—where Williams was convicted and sentenced—a person convicted of murder is three times as likely to be executed as someone convicted of the same crime elsewhere in the state.

It’s easy to see how that played out in Williams’s case. Though 25 percent of the population of St. Louis County is Black, Williams was tried by a jury of eleven white people and one Black citizen. The county has a documented history of prosecutors striking Black potential jurors. In 1990, nine criminal-defense attorneys signed affidavits stating the county’s prosecutors “systematically excluded” Black jurors with their peremptory strikes. At Williams’s trial, Larner, the prosecuting attorney, used six of his nine peremptory strikes to exclude Black people. He would later say he struck one Black man because he and Williams “looked like they were brothers” and the man had the “same piercing eyes.”

The team representing Williams argued that Larner’s strikes of three Black potential jurors violated Williams’s constitutional rights with a Batson challenge, which stipulates that when it appears that race was the basis for a prosecutor’s dismissal of a juror, the prosecutor must explain a neutral reason for peremptory strikes. But over and over, various courts dismissed Williams’s challenges.

Williams’s attorneys also appealed his conviction and sentencing on the grounds that he had ineffective trial counsel that, among other deficiencies, failed to investigate and present evidence to raise questions about the testimonies of Cole and Asaro, and did not invoke details of Williams’s troubled childhood that could have elicited sympathy sufficient to mitigate the jury’s death-sentence decision. Indeed, the defense counsel, Joe Green, later said that such testimony “could have saved Marcellus’s life.” He said he simply didn’t have the time necessary to prepare an adequate defense because he was busy representing another man who had killed his wife in a courthouse shooting. Green would later admit, “I don’t believe [Williams] got our best.”

As his defense team pursued its appeals over the years, Williams’s path toward execution took on a stop-start pattern familiar in capital cases. The Missouri Supreme Court stayed Williams’s initial execution, scheduled for June 6, 2003, so he could seek collateral review in Missouri and federal courts. Once those avenues proved unsuccessful, it set another execution date for January 28, 2015. Then, six days before Williams was scheduled to die, the state supreme court granted another stay pending the results of additional DNA testing on the murder weapon using methods not available at the time of his 2001 trial. Three experts concurred that the results of the tests, while unable to identify the actual killer, were sufficient to rule out the presence of Williams’s DNA on the butcher knife used to kill Gayle. The special master appointed to oversee the testing sent the case back to the Missouri Supreme Court, yet without a hearing on the results, it set a new execution date for August 22, 2017.

Four different courts, including the U. S. Supreme Court, denied Williams’s various attempts to put off his death in 2017. Then the Midwest Innocence Project prevailed upon the governor of Missouri to appoint an independent board of inquiry to review the DNA findings. Less than five hours before Williams’s scheduled execution by lethal injection, Governor Eric Greitens halted the execution and convened a board of inquiry, composed of five retired Missouri judges, to “consider all evidence presented to the jury, in addition to newly discovered DNA evidence and any other relevant evidence not available to the jury.”

Nearly six years passed without a formal report. Greitens’s successor, Governor Mike Parson, dissolved the board on June 29, 2023, saying it was time to move on. “We could stall and delay for another six years, deferring justice, leaving a victim’s family in limbo, and solving nothing,” Parson said in a statement.

Williams expressed his frustration with the legal process in a poem he wrote in 2019 titled “Exoneration over Mitigation”:

while the rusty scales of justice are overburdened with hypocrisy, exclusionism and secular weight,

now who cares to care despite being unable to fully relate?

try to look through bright brown eyes or visualize the death warrant and execution date,

as lawyers scramble to litigate—

for their clients in decline or in a defiant state,

so obvious what i’m implying still they offer up pills to sedate,

as for me i offer my will and complete trust in The Best to create,

and i lend my voice to say:

EXONERATE!

After Parson disbanded the board of inquiry, Williams sued the governor, claiming that dissolving the board before it issued a report violated the law and his constitutional rights. A Cole County civil judge denied Parson’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, so the governor turned to the Missouri Supreme Court, which dismissed the lawsuit, allowing the execution to proceed.

Then Williams suddenly gained a powerful new ally named Wesley Bell. The former public defender and prosecutor had made a name for himself during the 2014 protests in Ferguson after a white police officer fatally shot an unarmed Black teenager, Michael Brown. In 2018, Bell challenged longtime St. Louis County chief prosecutor Bob McCulloch for office. McCulloch’s twenty-eight-year tenure had been tainted by charges of racism. The Missouri Supreme Court reversed two death-penalty cases secured by McCulloch’s office after Williams’s trial because of “racially discriminatory strikes” of Black prospective jurors. And the state’s intermediate appellate courts also reversed a number of McCulloch’s convictions on the same grounds. The contest between Bell, a Black man, and McCulloch, who is white, was seen as a referendum on racial justice and criminal-justice reform. Bell, who ran on a platform opposing capital punishment—calling it racially biased—prevailed to become the county’s first Black chief prosecutor.

In January 2024, Bell went to bat for Marcellus Williams and took the unusual step of petitioning the Circuit Court of St. Louis County to reverse a conviction his own office had secured. Bell asserted that mistakes made by his predecessor’s team and DNA testing of the murder weapon, “when paired with the relative paucity of other, credible evidence supporting guilt, as well as additional considerations of ineffective assistance of counsel and racial discrimination in jury selection, casts inexorable doubt on Mr. Williams’s conviction and sentence.” He also requested an evidentiary hearing to consider new findings that could prove Williams’s innocence. The circuit court agreed to hold one on August 21, 2024.

The plan was to present results that new testing of DNA found on the murder weapon belonged to someone other than Williams, presumably the true killer. But two days before the scheduled hearing, that strategy was undermined by the lab report showing the DNA on the knife belonged to Larner, the prosecutor, and an investigator from his office, both of whom had handled the murder weapon at a time when protocols for protecting the integrity of evidence were not as stringent as today’s. The contaminated evidence delivered a knockout punch to Williams’s latest claim of innocence. The DNA on the murder weapon might not implicate Williams, but it didn’t clear him, either.

With only thirty-six days until his scheduled execution, Williams’s team scrambled to find another means to spare his life. They struck upon an Alford plea, which allowed Williams to plead no contest. Rather than admitting guilt, he simply acknowledged that there was enough evidence for a jury to convict him of the crime. He also waived his right to further appeal his case unless new evidence was discovered (which was still a possibility if, for instance, Debra McClain’s killer could be found and implicated in Gayle’s murder). As part of the plea, the death penalty would be vacated, and Williams would spend the rest of his life in prison without parole. In lieu of the evidentiary hearing, they presented this proposal to the circuit court.

The deal seemed like a satisfactory arrangement for everyone. Picus, who believed Williams had killed his wife but opposed the death penalty, was in favor. So were attorneys from the Innocence Project, the federal public defender’s office, and the prosecutor’s office, which had brokered the deal. “The court finds the consent judgment is a proper remedy in this case,” concluded the presiding judge, Bruce Hilton.

But it ran into opposition from Andrew Bailey, the Missouri attorney general. Bailey had previously fought to uphold the convictions of three other Black men who’d been accused and convicted of murder before ultimately being exonerated—Kevin Strickland, Lamar Johnson, and Christopher Dunn. Now Bailey asked the Missouri Supreme Court to block the Alford plea, and it did the next day. The circuit court set aside the plea agreement and scheduled an evidentiary hearing for August 28. One day Williams thought his life had been spared, and the next he was back on death row.

At the August 28 hearing, absent the expected DNA findings on the murder weapon, attorneys from Bell’s office doubled down on the arguments of ineffective counsel, racial bias in jury selection, and the unreliable testimony of incentivized witnesses. They also argued that the prosecutors had handled (in the case of the knife) or destroyed (fingerprints from the crime scene) evidence in bad faith.

In his ruling two weeks later, Judge Hilton found that the prosecutors had not acted in bad faith, that Williams’s attorneys had failed to provide “clear and convincing” proof of his innocence, and that the “remaining evidence amounts to nothing more than re-packaged arguments.” Since every claim of error Williams made had previously been rejected by other Missouri courts, Hilton concluded he had no basis to find Williams innocent and denied the motion to vacate or set aside his conviction and sentence.

Bushnell of the Midwest Innocence Project says it is “heartbreaking to see the system so broken” and that the decision shook people’s fundamental belief in how our legal system should work. “It’s such a great example of our court system’s obsession with finality over fairness,” she says.

With only twelve days until September 24, the decision sent Bushnell and other attorneys at the Midwest Innocence Project, Bell’s office, and the federal defender’s office into overdrive, working late nights and weekends to stop the execution. On Tuesday, September 17, they asked the U. S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri to reconsider its 2010 denial of the unconstitutional removal of Black prospective jurors based on new evidence: Larner’s admission at the August 28 hearing—the first time he’d had to justify himself under oath—that “part of the reason” was one prospective juror’s “familial” resemblance to Williams. U. S. District Judge Rodney Sippel denied their motion.

On Wednesday, September 18, Williams’s attorneys asked the U. S. Supreme Court to review Parson’s dissolution of the board of inquiry, an action they claimed had denied Williams’s right to due process. They also requested a stay of the execution until SCOTUS had resolved the case of Richard Glossip, a white man on death row in Oklahoma in a similar case where the state court had spurned the state’s confession of error. The nation’s highest court would hear Glossip’s case in October.

On Saturday, September 21, Williams’s attorneys filed a brief asking the Missouri Supreme Court to send the case back to the circuit court for a more comprehensive hearing, claiming the court erred in its rulings and arguing Larner’s admission of race-based peremptory strikes did warrant vacating Williams’s conviction and that the contamination of evidence violated his due-process rights.

They also submitted a petition to the governor making the case for him to grant clemency. It was what the family wanted. It was even what some of the jurors who had convicted Williams now wanted: “As several jurors currently attest, the case and the evidence now bear little semblance to the case they heard in 2001.” And in a personal plea, Komp added that Williams was a changed person, now a pious man of faith and a beacon to others: “The Marcellus Williams of today brings care, love, and guidance to those whose lives he touches.”

While Williams’s attorneys believed in the righteousness of their cause, they knew these last-ditch efforts were a long shot, especially the ask for clemency. Parson, a former sheriff serving out his last months as governor, was a staunch law-and-order conservative. He had pardoned Patricia and Mark McCloskey, who’d pointed a handgun and an AR-15 rifle, respectively, at unarmed Black Lives Matter protesters walking by their St. Louis home in 2020, after they pleaded guilty to misdemeanor harassment (Patricia) and fourth-degree assault (Mark). But he’d refused to pardon two Black men, Kevin Strickland and Lamar Johnson, before they were eventually exonerated and released from prison.

Monday morning, around 9:00, the guards came for Marcellus and they made the twenty-minute drive from death row in Potosi to the execution site in Bonne Terre, a hardscrabble town of almost seven thousand in southeastern Missouri. Around the time they were on the road, the Missouri Supreme Court listened to oral arguments. The state’s highest court decided not to intervene or postpone the execution, scheduled for the following day.

In the late afternoon, Parson rejected the clemency request. His office issued a lengthy statement reiterating arguments of Williams’s guilt and saying, “Nothing from the real facts of this case have led me to believe in Mr. Williams’s innocence, as such, Mr. Williams’s punishment will be carried out as ordered by the Supreme Court.”

Wesley Bell promptly responded with his own statement: “Even for those who disagree on the death penalty, when there is a shadow of a doubt of any defendant’s guilt, the irreversible punishment of execution should not be an option.”

He expanded on that theme in a subsequent conversation with me. “When we cannot say with certainty that a defendant is guilty and that defendant is executed—a punishment that can’t be undone—that is the system failing,” Bell told me. “When I can’t look a victim’s family in the eye and tell them the right person was punished, that’s problematic as a prosecutor or just a moral person.”

By Tuesday, September 24, the day scheduled for Williams’s execution, his last hope of reprieve lay with the U. S. Supreme Court. Williams’s case had received considerable national attention in the media. It was one of five executions to be carried out in a week’s time nationwide and would be Missouri’s one hundredth since 1989. More than a million people had signed online petitions posted by Change.org, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, and the Innocence Project demanding Williams not be put to death. On Monday, Virgin Group founder Richard Branson had placed a full-page ad in The Kansas City Star calling on Parson to stop “a devastating miscarriage of justice” and urging people to contact the governor. Others opposed to Williams’s death sentence protested outside the courthouse in St. Louis and prayed on a street corner in downtown Kansas City.

In the late afternoon, about an hour before the execution, scheduled for 6:00 p.m., demonstrators began to gather at the Eastern facility in an area cordoned off by concrete blocks and watched by armed Department of Corrections guards. Nearly a hundred people assembled, including forty-three bused down from St. Louis by the archdiocese. Some wore T-shirts that said, stop executions now, execute justice not people, and death ≠ justice. One held a sign that said, what if we got it wrong?

“It’s like we’re in a race with Oklahoma and Texas to kill as many people as we can,” one of the demonstrators, Father Mitch Doyen, told me. “This one is especially heartbreaking. I’m not convinced of Marcellus Williams’s innocence, but there’s enough doubt that the man should not be executed.”

That day Williams spent hours talking on the phone in his cell with his son Marcellus Jr. At 10:53 a.m., he began to eat his last meal, which included chicken wings and tater tots. He met with his spiritual advisor, Imam Jalahii Kacem, from 11:01 a.m. to 12:32 p.m. Three days earlier, Williams had handwritten his last statement on a form provided by the Department of Corrections: “All Praise Be To Allah In Every Situation!!!”

Williams was not one to show much emotion, but Marcellus Jr. could tell his father’s faith had allowed him to accept his pending death. “He was at peace leaving this world for the next, because he knew his soul would move on,” Marcellus Jr. told me.

A little before 5:00 p.m., Williams’s attorneys got word that the U. S. Supreme Court’s three left-leaning justices said they would be willing to grant his stay of execution, but they were outvoted by their six conservative peers. Komp called Williams with the news. He said he was sorry, told him how much Williams meant to him and the rest of the team. Williams expressed his gratitude and said he was going to start his final prayers.

At her home, shortly after getting the word, Bushnell of the Midwest Innocence Project went live on a remote interview with CNN’s Jake Tapper. “Tonight Missouri will execute an innocent man,” she said, her voice cracking slightly. “And they will do it even though the prosecutor doesn’t want him to be executed, the jurors who sentenced him to death don’t want him to be executed, and the victims themselves don’t want him to be executed. That is what will be the state of justice tonight in Missouri.”

When she finished, exhaustion and grief overwhelmed her. She sat on the steps and cried.

At 6:00 p.m., Marcellus lay on a gurney in the state’s execution chamber, a stark room in the bowels of the Eastern facility with whitewashed cinder-block walls, mirrored windows, and a black door in one corner. Bailey, the attorney general, notified DOC officials that there were no more outstanding legal impediments, and Parson gave word to proceed. At 6:01, an anonymous execution team began the flow of a lethal dose of the barbiturate pentobarbital into one of Williams’s veins. Then guards opened the dark-blue curtains to the viewing areas on three sides of the chamber.

Three journalists, four DOC officials, a woman from the attorney general’s office, and a prison guard occupied one. Marcellus Jr., Larry Komp, and Adnan Sultan of the Midwest Innocence Project sat in the viewing area opposite. The area reserved for members of the victim’s family remained empty. All was quiet. The attendees saw Williams lying on the gurney, a white sheet pulled up to his chin. Kacem, his imam, wearing a white cap, sat by his side.

Williams looked over at his son and gave him a little nod, as though to ask, You okay?

Marcellus Jr. nodded back. Yeah, I’m okay.

Williams made eye contact with Komp, who tapped his chest.

He exchanged a few words with Kacem, then closed his eyes. His mouth went slack.

As the lethal drug made its way through his body, his feet jiggled slightly under the sheet. His chest heaved several times. His body went still.

Kacem bowed his head, removed his glasses, and wiped tears from his eyes.

“My dad had his right hand on his left,” Marcellus Jr. told me later. “He closed his eyes, and after a few minutes, his hands dropped off the table, and that’s how I knew he was dead.” His voice thickened with emotion. “At the time, I didn’t cry. I just looked at my dad like he was asleep, but that was the last moment I had with him.”

The dark-blue curtains closed briefly. The witnesses in the two viewing rooms sat in solemn silence. Presumably, someone from the execution team entered the execution chamber to check Williams’s vital signs. When the curtains opened again, the imam was gone. Williams’s body lay alone on the gurney under the white sheet and the fluorescent lights overhead. Someone from the Department of Corrections intoned, “The execution of Marcellus Williams has concluded. Time of death was 6:10 p.m.”

And the dark-blue curtains closed.